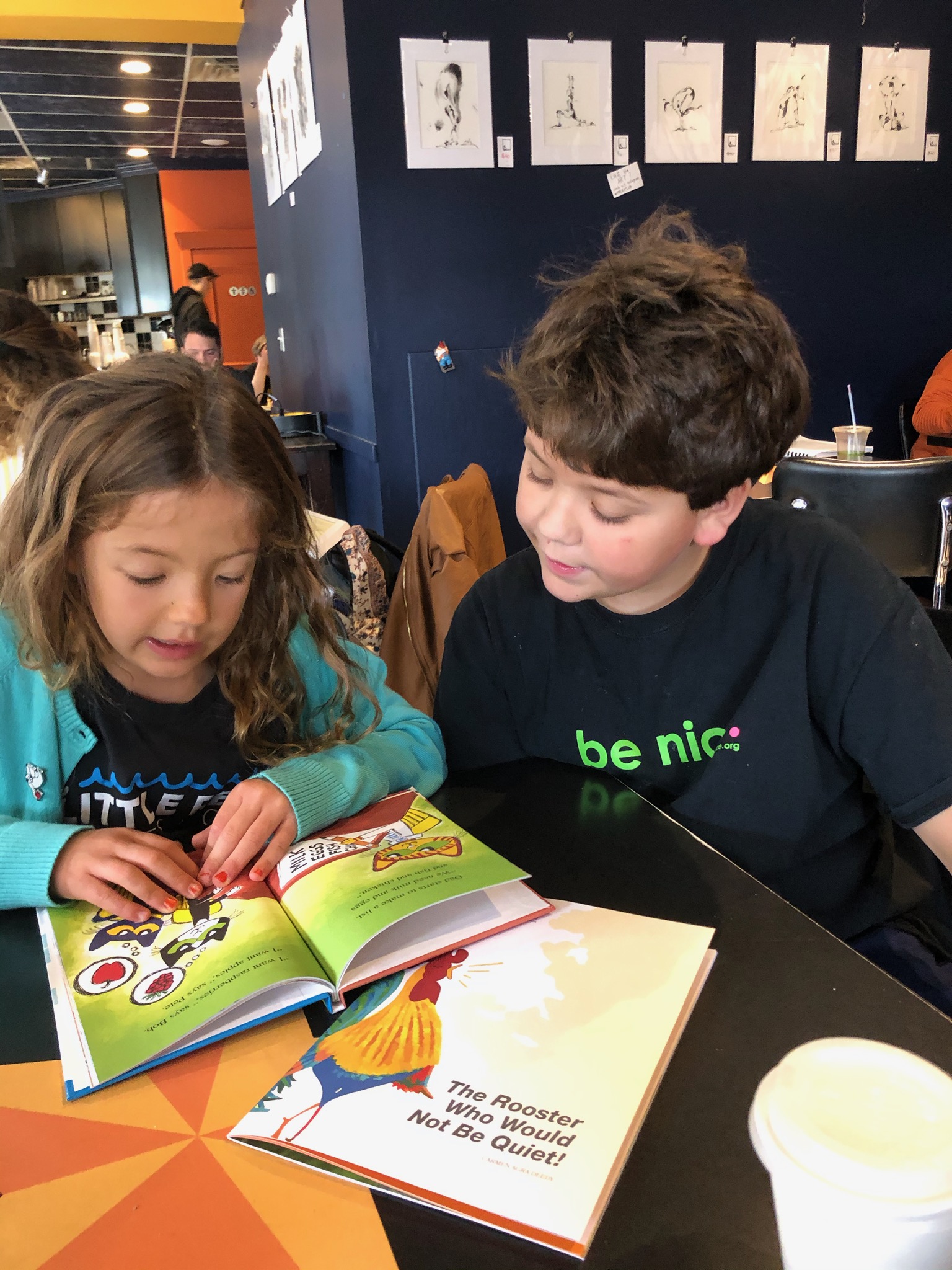

‘Community’ is a word that easily came to mind on Tuesday afternoon in the Martha Miller Center first floor rotunda. The crisp November wind was just sharp enough to make the walls feel like a reprieve, and the sun poked through windows to illuminate eager participants. Seventy people filled the room, with Hope College faculty and students lining the perimeter and Holland-area community members occupying the small round tables scattered in the middle. The circular room and cozy seating arrangement acted as an invitation for participants to interact as well as listen. Conversation bubbled and bounced along the tables until the moment Dr. Doshi of Hope’s Communication department stood, wielding a microphone.

The lecture, sponsored by Hope’s Communication department, featured Dr. David Myers, Amy Otis-DeGrau and Rev. Dr. Denise Kingdom-Grier discussing their personal connections with the Japanese internment during World War II and this year’s Big Read novel When the Emperor was Divine. The purpose of the event was to discuss and reflect on one of the essential questions posed by the novel: who is my neighbor?

