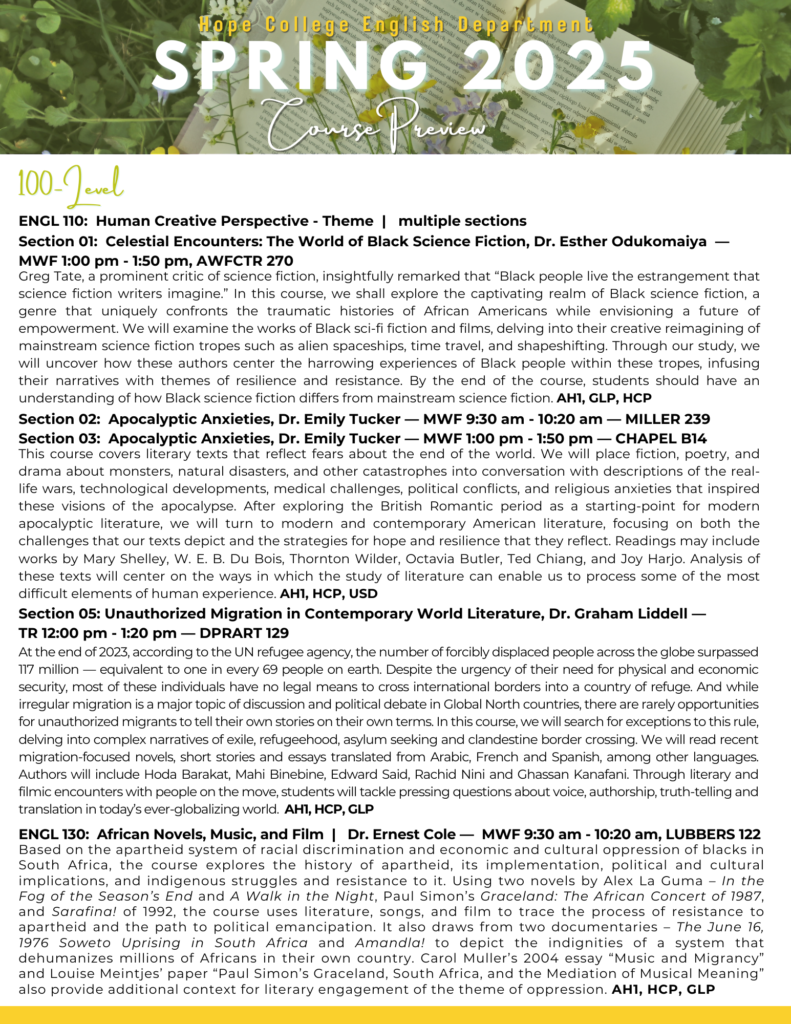

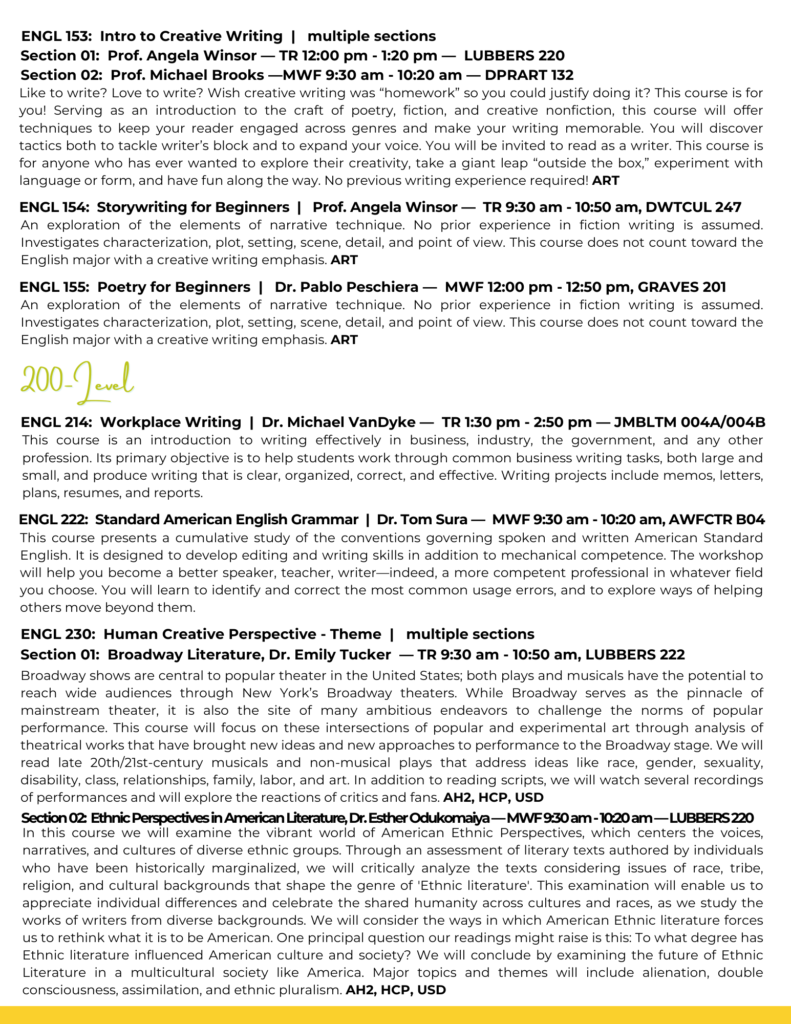

Written by Anna Stowe, Hope College Creative Writing Major and Student Managing Editor for the English Department

2024 Critical Issues Symposium

The Jack H. Miller auditorium fills slowly. There’s nothing special about today’s set-up, only a lectern poised in the center of the stage. It’s unassuming, even ordinary, a design choice that soon becomes clear. As the clock strikes 10, Provost Griffin takes the stage, introducing the 2024 Critical Issues Symposium. For more than forty years, CIS has been an opportunity to consider intellectual topics, a space for engaging ideas, and an opportunity to emphasize curiosity among the Hope College community. This year’s topic considers processes for engaging with a world of differences.

The keynote speaker is Chloe Valdary, who created the Theory of Enchantment. This framework for approaching the world aligns with Hope College’s model of the virtues of public discourse: the courage to challenge, honesty to speak truth in love, the humility to listen, the hospitality to welcome, and the patience to understand. As we would discover, Valdary’s approach to engaging with difference through enchantment also resonates with the practice of reading, writing, and discussing literature.

The auditorium crackles with applause as Valdary takes the stage. Arranging her papers, Valdary’s powerful, calming voice fills the room. “Pardon my exuberance, but I find myself overwhelmed with joy…” With these words, Valdary begins singing a portion of ‘How Great Thou Art.’ This song became the refrain of her speech.

“Then sings my soul, then sings my soul. I must sing—I need to sing—all day long and all throughout the night of the wonders made by the divine hand. And it is this desire that led me to the Theory of Enchantment. I marvel at the universe and I stand in awe of the miniature universes every single one of you are. Then sings my soul, then sings my soul.” Structurally, Valdary’s speech follows the elements, the forms through which we experience the world and each other: earth, water, wind, fire.

