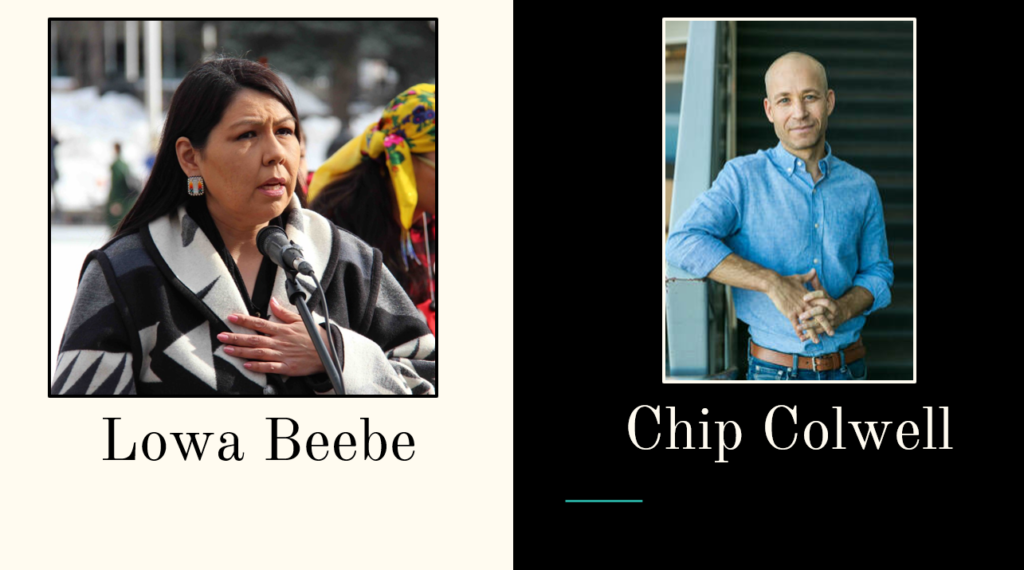

I learned some years back about land acknowledgements from Lowa Beebe and Chip Colwell.

I never thought much about whose land I lived on until I worked with a group of Native Americans on a series of pow wows from 2005 – 2009. One of them had a dream—a literal dream—of offering a pow wow to Hope College as a gift of reconciliation. The settlers who founded the city and the college drove nearly all Natives from this place shortly after they arrived, and yet he was offering this gift to us. His gesture moved me deeply. It still does.

I like to begin public addresses and meetings, therefore, with a land acknowledgement. This, for example, is at the top of my course syllabi:

Anthropologist Chip Colwell suggests that we begin meetings, services, and gatherings of any sort by recognizing the original owners of the land we currently occupy–a “land acknowledgment.”

Let us begin the semester, then, by respectfully acknowledging that we meet in this class on the traditional land of the Odawa, the Pottawatomi, and other Anishinabek people who were forced to relocate when a contingent of Dutch settlers moved into this area in 1847. We recognize the continuing presence of the Anishinabek on this land, and their unique and enduring relationship with their traditional territories. We recognize, too, that those of us from Western cultures have not treated the land well. We have an obligation to clean up the pollution and reduce the suburban sprawl that have poisoned and damaged the land, air, and water in so many ways.

“The land you walk upon, whether it be city streets, country lanes, or suburban cul-de-sacs, is Indian land. There are echoes beneath your feet that are there to be heard if you are willing to still your mind and listen to your heart.” — Kent Nerburn, Neither Wolf nor Dog

Many people are concerned that land acknowledgements are merely performative, including Cherokee scholar Joseph Pierce. Cherokee pastor and professor Stephanie Perdew shares those concerns and suggests ways to make an acknowledgement less of a momentary exercise and more of an on-going commitment to justice for American Indians. You can find additional ideas for that here.

It’s a quick and simple recitation. But it helps me look at my home and my workplace in a different way. It helps me look at myself in a different way. I understand that I am part of the story of the colonization of this land. I didn’t ask for it, but I benefit nonetheless.

Thinking more clearly, more historically, more honestly about the land on which I live, work, and worship helps me think about other things, too. The Dutch who moved into this area in the mid-19th century were part of the second wave of Dutch immigration to North America. The first, of course, were the settlers of New Amsterdam. It became New York in 1664, but many people of Dutch heritage remained, and even today they are a significant presence in New York and New Jersey.

The Dutch were active in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and at the turn of the 18th century, 42% of all households in New York City owned slaves. Only Charleston, South Carolina, had more (Oltman, 2005). Sojourner Truth was born enslaved in Ulster County, NY in 1797. Her first language was Dutch. Enslaved people created significant wealth for those who owned them without ever earning one red cent for themselves, their families, or their descendants. When my employer, Hope College, was chartered in 1866, the contributions of prosperous Dutch Americans from back east were critical to its survival (Nyenhuis, 2019; Bruins and Schakel, 2011). They had money to send Hope because of the wealth they amassed, in part, through slavery.

Think about that. The education of those who have studied here at Hope was made possible, in part, by the unpaid work of people who had no chance at an education for themselves. The careers of those employed by Hope College—me, for example—were made possible, in part, by the unpaid work of people who had no chance at a career for themselves. I want to remember them as I do my work in this place. I want to see them in the shops and the barns and the fields and the kitchens. I want to imagine their children and grandchildren, and what they would have accomplished if the wealth their forebears created had gone to them instead of to me.

That’s why I say that the history we inherited has become the history we inhabit. Hope College would not have survived without the early contributions from prosperous Dutch Americans back east. There would be no Hope College today. 3,000 students would be studying somewhere else. 900 employees would be working somewhere else.

This is not revisionism, or propaganda, or left-wing ideology, or an unpatriotic interpretation of history. It’s telling the truth and facing the facts. And it matters. When we acknowledge the land, when we acknowledge the facts, we are freed from the need to justify a racist past and motivated to find ways to move toward an antiracist future.