Discovering Chasing Beauty

Written by Anna Stowe, Hope College Creative Writing Major and Student Managing Editor for the English Department

Deep in the basement of the Van Wylen Library, you’ll find the Rare Books Room. Lining its walls are hundreds of books ranging from first-edition novels to tomes of Michigan history. It’s both atmospheric and historical as the honey-toned wood seems to invite curiosity. Beyond the books lie the Archives and Special Collections, a nod to the detailed work of Dr. Natalie Dykstra’s biography Chasing Beauty: The Life of Isabella Stewart Gardner. Rows of chairs fill the small room which is soon filled with eager listeners. At 3 pm on a Thursday, this space often lies empty and quiet, but today is different.

Today is for storytelling—for imparting the discovery of Isabella Stewart Gardener.

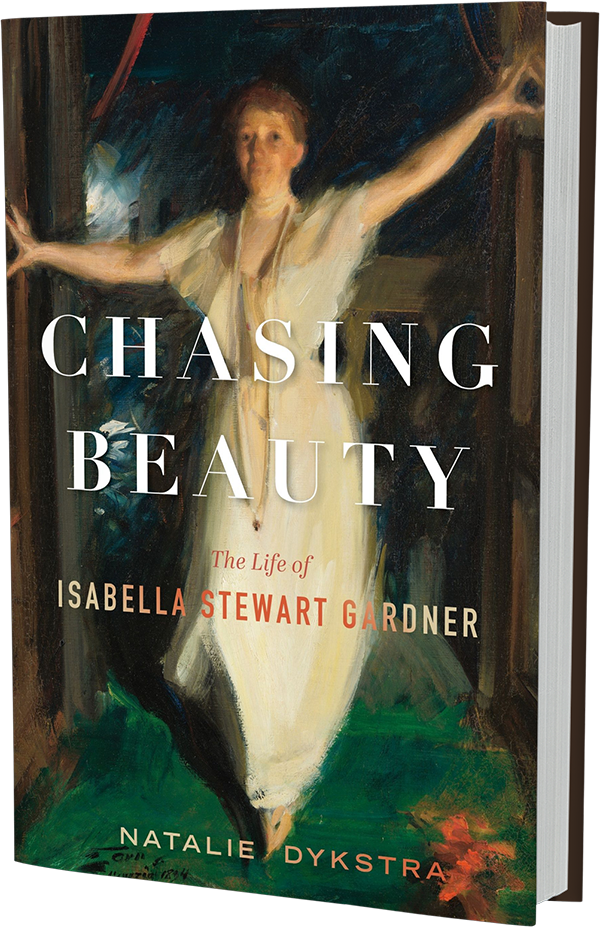

Isabella’s story was brought to life by Natalie Dykstra, an emerita professor and senior research professor at Hope College. In 2018, Dykstra received a Public Scholar Award from the National Endowment for the Humanities which supported the detailed archival work needed to craft Isabella’s story. Dykstra’s research and writing were also supported by the inaugural 2018 Robert and Ina Caro Fellowship sponsored by the Biographers International Organization (BIO).

Dykstra opened the talk by describing biography as a genre and providing a brief recap of Isabella’s life. First, Dykstra explained that biography deals with “a fascination with the past, a love of storytelling, and the intrigue of the archives.” Recalling a Virginia Woolf quote about biography, Dykstra described the work as “something intimate. People are never the sum of our theories about them. Biography is a kind of resurrection of the individual.”

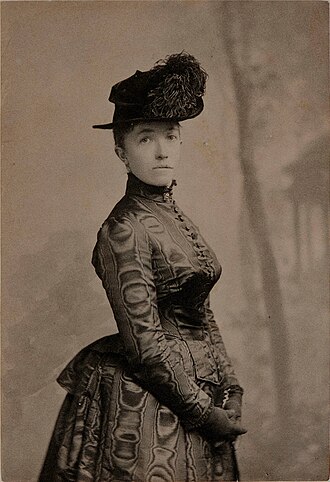

As for Isabella herself, at age sixteen, she moved to Paris where she became friends with Julia Gardner and Helen Waterston. By twenty, she had married Jack Gardner and, by twenty-five, she had lost her first and only son, Jackie. At this point, Isabella began to travel the world—it became her second education. Whilst traveling, she created travel journals and photo albums, training her eye to put artwork together in a narrative—which she would later do in her museum Fenway Court. In the museum, no artwork is isolated—there’s both historical and personal context, as though you’re moving through both place and time

Dykstra faced many challenges throughout the project. Simultaneously, there were too many sources and too few. There was an incredible quantity of material surrounding her later life, but very little about her early life. For example, although the loss of her son was pivotal, there’s almost no record of Isabella grieving her son. Periodically, however, Dykstra experienced the great joy of the biographer. While combing through records in Massachusetts, Dykstra discovered the Waterston diaries, including an entry on December 8, 1856, in which Helen mentions meeting Isabella. In Dykstra’s words, “To find your character in newly discovered sources is a biographer’s dream.”

After introducing Isabella, Dykstra drew attention to the panelists surrounding her—the former Hope students who assisted her in the research process. These students included Hannah Jones ‘21, Aine O’Connor ‘20, Sarah Lundy ‘19, and Melanie Burkhardt ‘18.

