In today’s post[1], Dr. Kendra R. Parker explains the inspiration for her new book, She Bites Back. She offers us a snippet of her book and of her upcoming colloquium presentation on Thursday, February 28 at 3:30 PM in the Fried-Hemenway Auditorium.

I began working on this project in 2011 while a graduate student at Howard University. The idea came from a seminar paper, “Vampirism and Political History in Octavia E. Butler’s Fiction,” and over time it transformed into my dissertation, “Biting Back, Biting Black: Black Female Vampires in Literature and Film” (2014).

In 2016, I began to consider seriously revising the dissertation into a book; I’d been at Hope for three years and encountered a number of Black women students who were navigating misogynoir and the burden of representation. At eighteen, nineteen, and twenty, they should have been exploring their lives through the liberal arts curriculum; instead, they were grappling with being called “oreo,” “ghetto,” “threatening,” and “angry” by their peers, and being silenced, ridiculed, and mocked by their instructors.

They were stereotyped as predators for daring to exist and claim space in a predominantly white institution. They were experiencing what Dr. Koritha Mitchell calls “know-your-place aggression.” I observed them; I listened to them; I created courses for them. I wanted them to hold fast to what they knew deep down—that they were complex beings. But at Hope, they were socialized into thinking that they were flat, one-dimensional.

Such one-dimensionality is not ahistorical. As public intellectuals like Patricia Hill Collins, Angela Davis, Melissa Harris-Perry, bell hooks, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and others have recognized, the flat constructions of Black American women as Mammy, Jezebel, Black Lady, Strong Black Woman, or Angry Black Woman render Black women both hypervisible (always seen) and hyper-invisible (never seen).

But what, you must be asking yourself, does any of this have to do with vampires?

In the mythology of the vampire, the vampire is more than blood-sucker; it is a socially constructed body that becomes a scapegoat for sexist, racist, and homophobic value systems. There are many ways the vampire becomes a scapegoat, but I will give you one: the vampire had the potential to be a political threat—a threat that needs eradicating.

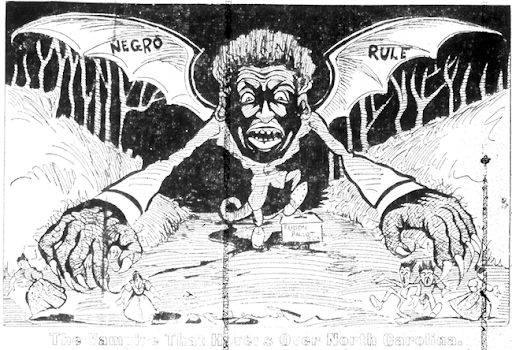

If you replace “the vampire” with “Black women,” this statement remains true. Let’s take the 1898 political cartoon, “The Vampire that Hovers Over North Carolina,”[2] pictured below, as our example.

In this image, a Black male vampire with “Negro Rule” on his wings hovers over white men and women, grabbing at them with his claws. The vampire is stomping on a ballot box. This fear of “Negro Domination,” as Ida B. Wells-Barnett describes it in her 1895 work A Red Record, is just one way Black bodies were coded—and in this case explicitly represented—as vampiric.

In this image, a Black male vampire with “Negro Rule” on his wings hovers over white men and women, grabbing at them with his claws. The vampire is stomping on a ballot box. This fear of “Negro Domination,” as Ida B. Wells-Barnett describes it in her 1895 work A Red Record, is just one way Black bodies were coded—and in this case explicitly represented—as vampiric.

With the ratification of the fifteenth amendment in 1870, which granted Black men the right to vote, the fear of “Negro Domination” or “negro rule” was rampant, so much so that lynching—a systemic tool of terror used to maintain white supremacy—was the norm. These fears, as the cartoon illustrates, became transposed into the political discourse of resistance, hate, and eventual obliteration.

Although this photo depicts a Black male vampire, Black women were, too, imagined and treated as predators when they involved themselves with Black Americans’ advancement efforts. One such example is the burning of Wells-Barnett’s property in 1892, after she denounced lynching and its supposed justifications. The 1918 lynching of Mary Turner, a Black American woman who protested the lynching of her husband, is another example. Walter White, NAACP President, described in detail Mary’s murder:

At the time she was lynched, Mary Turner was in her eighth month of pregnancy [ . . . ] Her ankles were tied together and she was hung to the tree, head downward. Gasoline and oil from the automobiles were thrown on her clothes and while she writhed in agony and a mob howled in glee, a match was applied and her clothes burned from her person. When this had been done and while she was yet alive, a knife, evidently one such as is used in splitting hogs, was taken and the woman’s abdomen was cut open, the unborn babe falling from her womb to the ground . . . and then its head was crushed by a member of the mob with his heel. Hundreds of bullets were then fired into the body of the woman…[3]

White’s description of Mary’s desecrated body, and his emphasis on the use of a hog knife to gut Mary, is intended to highlight the ways the white elites devalued her. As per the description, the white mob did not consider Mary human; they viewed and treated her like an animal simply because she dared to bring her husband’s killers to justice. This group of men did not appreciate Mary’s questioning. Their use of the hog knife to gut her was to make a point. In murdering Mary, these white elites reemphasized their importance as social, political, and economic leaders. Through Mary’s death, they demonstrated that they were not comfortable with a Black woman challenging their system.

Mary Turner functioned as a political threat by questioning, challenging, and pushing back against white supremacy. As a result, she was stopped by whatever sinister means necessary. Ultimately, “The Vampire That Hovers Over North Carolina” demonstrates the danger of codifying Blackness (and, implicitly, Black femaleness) as something to be feared and eradicated.

Though my students were not physically harmed while at Hope (at least not to my knowledge), they did experience ostracism and marginalization any time they dared challenge systems that benefitted whiteness. One student, a few weeks before she was to graduate in May 2018, was called “subhuman” by a member of the Hope Academy of Senior Professionals (HASP). This student was, simply by existing, considered a threat.

I began writing this project as a requirement to finish my doctoral degree, but I wanted to finish this project for my Black women students. It was my way to affirm their Blackness, their humanity, in the face of the misogynoir they collectively experienced on Hope’s campus.

Intrigued? Want to learn more? Come to Dr. Parker’s presentation, “She Bites Back: Black Female Vampires in Life and Lit,” on Thursday at 3:30 in Fried-Hemenway Auditorium, located in the Martha Miller Center. She Bites Back was published in 2018, and is available for sale and at libraries.

[1] A portion of this post appears in She Bites Back and has been adapted with the permission of the publisher.

[2] “The Vampire that Hovers Over North Carolina,” News and Observer, Raleigh, NC, September 27, 1898. The 1898 Collection. The Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Accessed April 25, 2018, https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/items/show/2215.

[3] Walter F. White. “The Work of a Mob.” The Crisis, 16, no. 5 (September 1918): 222. https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/workers/civil-rights/crisis/0900-crisis-v16n05-w095.pdf