First, the earth. Recalling a recently finished book called Spell of the Sensuous by David Abram, Valdary explains that the natural world possesses an intelligence that is not ours but is, by relationship, related to ours. Functionally, the land and the animals demand our respect for they too are created things that are not diminished by human failings. It is the principle of Komorebi, a Japanese word translating to sunlight leaking through trees. As the wonder and beauty of light moves through the leaves, so it moves through us. “This is enchantment: part of the complexity of what it means to be human. Then sings my soul, then sings my soul.”

Second, water. Water is baked into language, is necessary for human survival on its most basic level. The body is made up of water—the brain is about 75% water, kidneys around 79%. This too is part of the complexity of what it means to be human. “And so I sing of water, that which flows within and without. Then sings my soul.”

Third, wind. According to Native American tradition, the wind flows in many directions—up, down, sideways, through us, and in us. “I could not sing or speak without the wind for speech is but sounded breath. Wind is the breath of the land itself. It is the spirit of freedom and it pushes and pulls, pushes and pulls us all forward.” And yet, so many of us take this beauty, this connection to the world, for granted. We see breath as something of survival, not something intrinsically connective. Valdary reflects on how she, like many of us, treats the wind in her everyday life: “In my waking hours, I do not breathe deeply enough, I do not take time to notice, and I do not take time to breathe from the diaphragm the way I did when I was born. But in some moments when I am still I remember the sacred wind and the breath that are one. From the wind and the breath, we can learn freedom, to be fully engaged by whatever rises. This too is part of the complexity, the beauty of what it means to be human. Then sings my soul.”