After the introduction, the panel discussion began, moderated by Dr. Stephen Maiullo, the Dean of Arts and Humanities. What follows is a transcript of the discussion, edited for length and with a focus on the research process.

How did you get involved in this project?

Burkhardt: I started as a TA for Dr. Dykstra. I remember Dykstra mentioning she had an idea for a new book and that she needed a researcher. So, for the next two years, I worked with her.

Lundy: I worked with the history department already and one day I got a surprise email asking if I wanted to do some research for Dykstra and if I’d like to go to Paris. It was a great experience outside the classroom to work in archives and see what that process looked like in the real world.

O’Connor: I was sitting in Lubbers one day with my feet up and maybe not looking super professional. Dykstra walked in and I put myself together. We ended up talking and I told her, if she ever needed a TA, I’d be it. Well, later, I wanted to do research in Boston so I asked Dykstra. She said ‘How about Paris?’

Jones: I was also working as a TA and had a class with Aine. We got to go to Paris and ended up doing a lot of transcription work–especially on the Waterston diaries.

What were some of the projects you worked on?

Lundy: For the most part, I was looking for day-to-day life. What was the weather like? What did her family do? What classes did she take? Really, it was lovely to dig into her letters, postcards, etc. It gave an image of her as a person and it wasn’t something I typically thought of in the context of archival research. It was getting to know about Isabella and her early years—a piece of her that was less well-known than the museum.

Jones: Aine and I worked on transcribing the Helen Waterston diaries. Her handwriting was okay and she’d sprinkle in a bit of French which was fun. In her writing around age 16/17, Isabella was such a talented writer and it was a beautiful picture of the teenagers together in Paris. Helen described Isabelle as having a passion for ‘jollification.’ We dug into the weather, into Jack Gardner’s financial records… It was fun when the requests came in because we never knew quite what they were for.

Burkhardt: Sometimes it was very hard (and fun) to transcribe Isabella’s letters–sometimes her writing was very slanted. I didn’t go to Paris, but I was able to go to Boston and visit the museum. I spent a day at Harvard at the Houghton Library, transcribing Henry James and TS Elliot. So much of studying English was reading something that someone had already discovered and this was going directly to the source for the first time.

O’Connor: Outside of transcribing, we cheerleaded the book. It’s hard as the writer because it feels like you’re isolated and it was so lovely to step into the process.

Dykstra: I’d bounce ideas off of them. You don’t write books alone–not even close–and I was so fortunate to have people cheering me on.

How did you stay motivated when the research got hard?

Lundy: Research is time-consuming and iterative. Sometimes, you need to take a break and come back later—give yourself that grace. When you’re in a research trip situation, you’re often there because the resources are there. Yes, being in the library is important but the cultural experience of the place–walking the streets–is equally as important. You’d get a sense of being a non-native person and speaker. Back in the US, it’s important to set a schedule and have dedicated research time to work on the project. You needed to figure out what to prioritize and what to come back later.

O’Connor: In Helen’s diary, we had so many red question marks, things we couldn’t read that left gaps in the story. No research happens alone and it was important to be able to work together.

Jones: We’re naturally curious people and had a desire to know more. You’d find a word you didn’t know but, if you kept reading, it might show up again and this time you’d be able to read it. In the research process, failure is inevitable but it’s a time to learn, even to change course. It’s an opportunity to pivot. Working in Paris, Aine and I worked about 5 to 10 hours per week. While there was a timeline, it was also pretty flexible. Working together, one person could talk and one could type, then we could pause when we got stuck.

The documents you worked to transcribe were written in cursive. How important is it to understand cursive when researching?

Lundy: So much of the historical record is written in cursive. Part of the repetitive iterative process was learning those handwritings—the quirks of each person. Correspondence remains incredibly fascinating because the actual handwriting tells you so much about the person.

O’Connor: Yes, transcriptions are important, but you need to know cursive to get to the actual materials. There’s something life-changing about physically holding those sources.

What inspired you (Dykstra) to write the book and how did you get the team on board?

I asked them because I could tell they were interested. They were good students and I knew that. Plus, they were working on Isabella’s teenage years—the same age they were which lent a unique perspective. It’s important to have different generations working together.

It took me 18 months to decide to write her story in the first place. She had so many friends, an enormously important art and historical story, and she also lived for a long time. It was a true story and people are very attached to the museum. You don’t take something like that lightly.

But there were also so many themes of her life that I felt I had something to say about. Her spirituality but also her relationship between heartbreak and beauty and light. She just had this intense curiosity—even at the end of her life when she was paralyzed by a stroke.

She was a remarkable woman and I wanted to live with that character.

In the writing process, how did you (Dykstra) manage the narrative story and the dense historical information that provided its context?

You need the stream–the social context–but you need to follow the fish. Your character should be apparent on every page. The reader needs to feel close to her, to see her alive on the page. Biography is a story—everything else can go in the endnotes. Follow the senses to convey her world. That allows the reader to see through the sentences as well. And it takes practice.

“If I had one piece of advice, it would be to build one good day. Figure out what you need to do and build that day. That’s how books are written. “

Natalie Dykstra