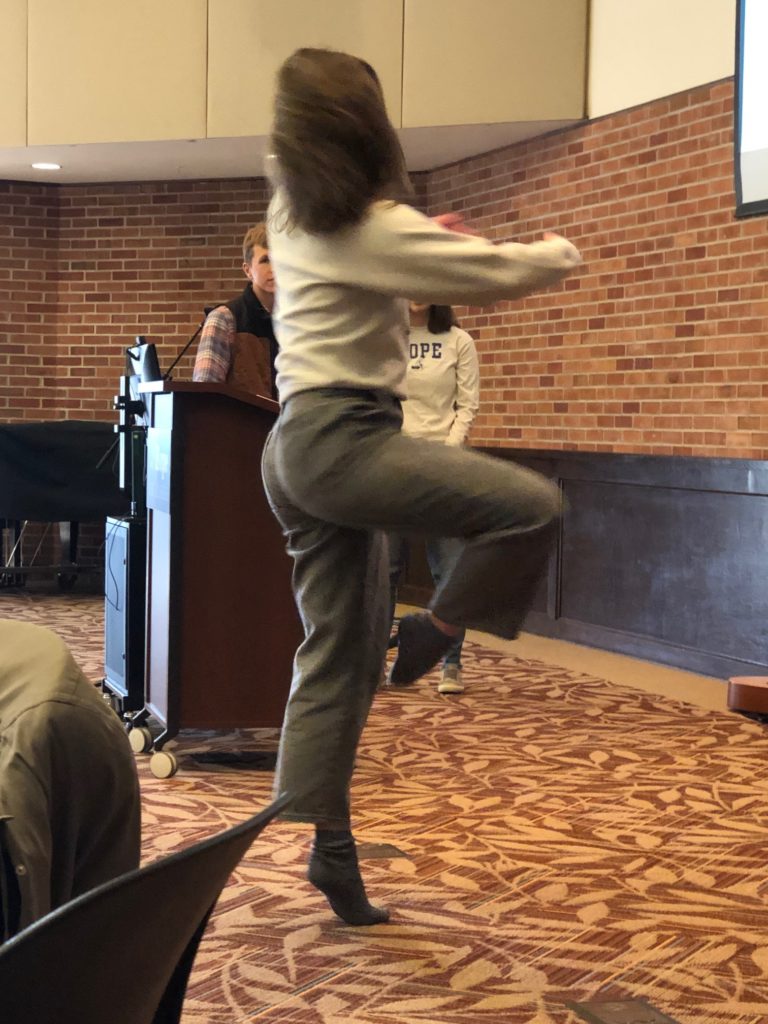

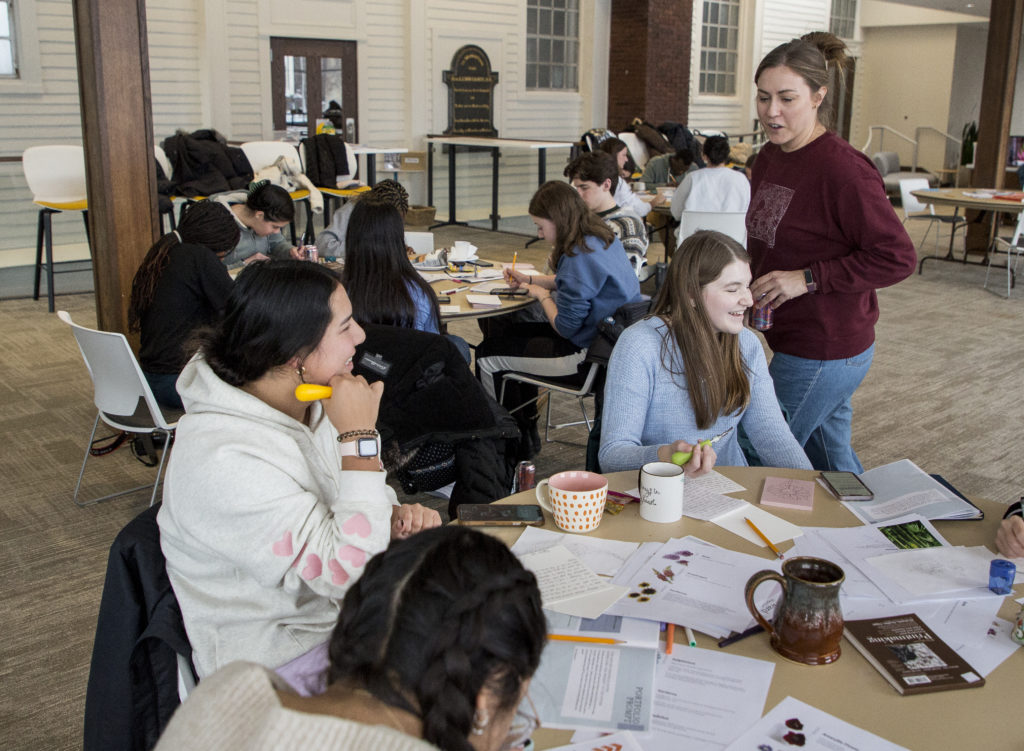

Jumping up from his seat, a student works out a theory on the whiteboard to better understand a concept in Dr. Griffin’s neuroscience class. He draws connections between the reading from the text, his personal faith and prior lessons. The students, fully engaged, nod in agreement with follow-up questions flowing. Similarly, in Dr. Andre’s pottery class down the hall, students are just as focused, attentive and engaged as they create new pieces of work that represent treasured experiences. As the classes come to a close, the students request additional reading material and express excitement for their homework. You may read this and think we’re making this up. What student asks for more homework? But we’ve been told that what we experienced in the Hope Western Prison Education Program (HWPEP) is par for the course among these three cohorts of students at the Muskegon Correctional Facility. These men demonstrate a palpable passion for learning and a drive to succeed that is nothing short of inspiring.

Contrary to what some may believe, the men at Muskegon Correctional Facility are more similar to their peers at Hope College than different. Both sets of students love learning and take their education seriously. And, they are eager to use their education to bless their communities by living into our mission at Hope College—to live lives of leadership and service. Additionally, both groups of students participate in visionary programs—Hope Forward and HWPEP—which focus on innovation in higher education through access, community and generosity.

As the Hope Forward program director and program coordinator, we have a front-row seat to the transformative impact that Hope Forward is having on undergraduate students at Hope College. Last week, we also witnessed firsthand the profound effect that HWPEP is having on students within the Muskegon Correctional Facility.

Hope Forward and HWPEP both offer a glimpse into educational transformation. With Hope Forward, students receive fully funded tuition provided by the generosity of donors and commit to give back after they graduate at any amount they choose so others have the same opportunity. Meanwhile, HWPEP provides incarcerated students a transformational education, rigorous academic opportunities, and a sense of belonging and purpose, made possible through the generosity of program donors. Both exemplify Hope College’s dedication to education, leadership and community impact, underscoring the transformative power of education across diverse contexts.

However, just as we can discuss the transformational experience of Hope Forward and HWPEP students, we must also acknowledge the ways in which these students are mutually transforming Hope College. To start, both programs challenge conventional notions of educational privilege and access, driving the institution to enhance equitable opportunities for all students. Furthermore, students infuse the institutional culture with a dynamic energy by enriching their own lives with purpose and living that purpose out during their time as students. As a result, they serve as living testaments and teachers of the transformative power of hope (both the concept and the place), leaving an indelible mark on the fabric and function of Hope College.

