Written by Anna Stowe, Hope College Creative Writing Major and Student Managing Editor for the English Department

On September 11, Winants Auditorium was filled with members of the Holland Community, students, professors, and friends, all gathered to discover the life of Isabella Stewart Gardner. Light filtered through the stained glass windows as the room rumbled with chatter. A few minutes before 6 pm, Dr. Stephen Maiullo, the Dean of Arts and Humanities, opened this year’s Community Summit on Arts and Humanities, a two-day event celebrating the work faculty and students are doing in and outside of the classroom.

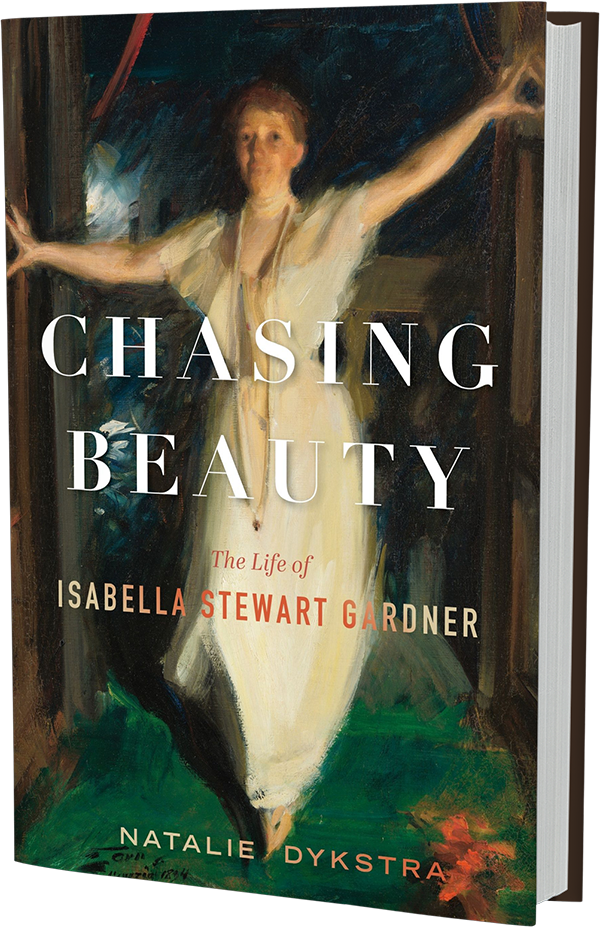

After a brief introduction, author Dana Vanderlugt took the stage, introducing her friend and mentor Dr. Natalie Dykstra. An emerita professor and senior research professor at Hope College, Dykstra influenced several students who later joined her in the research process for Chasing Beauty: The Life of Isabella Stewart Gardner (published March 2024). Praising Dykstra’s research, teaching, and writing process, Vanderlugt stated that “the hallmark of scholarship is a passion for teaching–opening doors and windows for others.” With her shoulder-length gray hair, a colorful scarf tied around her neck, and glasses perched on her nose, Dykstra paints a picture of a brave, curious, wise woman. In Vanderlugt’s words, “She is a keen listener and adept at bringing light and grace into hard things… In the book, Isabella chases beauty, but that’s also what’s done in the writing.”

At last, Dr. Natalie Dykstra took the stage, opening her presentation with a long list of acknowledgements. Although a surprising introduction, Dykstra’s words highlight the fact that research and writing are not done alone. Despite being a fundamentally solitary act, the actual process takes a village.

And then we met Isabella, a New York girl. Dykstra’s passion for Isabelle–or Belle, as she called her–was clear as her eyes lit up and her hands came alive with movement. Passing over much of Isabella’s early life, Dykstra emphasized Isabella’s move to Paris at age 16 where she entered a convent school. Here, Isabella met Julia Gardner and Helen Waterston, whose diaries provided a previously undiscovered connection. It was Helen who first called Isabella a New York girl in an entry dated Dec 8, 1856. In 1860, Julia’s brother, Jack, would become Belle’s husband. Dykstra also mentioned the core of Isabella’s motivation: to create a palace and fill it with beautiful things.

The young couple soon faced tragedy. Isabella’s only child died before reaching his second birthday. Facing the death of her son, Isabella’s grief derailed her. Despite this sorrow, however, Isabella and Jack began to travel the world–visiting Europe, Africa, and Asia. During their travels, Belle filled 28 journals with descriptions, drawings, and anecdotes as if she could put the world on a page.

Interestingly, Isabella began collecting artwork early on–photos reveal the correlation between the Gardner’s home and the eventual museum galleries of Fenway Court. Unfortunately, tragedy struck once more in 1898. Jack Gardner’s death once again marked Isabella’s house of beautiful things with grief. Once again, Isabella found a new purpose–this time by creating Fenway Court, modeled after a Venetian palazzo turned inside out. A testament to her determination, Isabella is recorded as having overseen the project herself, accompanied by her lunch pail.

