Written by Anna Stowe, Hope College Creative Writing Major and Student Managing Editor for the English Department

It’s 7 pm on November 13. Dusk has etched its colors across the sky, grayish-purply blues gathering in the shadows. The first stars glisten in the sky, soon to be obscured by dense cloud cover and drumming rain. Inside, though, it’s warm, Michigan heaters raging against the dream of snow.

Tonight, the Jack Ridl Visiting Writer’s Series welcomes yet another mentor/mentee duo intimately connected to Hope’s literary past. Successful authors and adventurers, Chris Dombrowski and Jack Ridl, the namesake of VWS, meet to share their work and their wisdom. The Schaap Auditorium fills and the lights dim. Throughout the reading and in the following Q&A, Dombrowski and Ridl reflect on the writing life, the natural world, and our place in it. Their language takes us to soaring heights, to moments of sunshine, the nature of humanity, violence, and beauty. Read aloud, the images come to life, forming a community around themselves.

Chris Dombrowski takes the stage first. His face is weathered, smile lines carving deep into his skin. I wonder if they are the marks of his love for the place, of the Montana rivers that he calls home. Immediately, he draws the crowd in, joking about his nerves. Readings may be routine, but there’s something different about reading with Jack Ridl, one of his early mentors. Dombrowski explains, “His teaching is something that you only come across once every few lifetimes. Jack Ridl made it all possible. He encouraged me in what I didn’t know then was my calling.” From Dombrowski’s perspective, our lives are the profound expression of the people we meet, a tapestry of moments and influences that may or may not seem important at the time of creation.

Following this reflection, Dombrowski read a prose poem called “Name-Dropping,” two passages from his memoir, The River You Touch, and a final poem titled “That.” As he reads, his voice is lilting. Regarding The River You Touch, Dombrowski explains that a sliver of Jack Ridl was captured in a fictionalized character, Ralph, even though that character was dominated by another individual from Dombrowski’s life. Despite writing a memoir, this conflation did not bother Dombrowski; rather, the essence of the storytelling remained key. In the voice of Jack Ridl, Ralph captures Dombrowski’s love of Montana with the words, “Maybe the best thing that happens from this whole deal is that you learn where you’re supposed to be” (275).

As for the prose poem “That,” Dombrowski again discusses the influence of Jack Ridl’s writing. Recalling reading one of Ridl’s dog poems, Dombrowski states, “I remember thinking I would love to put a dog in a poem the way he does… And I like to think this poem does that.” Spoken with a smooth rhythm, the dog Dombrowski creates is safe and loved, having borne hardship and survived. At the heart of Dombrowski’s writing is the reflection that “When you’re in love with a place or you’re in love with a person that’s the only thing that really matters.” Vivid, intimately connected to the land and to the people that inhabit it, Dombrowski’s writing contains a longing for the long-lost days of a simpler time and the wild wonder of place.

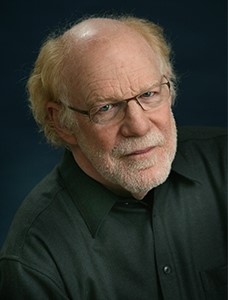

Following Dombrowski’s reading, Jack Ridl takes the stage. He takes the stairs slowly and lays his cane down behind the podium. His tumultuous white hair peers out from behind the podium. Lifting the mic, Ridl’s soft voice fills the room, gentle and contemplative. “What? You wouldn’t want to be a dog?” (52). My breath catches in my throat.

The poem he reads is one of my favorites from All At Once. I’d told Jack Ridl earlier that I loved how much he wrote about his dog and about gardening. I’d told him his writing felt like home, that it reminded me of my mother. Applause rippled through the room at the poem’s closing. Jack shook his head, “I have one little request. After a poem, if you feel like applauding, instead take a breath.” And each time he reads a poem, I can hear that sigh, a soft breeze filling the auditorium.

