For most of 2020, I’d been able to hold it together, rolling with every punch and willing myself to stay positive as each month took more and more of the life I once called “normal.” Sometime in March, the pandemic came to America and bizarre became the status quo. Right around that time, as we learned more about how the virus was especially dangerous for people of a certain age, or those with compromised immune systems, I started paying more attention to the progress of Congressman John Lewis in his fight against pancreatic cancer.

Selfishly, I prayed for him to stay clear of the virus and keep his light shining to guide us through the cataclysmic chaos that had become the nation’s de facto response to COVID. Still, I knew nothing would keep him from the 55th Anniversary of “Bloody Sunday,” commemorating the debacle that happened on March 7, 1965. On that day, just slightly more than a half-century earlier, Lewis and civil rights marchers had been clubbed and beaten by local law enforcement for daring to insist upon their right to vote. Lewis suffered a fractured skull, the first of what became many injuries he’d sustain for rejecting the second-class citizenship others had been trying to impose upon him.

As someone raised by parents, both from Montgomery, Alabama, and who matured into adulthood in the faded afterglow of the Civil Rights movement, I’d feasted on stories of the exploits of people like Rosa Parks, E.D. Nixon, Daisy Bates, Constance Baker Motley, Martin Luther King, Jr., Fred Shuttlesworth, and, of course, John Lewis. The blood spilled and lives lost from the harassment and abuse they’d suffered had literally transformed America into a somewhat less lethal nation for black people. But by March 8, 2020, something had happened, and was happening, to the transformation that Lewis and his contemporaries had given everything to achieve. He spoke of it in a CNN interview, sounding not tired but weary. Very weary.

The reporter said, “In your remarks, you talked about the importance of voting. You said, ‘Vote like you’ve never voted before.’ What did you mean by that?”[1]

Lewis: “I simply meant that we have the power to change things, and the vote is the most powerful non-violent instrument or tool we have in a democratic society and we must use it. If we fail to use it, we will lose it.”[2]

That was classic Lewis. A true believer in the untapped merits and virtues of America’s republican democracy, and certain that change was best achieved through non-violence, Lewis reaffirmed that the power citizens have to effect change lies in their vote. The son of sharecroppers, he’d seen and felt the violence those in power could wield when voters blessed them with the authority to inflict their cruelty. As such, voting wasn’t just a statement of who should be elected to a certain office but an inventory of a society’s moral strength or weakness; its commitment to fairness and justice; its extension of republican-democratic citizenship to all instead of the privileged few.

There was also the sober warning of “use it, or lose it.” Lewis had lived to see and suffer the possibilities of what the powerful were willing to do in suppressing the vote. He did not take for granted that those same elements were hard at work in the 21st Century and, because of them, democracy and democratic freedoms could never be assumed a perpetual certainty.

Continuing the interview, the reporter said: “You also spoke about redeeming ‘the soul of America.’ What does that look like?”[3]

Lewis: “We have to make America better for all of her people, where no one is left out or left behind because of their race or their color, or because of where they grew up or where they were born. We are one people. We are one family. We all live in the same house. That’s the American house.”[4]

He was eighty years old. The year was 2020. America was marching into the third decade of the 21st Century and the forces that still sought to not make America better for all of her people, and meant to leave certain people out because of their race or color, or because of where they grew up, or where they were born; the forces that rejected John Lewis’ notion of America being one people, one family, living in the same house, the American house, they had resurfaced and were running out the clock on his life.

I quaked with rage as I reflected upon the fact that, here he was nearing the end, and John Lewis was fighting an updated version of the same battle he’d been waging all his life. The lines of conflict had been drawn long before his birth with 1903 being a watershed due to the publication of The Souls of Black Folk. Written by the brilliant sociologist, historian, and civil rights activist, W.E.B. [William Edward Burghardt] DuBois, it predicted that for the United States of America, the “problem of the twentieth century” would be “the problem of the color-line.”[5]

By the time of Lewis’ birth, on February 21, 1940, bigots could take immense pride in knowing that Jim Crow’s cancerous racism had reduced African Americans to a level of second-class citizenship far exceeding Dubois’ somber pronouncement. Shaped by a society that for nearly four-hundred-years, had found ever creative ways of denying blacks their humanity and freedom, there was little reason for Georgia-born John Lewis (and his contemporaries) to expect justice. Nothing so testified to the grim reality of that truth like the 1955 slaying of fourteen-year-old Chicago native, Emmett Till.