Today, Fenway Court is known as the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Its halls are filled with a collection of paintings, sculptures, tapestries, furniture, manuscripts, rare books, and more. Displayed carefully, the museum is more than a collection of objects–it is Isabella’s way of bringing the world to America.

Such a clear recounting of Isabella’s life may rest on a page conveniently, but crafting her story was not without difficulty. Dykstra emphasized this point, explaining that there was very little documentation of Isabella’s early years, but a vast quantity of writings surrounding her later life. In Dykstra’s words, “While I wrote, there was the feeling of weaving her story from gossamer threads, but it was all important. Early accounts of Isabella didn’t seem to match the soulfulness of her creation, its sweep, its seeming spiritual claim… That’s when I realized you had Isabella when you had the museum.” Before she died in 1924, Isabella stipulated in her will that the museum could not be changed–it had to remain exactly as she created it.

Despite facing immense loss, Isabella Stewart Gardner never stopped chasing beauty. Even in the cover image of Dykstra’s book, Isabella’s arms are flung open to the world and to experience; “It was as if she said, ‘Come out all of you, this is too beautiful to miss.’ She chased beauty throughout the heartbreak of her early life.”

Following Dykstra’s introduction of Isabella, Vanderlugt joined her on the stage, settling into chairs facing each other for the interview portion of the event.

What gave you the bravery to write it and drove you to tell the story?

People have such strong feelings about the museum and such strong attachments to it–deep experiences. Belle was in her 60s when the museum opened and lived another 20 years. There had to be a better story than what had been said up to that point. At the same time, if she had told us what it meant, everything would have turned back to her. Then I realized she didn’t want to insert herself between the visitor and the art. She wanted individuals to chase beauty themselves. She deserved a story that brought her alive. And there was the spiritual side–something I felt I had something to say about. Most people focus on the collection itself–which does make sense, but it’s almost like she got overshadowed by her own accomplishment. And then there’s the theft–13 pieces were stolen and it’s an ongoing investigation. That overshadowed the museum too. It created a double shadow.

How did the experience of writing compare to the experience of teaching? How do they intersect?

When I was writing well, I was teaching better. When I was teaching well, I was writing better. It was a synergy–they fed off each other. I mean, it is about audience and storytelling and surprise but in the classroom it’s such a human thing. You never know quite what’s going to happen and you end up going to a new place together–both in the classroom and in writing. I love the element of surprise–it’s life, both on the page and in the classroom.

You talked about the grief, the tragedy, and the joy. What brought you joy in the process of writing but also now?

While writing, I was very much at my desk. It took five years to get this done. When you’re really in it, it’s not lonely because these people come alive–so alive that it’s almost too many people in my head. At the same time, sometimes it’s not going well and that’s really hard. There’s also the readers–I get emails in the middle of the night saying ‘I just had to tell you…’ and I remember what the writing is for. I was also scared that I would fundamentally change the perception of the museum itself–but, thankfully, that didn’t happen. So yes, it’s just so nice to have readers.

The museum remains the same every single time–Isabella stipulated that. Is that part of the power of the museum or does that detract? What is the effect of that?

Well, she stipulates that nothing can be moved in her will. She hired the best architectural photographer and attached those photos to the will so that they literally couldn’t be changed unless you went to court and fought. She didn’t want to just bring the painting back but she wanted to bring the experience of seeing the paint where it was. She knew how to display these objects to their greatest effect. It was a struggle to figure out what paintings and installations to talk about and how those could be used to tell the story. Now though, it draws you closer to Isabella. It gives intent–it’s like a scrapbook. And once you have intent, you have a through-line, you have a storyline.

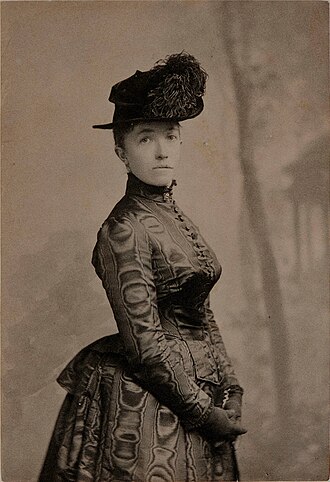

Throughout this event, Dykstra emphasized her reading, research, and writing process. She showed letters, travel journals, images of the gallery, even photos of Isabella. These served to flesh out Isabella’s character, give her flesh and blood. Reviews for Chasing Beauty are accurate: “…in the dazzling Chasing Beauty, Dykstra found a way into Gardner’s life through diligent research that uncovered traces of the woman in the worlds she inhabited. Evocative and absorbing….” —Washington Independent Book Review