I wondered why I had never heard of him before.

It was 1967. I had graduated from Hope College but was still getting The Anchor, so I was surprised when the issue for February 24 featured a eulogy for the recently deceased Rev. A. J. Muste by Dr. D. Ivan Dykstra, Hope’s august professor of philosophy. The Dutch-born Muste, I learned, was a Hope alumnus, Class of 1905, who it seemed had been a world-renowned pacifist; only a month before his death he traveled to Vietnam to protest a war he insisted he “could not reconcile with the Sermon on the Mount.” A memorial address by Hope’s President Calvin Vander Werf praised Muste as one whose calling “was to serve the Prince of Peace.”

So why had I never heard of him?

As it turned out, the reason was obvious. Frustrated by what he saw as his church’s complacent indifference to the poor, he had briefly allied himself with Marxist-Leninism, going so far as to meet with the Russian radical Leon Trotsky. It did not take Muste long to see through to the fallacies of Communism and the potential violence in Trotsky’s character, and in 1936, in the Church of St. Sulpice in Paris, he experienced an almost mystical return to Christianity. “Without the slightest premonition of what was going to happen, I was saying to myself, ‘This is where you belong’: and ‘belong’ again, in spirit, to the Church of Christ I did from that moment on.” But his alma mater and the church of his baptism had a long memory, and despite his radiant witness to the love of Jesus he was looked at with suspicion.

Muste might have remained in the shadows of Hope’s history had it not been for the efforts of another saint, the late Professor Donald Cronkite, who in 1985, the hundredth anniversary of Muste’s birth, endowed an annual lecture in his honor. “I’m grateful for Muste,” Don acknowledged, “for the times I have stood on my principles because people like him have shown it could be done.” So, I was honored when, many years later, I was asked to chair the Muste Memorial Lecture committee.

Serendipity. One summer day — the actual year escapes me — someone in Hope’s Advancement office asked me to meet Mary Neznek, a Hope alumna with her own admirable record of devotion to the cause of peace and justice. Mary suggested that we invite as a future lecturer a man named David McReynolds, a veteran of the War Resisters League who had worked closely with Muste for many years. When I expressed concern about Mr. McReynolds’s age, she proposed that we might send someone to videotape his memories.

I immediately telephoned my former colleague Dr. David Schock. David had an impressive record as a maker of documentaries, including six on unsolved homicides in Michigan. As I expected, David took the bait: when we met at a local coffee shop to discuss the project he had already collected and studied the available books on Muste and gotten in touch with McReynolds. Mr. McReynolds agreed to meet us in New York, but he recommended that we first visit a man named Brad Lyttle, another long-time associate of Muste, who was then living in Chicago.

This was the start of what turned out to be a whirlwind odyssey of unforgettable encounters, as one after another of Muste’s living friends and co-workers joined our list of subjects. Mr. Lyttle in his cluttered home near the University of Chicago came first, an elderly man whose face grew radiant with enthusiasm as he recalled his work with Muste’s memorable projects: the Polaris Action anti-nuclear protest, the confrontation at the Mead Airforce Base, where seventy-five-year-old Muste climbed over the fence into the grounds, the San Francisco to Moscow Walk for Peace, the Quebec-Guantanamo Peace Walk, the Sahara Project.

David and I then boarded a plane and interviewed Mr. McReynolds—another cluttered apartment, this one presided over by his imperious cat, Shaman—and from thence flew to California to meet Muste’s last secretary, a delightful little lady with tattooed eyelids and an infectious laugh.

Back in Michigan, our meeting, over coffee, with the Rev. Art Van Eck and Muste’s niece Dorothy Vander Klipp. And of course the unforgettable afternoon with Muste’s grandson Peter Muste, who spoke with manifest emotion about his grandfather. The fruit of these adventures was David’s exceptional production of four full-length documentaries, Radical for Peace, available free of charge (what would A.J. Muste want, we asked ourselves). Without for these, much of Muste’s legacy would have been lost.