Visiting his cousins in Money, Mississippi, on August 24, 1955, the Chicago teen went into a grocery store and allegedly whistled at Carolyn Bryant, a white woman. Four days later, on August 28, Roy Bryant (Carolyn’s husband), and “brother-in-law, J.W. Milam, kidnapped, beat and tortured” the youngster “for hours before shooting him and dumping his body in the Tallahatchie River with a 75-pound cotton gin tied around his neck with barbed wire.”[6] During the subsequent trial, Moses Wright, Emmett Till’s grandfather, risked his life when he stood up in court and pointed out the men who’d invaded his home and kidnapped his grandson. An all-white jury deliberated for a mere hour before acquitting Bryant and Milam who later confessed to the murder during a paid interview with investigative journalist William Bradford Huie. Moses Wright left Mississippi and never returned, losing his home and livelihood along with his grandson.[7]

Only fifteen years old at the time, John Lewis was “shaken to the core.”[8] For him and the people of his generation, the murder of Emmett Till and the subsequent colossal miscarriage of justice stood as grisly metaphors for the racist rot perverting people’s hearts and the nation’s justice, political, and economic systems. The message to John Lewis and his contemporaries was clear: No aspect of black life was safe from racist predators or the system in which they lurked.

There was nothing new about the message, but the messengers had miscalculated. They didn’t foresee Mamie Till’s decision to have an open-casket funeral so the world could see how they’d bludgeoned her son’s face into a grotesque horror. They didn’t count on Emmett Till’s ghost uniting black and white people into a movement of love and non-violence that would expose the cowardly weakness of hate-mongers. And they absolutely didn’t expect to awaken the lion in John Lewis who’d take the fight to them.

The young lion grew into an intrepid warrior who was eventually elected to Congress to help oversee the system which, in another set of hands, had remained idle throughout the 20th Century while black people had been getting lynched, bombed, pillaged, and mobbed. Ever vigilant and ever determined to safeguard the citizenship gains won with blood, injustice became the prey whenever it confronted John Lewis. He’d lived long enough to know that the constrictor, racism, never really slept, never really went away, and never tired of attempting to coil itself around other people’s liberty to choke the life out of their freedom.

And then, just like that . . . he was gone.

“What do we do now?” I wondered, surfing the net for articles on Lewis. “How much harder will it be to fight without this lion to check the enablers of chaos and injustice?”

As if he’d been listening to my thoughts, the words of John Lewis showed on my computer screen from a message he’d “tweeted” in 2018: “Do not get lost in a sea of despair. Be hopeful, be optimistic. Our struggle is not the struggle of a day, a week, a month, or a year, it is the struggle of a lifetime. Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.”[9]

The lion, John Robert Lewis, was gone but his words live to inspire lions in the rest of us. Onward!

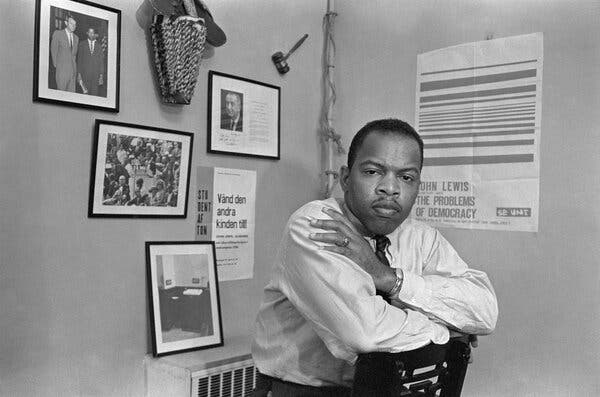

Cover image is John Lewis in 1967. Photo Credit: Sam Falk/The New York Times

[1] From the CNN Interview and article “John Lewis Marches Across the Edmund Pettus Bridge to Commemorate 55th Anniversary of ‘Bloody Sunday’”. See: https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/08/politics/john-lewis-bloody-sunday-anniversary/index.html. Accessed on 20 July 2020.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] See Project Gutenberg found at the following web address: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/408/408-h/408-h.htm#chap02. Accessed on 18 July 2020.

[6] From the online San Antonio Express News on June 12, 2020, author Cary Clack refers to the book Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement, in which Congressman John Lewis recalled that Emmett Till’s murder had left him shaken to the core. See: https://www.expressnews.com/opinion/columnists/cary_clack/article/Clack-This-generation-s-Emmett-Till-moment-15336352.php. Accessed on 19 July 2020.

[7] YouTube Video from the documentary series “Eyes on the Prize,” Part I, “Awakenings: 1954 – 1956, America’s Civil Rights Movement”. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NpY2NVcO17U. Accessed on July 18, 2020. Also, in the episode “Brave Testimony” of PBS’s American Experience has an episode

[8] See citation number six for source data.

[9] From article “’Get in good trouble, necessary trouble,’ Congressman John Lewis in His Own Words”. USA Today [online]. See: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2020/07/18/rep-john-lewis-most-memorable-quotes-get-good-trouble/5464148002/. Accessed on July 21, 2020.

A potent and powerful message highlighting the courage and endurance of John Lewis, and a poignant tribute by you, Fred Johnson, of his impact on your own life. May John Lewis rest in power.

Thank you for this, Dr. Johnson. As much as I could enjoy a reflection like this under the circumstances, I appreciate the prose…and the passion.

Hi Fred,

This is a great message you have written. John Lewis was a great man. His message must be forever taught in every home in America. I will send this out and hopefully some tech person will post to communicate this message.

History as you know is a 20/20 tool. Is it possible to use History results and modify future plans to get better Positive future results? As Mr. Lewis said, “Never be afraid to get into Trouble”.