Teaching Rap as Poetry

by Pablo Peschiera

In my poetry classes, I often teach the basic structures of poetic rhythms through rap music. I use rap songs from artists like Public Enemy, Run DMC, Fu Schnickens, Queen Latifah, Eminem, LL Cool J, Lizzo, Frank Ocean, Kendrick Lamar and many others. This no accident. Rap and poetry go together like Salt-N-Pepa.

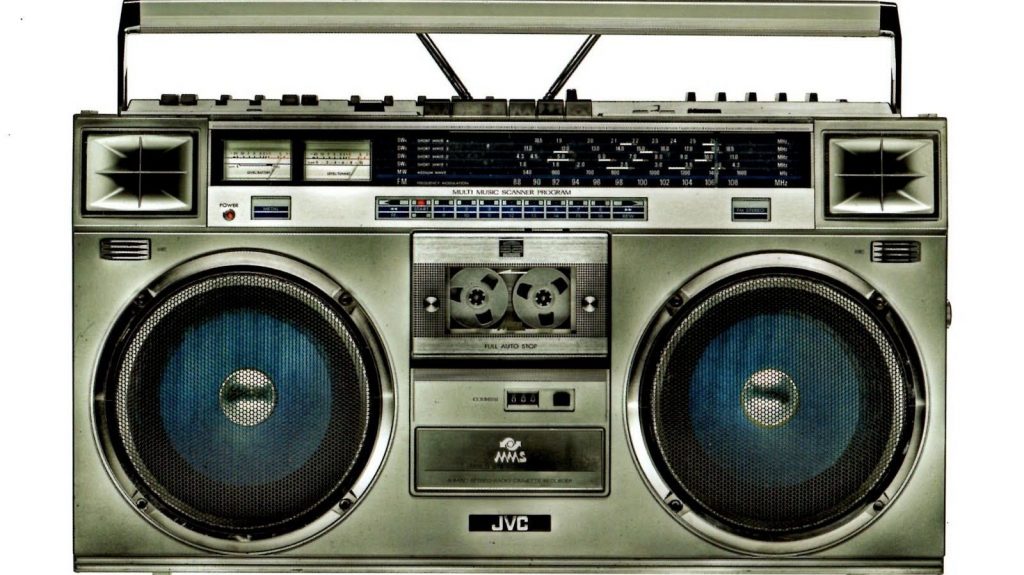

I first heard Grand Master Melle Mel and the Furious Five in the cafeteria at Hackett Catholic High School. I was 15, at the spaghetti dinner for the JV football team, and the Henagar brothers had their boom box on the table. “Music for crushing skulls,” one of them said, and I heard the MC King Lou rap “K is for Kool, running through my veins/I got ice water blood, so I show no shame.” I was hooked.

I’d been a suburban b-boy for a couple of years, break dancing in the halls at school, at school dances across the city, and at a charity fair or two. I’d even been paid to do it—once. I’d seen the movies Breakin’ and Beat Street and loved them. And since these movies used hip-hop and rap as a background to the dancing, rap became a part of my social world. Break dancing hasn’t stuck with me—I mean, how could it?—but rap grew into the most popular genre of contemporary music in the world, and it never left my body and mind.

Rap took off nationally in the early 1980s. The Sugar Hill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” charmed me to no end. Run DMC helped me think about the powers of community and neighborhood in ways a boy in suburban Michigan would never experience. Salt-N-Pepa exposed me to a new kind of strong female power. Public Enemy schooled me in anger and frustration at systemic racism. I wanted to understand all of it.

Witty, charming, silly, and angry, the lyrics that rappers created seemed to roll out of their mouths. Some were deeply experimental and intelligent, like Fu Schickens. Some were sweet and funny, like DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince. All were highly creative, and oozed youthful exuberance.

As a boy and young man, I stuttered when I spoke, sometimes terribly. Speaking in front of people, especially strangers, put me into a panic. I avoided it, hard. But rappers spoke in tight, improvisational patterns, eloquent and strong. I wanted that power, and rap showed me a path to achieving it.

Poetry had an ascendant respect in my family, and rap was my first poetry. I began writing poetry and rap at around the same time, in the 80s, but because I stuttered I never saw myself as a rapper. I had to learn to work with language in the quiet of a white page and a solitary room.

Over time, my poems became less auditory, shed their rhyme and tight rhythms controlled by the 4/4 bar structure of a rap song. But rap and poetry can never be fully separated—they are siblings, sisters in song, singing in their own overlapping spheres of influence. And you don’t have to love rap music to see the connections—it’s there in the deep analysis of rap’s poetic structure.

Among the best poets in the world is the rapper MF Doom. MF Doom has the ability to layer chains of sounds in seemingly endless overlapping links. Check out these lines from the second verse of “Rhymes Like Dimes”:

Better rhymes make for better songs, it matters not

If you got a lot of what it takes just to get along

Surrender now or suffer serious setbacks

Got get-back, connects wet-back, get stacks

Even if you gots to get jet-black, head to toe

To get the dough, battle for bottles of Mo’ or ‘dro

This fly flow take practice like Tae Bo with Billy Blanks

“Oh, you’re too kind!” “Really? Thanks!”

That verse goes on for ten more lines. It seems nonsensical, the references coming so fast you almost can’t track them. Rhymes weave across lines, sometimes only at the end of a line, sometimes appearing six times across three lines (lines five to seven). Alliteration—the technique of repeating the sounds at the beginnings of words—appears several times, occasional (line one) or rapid-fire (line three).

Most interested in sound and association, MF Doom filters the world through his imagination and what comes out in his rap is a representation of what his memory can conjure at the moment. His raps are in the best tradition of poetic nonsense, like Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky.” In nonsense poetry, sound structures take over to shape our understanding of the poet’s world. How the words sound is as important (more important?) as what they say; they flow together in a kind of language music.

That is why I love rap, and this kind especially. As a boy and young man—even in college—I could barely string together a spoken phrase. My speech hemmed and hawed, paused at the worst times, and I would lock up, my face twisting, my lips in a struggle to shape the sounds. Those who work and live with me have seen this happen even today in my middle age, especially when I’m tired. My everyday face sometimes feels like a mask about to transform.

But rappers like MF Doom display the transcendence of human speech as artistic expression. Their faces, however hidden, never falter, the muscles of their throats never seem to fail. In their poetries I feel transformed into a person with no limits to my language, no limits in my ability to express myself. I write poetry, but in the back of my creative mind, rap will always be pulling at the levers.