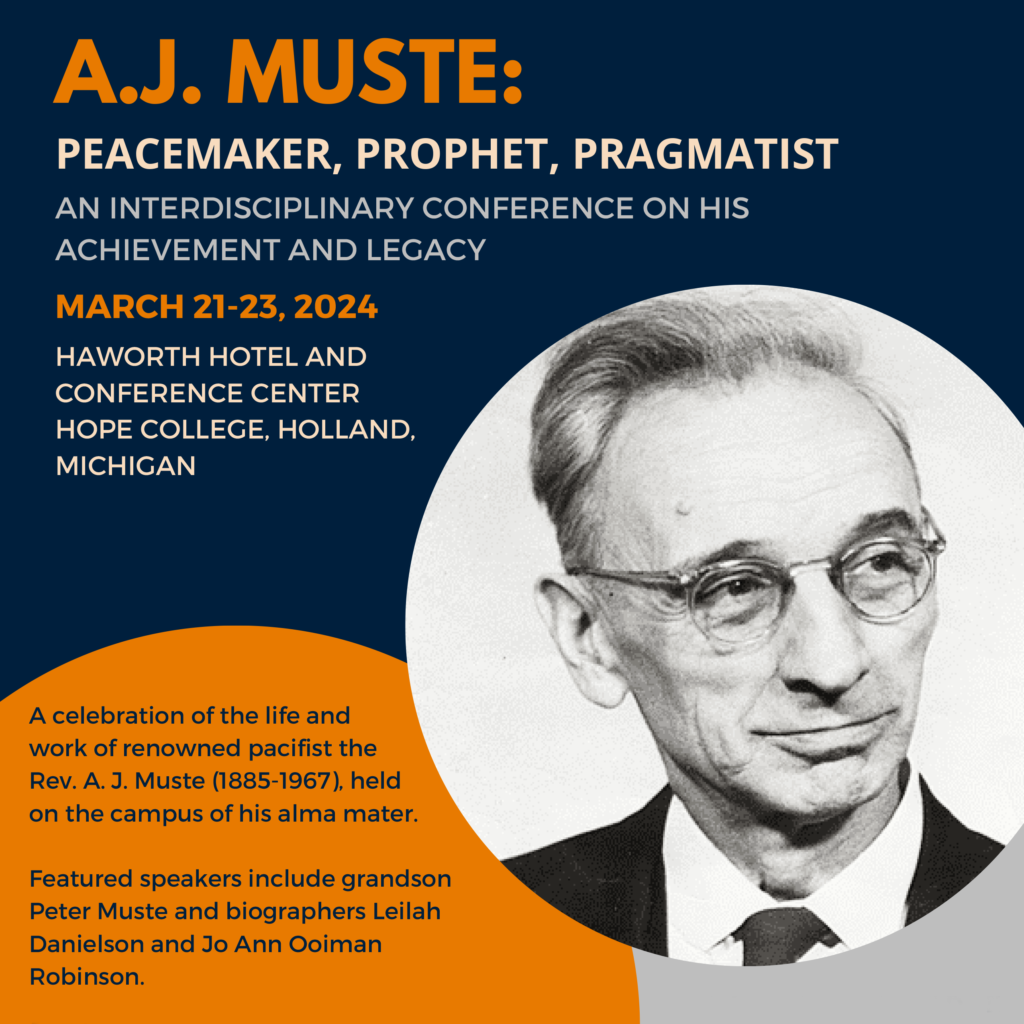

So, what was next? If I remember right, it was David who first came up with the idea of a conference here at Hope, and I will be eternally grateful that he talked me into it. With the help of my two colleagues Curtis Gruenler and Steve Bouma-Prediger, “A. J. Muste: Peacemaker, Prophet, Pragmatist” took place at the Haworth Hotel on Hope’s campus from March 21-23; it featured addresses by Peter Muste, Muste’s biographers JoAnn Robinson and Leilah Danielson, and the Executive Director and Chairperson of the A. J. Muste Foundation for Peace and Justice in New York. The dubious portrayal of Muste (“pale and patrician”) in the recent film Rustin was confronted by Danielson and Martha Reineke of the University of Northern Iowa.

We were also privileged to mount a session on African pacifists by Hope May of Central Michigan University and Keith Snedegar of Utah Valley University. And what might A. J. concern himself with now? Filmmaker Joshua Vis, the Rev. Chris De Blaay, Mary Neznek, and the Rev. John Kleinheksel were on hand to analyze the current crisis in Israel-Palestine. We heard an illuminating presentation by former Hope faculty member Timothy Pennings on Muste’s contemporary and fellow pacifist Bertrand Russell; Curtis Gruenler contemplated Muste’s ideal of friendship. And the wonders of Zoom let us hear from Ariel Gold of the Fellowship of Reconciliation and Dick Flacks, a founding member of the legendary Students for a Democratic Society.

But by far the most moving contribution came from Brad Lyttle. Now ninety-seven and nearly blind, Brad was transported to Holland by a loving caregiver, Ted Alexander, and spoke from memory of the years he had spent working closely with Muste as his right-hand collaborator and, indeed, disciple.

All in all, the conference will stand in my memory as one of the blessed events in my career at Hope College. Never have I participated in an academic meeting so manifestly inspired by, if I may say so, mutual love. I am thankful to David Schock for jumpstarting the whole thing; to Steve and Curtis for helping to float it; to Roger Baumann for his encouragement.

And yet Muste’s name remains unknown to many Hope faculty and students. And, indeed, to the general public.

Abraham Johannes Muste was probably the nearest to a holy man that Hope College has ever produced. I am grateful that our conference did its part to contribute to his legend.

Goed gedaan, goede en trouwe dienaar.

Well done, good and faithful servant. Enter into the joy of thy Lord.

—

Dr. Kathleen Verduin is Professor of English at Hope College and Chair of the A.J. Muste Memorial Lecture Series Committee.

Read more about A.J. Muse in Verduin’s essay “Who was A.J. Muste?”, published in the Spring 2024 issue of News from Hope College.