Reflecting on the relationship he shares with Dombrowski, Ridl says, “I want to thank Chris, but I don’t know how. It’s remarkable to read with a student who has gone on to hang out with authors and I hang out with my dog.” A soft chuckle spreads throughout the auditorium. Ridl is remarkably casual despite being woven with insight.

Ridl reads poem after poem, capturing his listeners. His writing spans from the profound to the ordinary, all in that same quiet voice. In between poems, Ridl considers moments of his life that inspired his writing. In one such interlude, he reflects on the safety he found on the west coast of Ireland: “The only place that I have ever said I was a poet was in Ireland. The poets, the musicians, the artists, are considered tradesmen. The arts are fundamentally necessary. And I said it on the third day I was there. It was the first time in my entire life I’d said I was a poet.” This idea is reflected in the poem “Before What Came Before,” which considers the beauty of Ireland (despite its hardships) and its wide, welcoming spaces that somehow scream home (79). Poetry imbues the Irish landscape, forging intimate connections through place and language.

Other times, Ridl broadens his scope to reflect upon larger American culture. “In this political era, I wish it was life, liberty, and the pursuit of empathy. But it isn’t and we’re all still out here trying to be happy.” Aloud, Jack Ridl’s poems come to life, their sound seeming to dance through the air. His words draw the crowd in, eliciting a response. Sometimes laughter, sometimes murmuring, but always engagement. Perhaps it’s because of the simple honesty of his writing—poems capturing single, intimate moments that carry the weight of the communal.

Following the reading itself, Ridl and Dombrowski settle into chairs, poised to consider the questions of the audience. Ridl fiddles with his cane, draped over his knee. The majority of the Q&A centers around the writing process and the vulnerability of writing.

Dombrowski begins the conversation by explaining that trustworthiness stems from vulnerability,

—“vulnerability is the writer’s greatest defense. You must establish trustworthiness to get to vulnerability and you must also have precision of language.”

Utilizing language effectively is crucial because writing is an act of communication—not just an act of expression. With this in mind, Dombrowski articulates the importance of revision which must be done ruthlessly: “I love the revision process because as it’s happening the story is getting more graceful, more efficient, more communicative.”

Dombrowski encourages listeners to “trust the language to get at what you’re trying to say. Sometimes it’s the language rather than the musicality of the path that draws people to truth.” Reflecting on his writing, Dombrowski considers the natural lyricism of his prose: “I’ve become comfortable with my prose style having adopted a kind of lyricism. In that sense, I have less of a sense of guilt for abandoning poetry.” Regardless of the writing style, Dombrowski emphasizes the importance of maintaining a sense of self, observing the world, and writing about that world in the most communicative way possible. Language comes first, even when writing about the deeply personal.

Likewise, Jack Ridl considers the importance of poetry and its writing process. Pondering his craft, he says, “The poet is trying to use words to create that for which there are no words…You must be able to articulate sense. But there’s another kind of knowing and that’s where the poem is—in the inarticulable. At the end of the poem, the poetry restarts.” A poem should structurally be a complete unit and yet it should also draw the reader to itself once more by some twist of the language or of the feeling it elicits. The poem must create poetry.

Further, Ridl sees everything as a source of inspiration, considering poetry as an art that made his life worth living. Looking back on his life, Ridl highlights the importance of putting pen to paper:

“What I discovered is that poetry is one of the best friends I’ve ever had. I’ve never been bored and I don’t take any credit for it. It’s all due to poetry. I can turn anything—it’s just how you turn it. Don’t ever tell me you can’t think of anything to write. You find out during the writing—not after.”

Through storytelling and example, Ridl portrays poetry as something fundamentally necessary to humanity. In his view, writing serves as an invitation to intimacy with creation and with one’s fellow man: “Writing should help you feel less alone, that somebody out there gets it.” Fiddling with his cane, Jack speaks a final blessing over the audience: “All writing holds value simply in the act of creating, of learning. Writing brings that which you would not have without it… I just want it to be important for you.”