When we shared the principles of the Hope Forward program with the HWPEP cohorts, we were deeply moved by their response. The first question both groups asked was, “How can we give to Hope Forward?” Though an initial reaction may be to feel hesitant about receiving generosity from someone in these circumstances, fostering a culture of generosity is a core goal of Hope Forward. This simple question that was asked two times in a row struck a chord with us—here were individuals eager to give back and make a positive impact within their current circumstances. This shared commitment to generosity enriches the entire community, demonstrating that everyone, regardless of their situation, can contribute to and benefit from a culture of giving.

As we drove home with HWPEP Coordinator Amy Piscer, all three of us pondered a common question regarding our respective pilot programs: Are they working? With both programs set to graduate their first cohorts of seniors next spring, it’s a question that naturally arises. Amy shared insights from HWPEP’s leadership, who view the program as planting seeds that they hope will continue to flourish beyond the participants’ time in the program. Similarly, in Hope Forward, we find ourselves uncertain about what lies ahead for our inaugural cohort of students once they embark on their post-college journeys.

One obvious distinction between the two programs is the destination of their graduates: Hope Forward graduates will venture into various sectors of public life, while HWPEP graduates will re-enter different environments within the system. Some of the men will stay at the Muskegon Correctional Facility, some are up for parole, and some will return to correctional facilities outside their current context. No matter their trajectory, many of the men are excited to make a positive impact following the program. For instance, one HWPEP student who is up for parole wants to get a master’s of social work to help young men break free from cycles of familial turmoil, while another wants to start a writing program at whichever facility he’s in next. Some want to stay at MCF to help mentor future students in the program. Their excitement to leverage their Hope College education to bring hope to the world mirrors the anticipation we see in our Hope Forward students. Despite the unique paths our students in both programs may take, we share a common optimism that the transformational education and experiences provided by Hope College through HWPEP and Hope Forward will empower our students to lead lives of positive impact, wherever their futures may lead them.

The visit left a profound impression on us, igniting our eagerness to explore additional ways to support and learn from HWPEP. As of right now, both programs envision a meaningful exchange between our senior cohorts, where they will have space to reflect on their Hope College experiences using the same sets of questions, articulate their aspirations for positive impact in light of their transformational Hope College experiences, and hear from one another in the process. We firmly believe that both senior cohorts—Hope Forward and HWPEP—have much to offer each other, and we eagerly anticipate witnessing the transformation they will bring to one another, to Hope College and beyond.