A Long Pilgrimage of the Heart

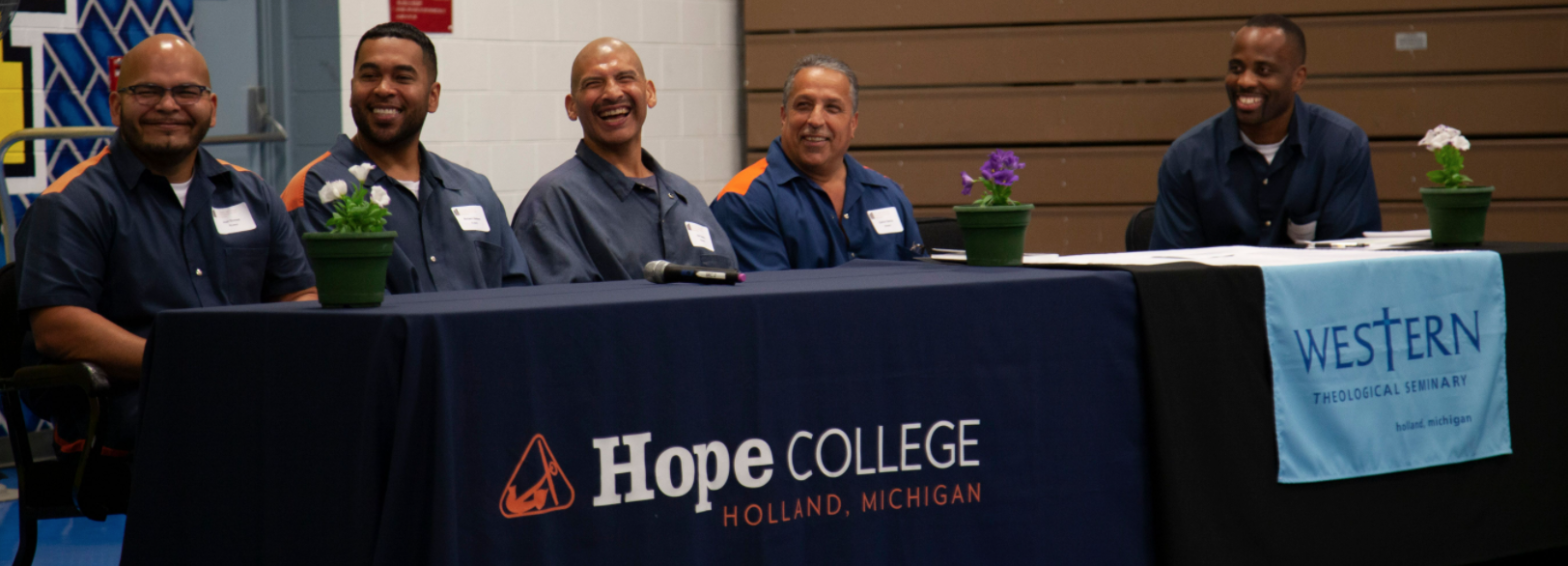

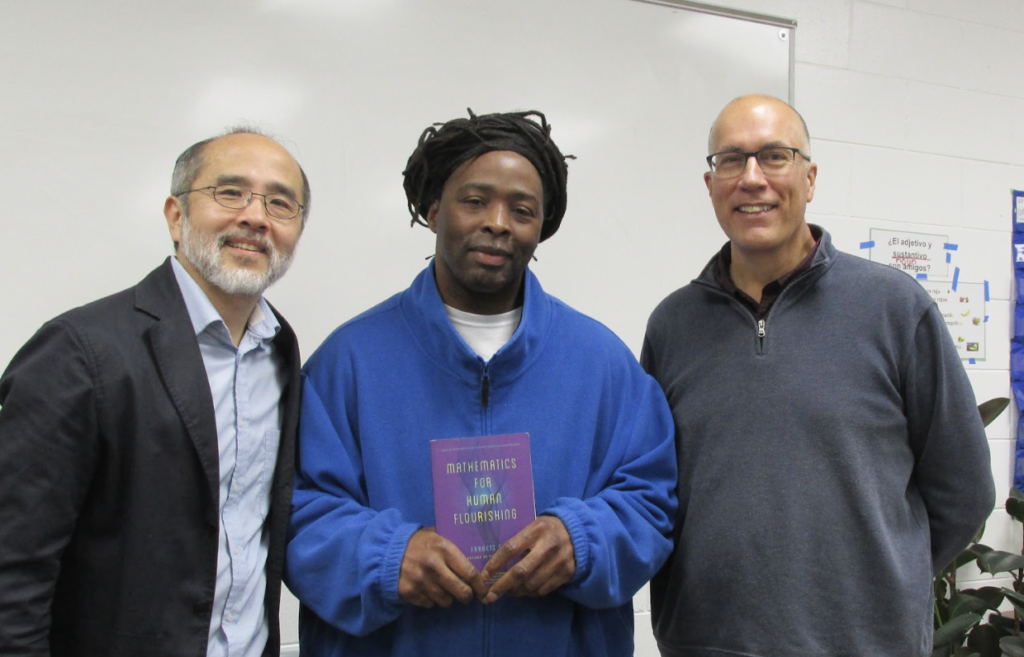

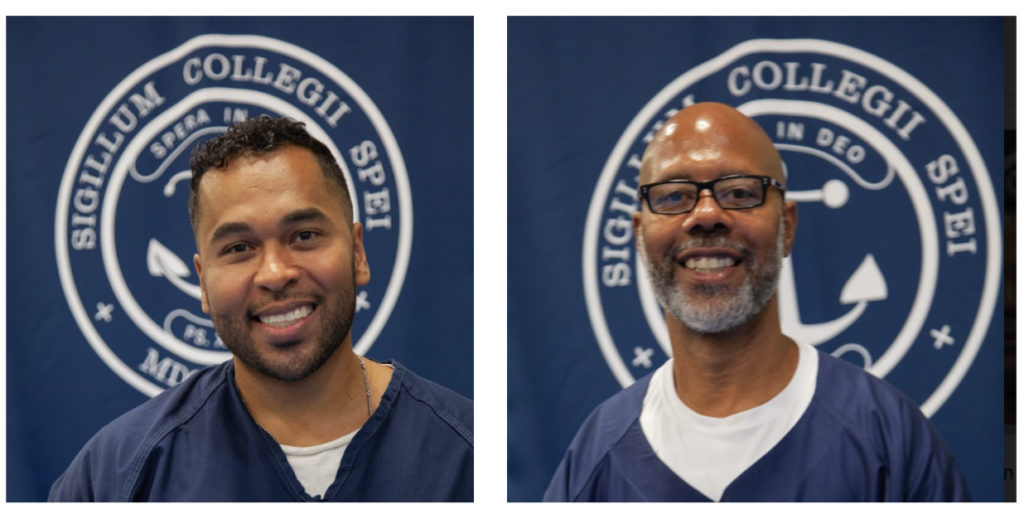

(Note: What follows is the text of an address made by Hope-Western Prison Education Program Co-Director Richard Ray at a Friends of HWPEP event at Muskegon Correctional Facility on June 11, 2024.)

Many sincere thanks for all of the very kind remarks. Every single one of them has touched my heart and will linger there for a long time. I’m grateful for each of you.

This is my last chance to stand at a podium before I retire, and I’d like to direct what few words remain to the students gathered here.

People labor under the understandable but incorrect view that we — my beloved colleagues and me — are bringing something of value to you. The truth of the thing is that it is you who are:

