Campus Community,

As we enter the last few weeks of this Spring 2021 semester, we acknowledge that the past year has been mixed with much pain, division, and hurt. As many of us were planning on the details of summer research and Fall 2020 details, we were also grieving the brutal murder and killings of many. Of these, the murder of George Floyd gripped and shook the world–causing many to pause, lament, and wrestle with systems and practices that have subjugated too many based on the physical form God put his divine breathe in.

While we may not know the precise end of the current Chauvin trial, we do want to remind our campus community of our Mission, Christian Aspirations, and Virtues of Discourse. We are living in very challenging times–grieving a pre-pandemic life and dealing with the ramifications of racist sins.

We know there are many different challenges that distinct individuals and groups have weathered during this season–often in disparate manners. This note both acknowledges the building emotional load we are all trying to carry and shares some resources we continue to provide students, faculty, and staff in light of these challenges.

CDI Resources

CDI will host several virtual townhall meetings targeting students, faculty and staff respectively. CDI staff will be available to assist individual students, as identified, with other supporting departments as appropriate.

CAPS Resources

CAPS has same-day scheduling for appointments – just call the CAPS office at (616-395-7945) to arrange an appointment. There is also an after-hours crisis on-call service available for times when the CAPS office is closed. This service can be reached by calling the CAPS number and following the recorded prompts.

Faculty & Staff Resources

Our Employee Assistance Program has a 24/7/365 hotline available. Just call 1-800-448-8326 to immediately connect with someone for support. Here is a newsletter (1Hope login required) focused on identifying resources and methods to help heal in the midst of national and global tragedies.

Spiritual Resources

I. Personal Support: Hope’s Chaplains are available for prayer, conversation, and support for any and all students struggling in this season. Feel free to reach out to Trygve Johnson (johnsont@hope.edu), Jennifer Ryden (rydenj@hope.edu), Jill Nelson (nelsonj@hope.edu), Paul Boersma (boersma@hope.edu), Bruce Benedict (benedict@hope.edu), Nancy Smith (smithn@hope.edu), and Matt Margaron (margaron@hope.edu).

II. Pray the Psalms. Scriptures to pray in times of Lament: The psalms is the prayer book of the Bible, and within the 150 prayers, there are 42 psalms of lament, and thirty of which are individuals psalms of lament, and the rest are communal. In times of deep grief, uncertainty, anger, frustration, these psalms have been a guide for the people of God. It is also a reminder that God can handle our anger and cries of lament for justice. If you are looking for help to know how to pray I encourage you to use these Psalms as a guide for to pray – both individually and with your friends or community corporately.

These Psalms are often helpful for communal prayers of lament: Psalm 12, Psalm 44, Psalm 58, Psalm 60, Psalm 74, Psalm 79, Psalm 80, Psalm 83, Psalm 85, Psalm 86, Psalm 90, Psalm 94, Psalm 123, Psalm 126, Psalm 129.

For individual Laments these are recommended Psalms to guide you in prayer: Psalm 3, Psalm 4, Psalm 5, Psalm7, Psalm 9-10, Psalm 13, Psalm 14, Psalm 17, Psalm 22, Psalm 25, Psalm 26, Psalm 27, Psalm 28, Psalm, 31, Psalm 36, Psalm 39.

III. Create. In times of pain, anger, and personal and communal trial it is often helpful to write your own prayer of lament to God. Following the form of the psalmists, here is a guide for you to use for your own prayer of laments.

- Invocation – The initial cry to God to take notice

- Complaint – the description of the psalmist suffering against God or some enemy/ies.

- Request – the psalmist petitions God to act on the Psalmists behalf.

- Expression of Confidence – often a recital of God’s trustworthy characteristics or acts in history.

- Vow of Praise – assurance of praise that will follow deliverance.

IV. The Harvey Prayer Chapel is available for you to go and pray individually, or with a Chaplain, or with friends. In the Harvey Prayer Chapel there are resources available, such as journals, Bibles, the Book of Common Prayer and guides for prayers of lament, as well as a prayer wall where you can place your handwritten prayers.

V. Chapel and Worship. Chapels on Monday, Wednesday, and Fridays are open for all students. One of the ways we respond as a community in times of trial is we go to God to worship. To focus on God, his character that inspires faith, hope, and love, and our communal virtues of Hope is a resource for you.

Together, we come as servants of the Lord. We come with a spirit to listen and allow space for the multitudes of ways of grieving and lamenting. We are dedicated to not retraumatize. While we are in unknown seas, our hope is in our anchor–the Lord God Almighty.

On behalf of the following offices:

Office of the President

Provost’s Office

Center for Diversity and Inclusion

Campus Ministry

Counseling And Psychological Services

Public Affairs & Marketing

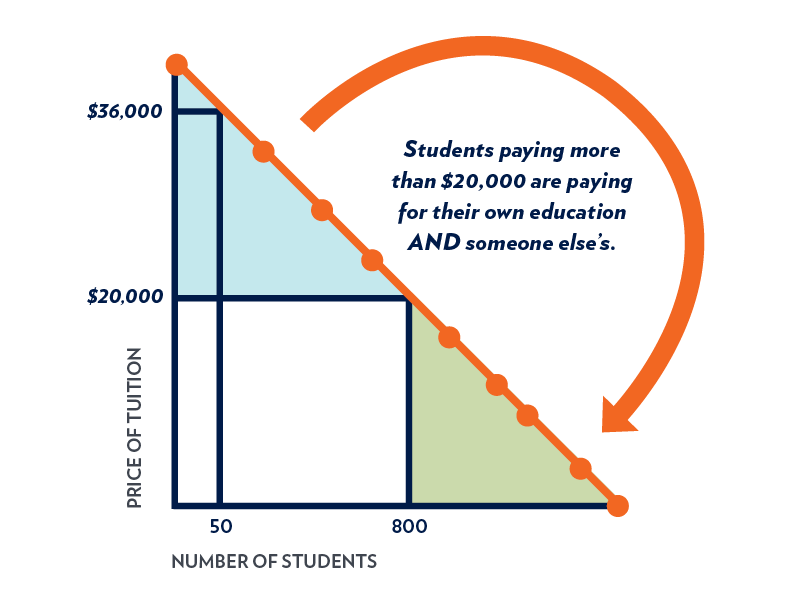

When it came time to select a college, I knew I was going somewhere, but the question I couldn’t answer at that time was how a middle-income family such as my own could afford it. Four years later, I understood—my dad had taken a second mortgage on our home, but even that wasn’t enough. I took on a significant amount of student loan debt in order to graduate from the college I now lead.

When it came time to select a college, I knew I was going somewhere, but the question I couldn’t answer at that time was how a middle-income family such as my own could afford it. Four years later, I understood—my dad had taken a second mortgage on our home, but even that wasn’t enough. I took on a significant amount of student loan debt in order to graduate from the college I now lead.  Enrollments at 4-year institutions have declined 1-2% annually since 2000 (and even higher since the start of the pandemic). The principal reason? Cost—and the inevitable erosion of ROI as the sticker price climbs higher and higher.

Enrollments at 4-year institutions have declined 1-2% annually since 2000 (and even higher since the start of the pandemic). The principal reason? Cost—and the inevitable erosion of ROI as the sticker price climbs higher and higher.