Dr. Myers opened with the story of a place close to his heart: Bainbridge Island, Washington, where his parents lived early in their marriage and where some of his family still resides. The island community, he noted, was something of an anomaly during the internment period; the close-knit community consisted of several figures who openly spoke out against the internment order and, contrary to what is depicted in Otsuka’s novel, took measures to ensure that interned citizens were welcomed home with their abandoned lives still intact. Most notably, the island’s newspaper, run by Walt and Millie Woodward, was the only West Coast newspaper to object to the internment order. As his story of an island’s resilience and warm-heartedness came to a close, Dr. Myers left the audience with a final thought: nidoto nai yoni. Let it not happen again.

Amy Otis-DeGrau, the next speaker, told of her own family’s experience during the internment. A third-generation Japanese-American, her grandparents, four aunts and uncles, and one-year-old mother were all incarcerated. She shared the story of her family’s lost money, property, history and dignity. She also discussed the famed 442nd infantry regiment, comprised almost entirely of Japanese-American soldiers and one of the most decorated regiments of World War II. While she mentioned the irony of these men fighting on behalf of a country that rejected them, Otis-DeGrau emphasized the fact that many men of the 442nd regiment acted as voices of justice during their time training in Jim Crow-era Arkansas; several accounts survive of 442nd regiment men being punished for speaking out over injustices suffered by African Americans. From there, Otis-DeGrau shared several biblical passages citing the importance of justice in the Christian faith. Scripture, she reminded the audience, is full of calls for justice; anyone identifying as a Christian is called by Scripture to work toward justice. And one cannot work toward justice silently.

Silence, Otis-DeGrau said, comes in many forms. One of the forms, with which she is very familiar, is the phrase “shikata ga nai,” meaning it cannot be helped. It was the phrase which met many of her early questions about the war and her family’s imprisonment, a phrase which communicates the lack of agency experienced by Japanese-Americans during this period in American history. But silence also takes other forms; it is the lack of conversation surrounding the controversial internment, the cursory glance with which this dehumanization and injustice is given, the unchallenged paranoia and prejudice that ran rampant in the newspapers and radio stations, the lack of dialogue even now about the trauma.

We are all connected, Otis-DeGrau claimed, and the point of connection is in our stories. For that reason, she said, it is extraordinarily important to share these stories of inequity. If they are the bonds which hold us together, it is crucial to give them a voice, to give power to those connections, and to use them in our fight for justice.

The final speaker, Denise Kingdom-Grier, discussed justice and the idea of ‘otherness’ in the Bible. Drawing on her experience researching apartheid in South Africa and several biblical stories as she picked up the thread of what it means to be just, she used the well-known story of the Good Samaritan to illustrate what it means to be not only just, but to be a neighbor. The two, she suggested, are closely tied. Kingdom-Grier posited that to be a neighbor is to enter into another person’s story without expecting to receive any benefit from it. Instead of seeing someone suffering and backing away, as the priest and Levite do in the story of the Good Samaritan, it means reaching out, taking initiative, taking an active role in a narrative that is not our own. But that is not all, she said. Using the story of Jesus and the Samaritan woman at the well, she suggested that to be a neighbor also means to give somebody an opportunity to help us and meet our needs; it means to be vulnerable. Potentially, it means allowing conflict to arise so as to come to an understanding.

These three speakers, with their different professional, ethnic, and faith backgrounds offered a diverse but cohesive view of the role neighbors play in our lives, and what it means to be a neighbor. For Dr. Myers, neighborliness abounded on Bainbridge Island as the community raised its voice in solidarity with their incarcerated neighbors and worked to uphold their ties to the community even in their absence. For Amy Otis-DeGrau, the great enemy of neighborhood is silence; the way to reinforce its bonds is sharing stories and speaking out. For Rev. Dr. Kingdom-Grier, to be a neighbor is to allow vulnerability, to enter into another’s story and engage. For all three, though, one thing was noticeably absent; in none of their discussions of neighborhood did they mention physical proximity, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or any other identifiers which are typically used to connect people to a particular community. There were no caveats to the term ‘neighbor’ such as “Christian neighbor,” “Muslim neighbor,” “LGBTQ+ neighbor.” None of their stories included people who were inherently neighbors by virtue of their social status, ethnicity, or physical location. To all of them, neighborliness is an action; to be a neighbor is to be a person of action.

With that in mind, the question “who is my neighbor?” seems to be almost inappropriate; the lecture and novel together seem to suggest that instead of attempting to identify and evaluate others, maybe we ought to look inwards and identify ourselves. If we are looking outside ourselves for neighbors perhaps we’ve missed the point of the novel, the lecture, and scripture. In the very act of asking whether or not someone is a neighbor to us, we shy away from neighborhood; we hesitate to enter into another’s story, we stay silent in our equivocation, we mark them as separate from our established community. In that moment of reluctance they may be a neighbor, but we are not.

The question becomes then, not how do we find neighbors, but how do we be neighbors. Being a neighbor, much like being a Christian, a student, or a member of the Big Read committee is not so simple as choosing a label, sticking it onto ourselves and moving on. It is an action; rather, it is many repeated actions. It is speaking out, it is standing up, it is entering into story after story that is not our own. It is going through the world asking not “who is my neighbor?” but “whose neighbor will I be?”

Contributed by Annika Gidley

Annika is a junior at Hope College double majoring in Creative Writing and Spanish. When not reading, writing, or talking about Harry Potter, she can be found at the local coffee shop or the nearest Big Read event.