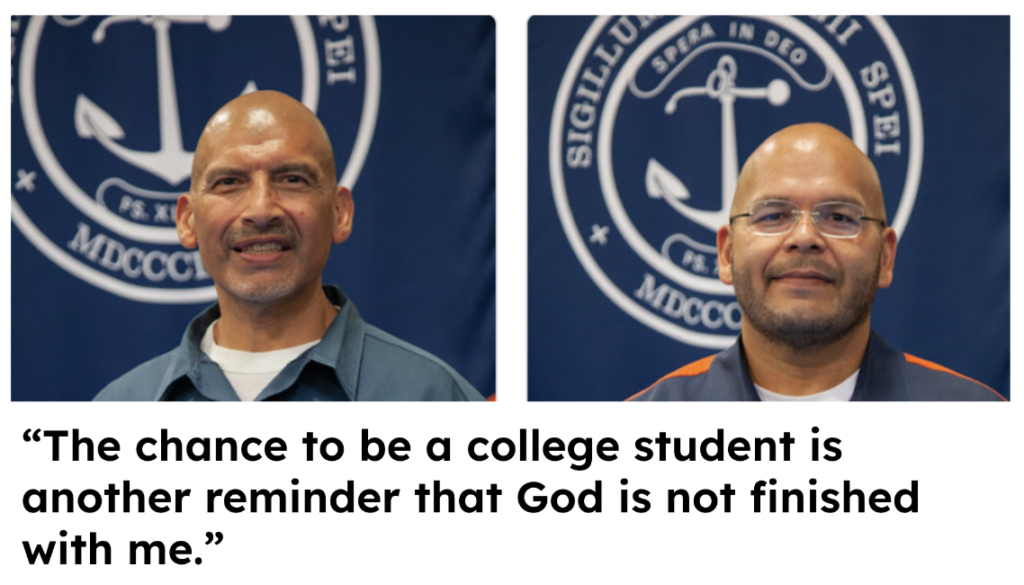

The truth of the thing is that you are the bringers and we are the receivers. Thank you for pouring so lavishly into our lives. We are grateful for each one of you. Each one.

I leave you today with a single question. It’s a question I hope you won’t try to answer too quickly. I hope that you’ll allow the question to ferment in your minds, and that you’ll return to it often — like a habit — even after a long pilgrimage of the heart during which you think you’ve finally arrived at an answer. The answering and re-answering of this question is the work of a lifetime.

And the question is this: What do you want? A seemingly simple question. You’re already formulating an answer, perhaps. Even now, right where you sit. Slow down. Your education — indeed, your entire life — is a project of discerning and shaping yourself to your fundamental desire, your sense of the ultimate good. In Latin, the summum bonum. Think about your life before your college education began. How might your life during those years have been ordered to the acquisition of money and power, safety and comfort? These desires — to the degree they might apply to your life — bring you into nearly perfect alignment with the vast majority of modern people, including all of us who possess the liberty to go home at the conclusion of today’s gathering. In this way, we share much. To be human is to want something.

Another way to ask the question is what do you love? To what is your heart ultimately yoked? St. Augustine names the heart as the organ of our desires. To love something is to desire it above all other things. And if you think you can love more than one thing — if more than one thing can be your summum bonum — well, that is an illusion. Choose carefully.

A third way of framing the question: What do you worship? Want, desire, love, worship — they’re all different words that point us to the thing above which no other thing exists. What is it for you? To what thing will your life serve as an altar? And in worship of what will you lay all you have before that altar?

“What do you want, desire, love, worship?”

Can you see why I’m discouraging you from a quick decision? This is the most important decision you’ll make in the short span of your lives. And it matters the most. It is an ultimate question. And your answer is an ultimate answer.

People will know what you want, love, desire, and worship by the fruit your lives bear. By what you say — yes — by more by what you do, and by how you live. Will you know it for yourself? Or, paraphrasing St. Augustine1 again, will you:

“. . . wonder at the heights of mountains, at the huge waves of the sea, at the long courses of the rivers, at the vast compass of the ocean, at the circular motions of the stars, and pass by yourselves without wondering.”

Your college education will help you — should help you — make a choice about your summum bonum. It should point you to what is True, Good, and Beautiful. And once you discover it, your life, and this world will never be the same again. Don’t settle for a summun bonum that anyone can take away from you.

In just a moment I’ll finally — finally, after six long years for some of you — be quiet, and I’ll ask Kary Bosma to come forward to greet you as I retire and she takes up her new role as Professor Stubbs’ partner in carrying forward the mission of HWPEP. Kary Bosma is a person of the highest character, and the most excellent moral vision. She is a person of longstanding leadership in the college-in-prison movement. She is utterly trustworthy, and completely reliable. She is another source of evidence for why HWPEP is a rightly ordered source of hope — both for you as people and as students and for the world that we inhabit together.

Finally, receive these words as a benediction from 20th Century British-American poet, W. H. Auden. These are words of encouragement and words of blessing, and the motto for my life:

“Stagger onward rejoicing … And may the Ancient of Days provide for all you must do His invisible guidance, Lifting up upon you the light of His countenance.”

__________

- Augustine, of Hippo, Saint, 354-430. The Confessions of Saint Augustine. Mount Vernon :Peter Pauper Press. ↩︎