Fourth, fire. It is fire that gives us sensation and metaphor: light and dark, hot and cold, internal and external fire. In this image, fire is what brings about willpower, anger, and rage as energy combusts within us. Fire signals that our needs have not been met or that our value systems have been dishonored. Fire prompts us to defend ourselves. Recalling Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Letter From the Birmingham Jail, Valdary explains: “We must channel our anger productively and constructively so that it moves in a way that is healing without burning down the forest. Fire has a dual nature: rage/fellowship, bitterness/communion, hatred/love. This too is part of the complexity. From fire, we learn to wield power, constructively or destructively. So sings my soul.”

But what do these elements have to do with each other and with the broader human experience? Valdary is clear: “The divine hand which conjured the elements into being also brought me into being. And therefore, I am the very frequency of love. No matter what, I then have faith in my life for I am the frequency of love itself.”

The natural elements form the basis of Valdary’s Theory of Enchantment: “It is easy to forget that life itself is a prayer. It’s easy to forget when [the chaos of life steps in]. And I forget that the fire, the water, the wind moves through ‘them’ as well as me. I created the Theory of Enchantment to help myself and others remember.” This Theory is divided into three basic tenets:

- Treat each other like human beings, not political abstractions.

- Criticize to uplift and empower, never to tear down or destroy.

- Root everything you do in love and compassion.

Drawing on both Maya Angelou and James Baldwin, Valdary explains that humans should never be treated as objects. Regardless of differing views, we have all been created; we all share the frequency of love given by the Creator. Hatred and insecurity cause us to lash out against things that challenge us. Met by love, change is possible.

Valdary is clear in her exhortation: “As a being you are durable and strong like the earth, constantly changing and transforming like the water–not an object, not a fixed thing. Feelings and emotions that come and go like the wind. Do not deny or repress your feelings for they will return with a vengeance and you will compulsively act them out like the fire.” The only way this changes is if we remember that we are the frequency of love ourselves. In light of this, all our actions become an act of prayer, an overflowing of the love that has created us.

“Become love. Embody that which you already are. Reject things that seek to turn you into an object, a fixed thing. For you are a universe in miniature, constantly becoming the very chant in enchantment. Then sings my soul, then sings my soul.”

It is enchantment that connects everything. It’s not enlightenment, not an overpowering light–enchantment is about holding light and shadow in balance rather than light overwhelming everything. All these things make up the complexity of who we are. And there is no light without darkness–it’s built into the fabric of our existence. “If we can hold that delicate balance, then we can spread that compassion to others.”

Following this encouragement, Valdary read the poem “Please Call Me By My True Names” By Thich Nhat Hanh. The poem serves as an example of what Valdary has highlighted thus far. There is always room for compassion, for acknowledging the humanity in everyone—even those who are ‘against’ us or who do horrible things. There is space to acknowledge the rhythms of the natural world, to see complexity as beauty. There is room to see everything in life as a form of ongoing prayer.

But what does this talk have to do with English? As scholars and makers of literature, how often do we really come into contact with these conflicting relationships?

The answer? Every single day. Just as it is important to engage with many voices whether we agree with them or not, so too is it important to engage with literature from different times and cultures. In the pages of books, we learn what it means to be brave, to be wise, to be flawed, to be human. We enter and exit the imagination and experience what it is to be enchanted with the world and the beauty that fills it. Through literature and writing, we encounter voices and lives that are vastly different from our own—that contain ideologies we may fundamentally disagree with and that may offend us. Tasting complexity through literature and applying what we have learned to the outside world, we step into the Theory of Enchantment.

Authors of the past were once of the present; their writing is shaped by the world in which they lived, by their beliefs and experiences. In analyzing their works, there is room to criticize and praise, moments of insight that became critical for ongoing thought processes. As for love and compassion, these can be applied indirectly—even in connection with modern society. The ideologies of the past influence the thoughts of today. We can engage more effectively with the current climate by understanding these ideologies. Such language and connection is that of poetry. And it is this quality that Valdary’s speech takes on. Through repetition and imagery, Valdary’s words are memorable and applicable. They are enchanting.

Beyond these qualities, Valdary’s speech itself reveals the value of engaging with literature while pursuing the Theory of Enchantment. She draws on Martin Luther King, Jr. Maya Angelou, and James Baldwin—all historically located thinkers, writers, and speakers. Their ideas are not merely centered in their own time—they are foundational to the present.

Literature and writing. The past and the present. Earth, water, wind, fire.

Then sings my soul, then sings my soul.