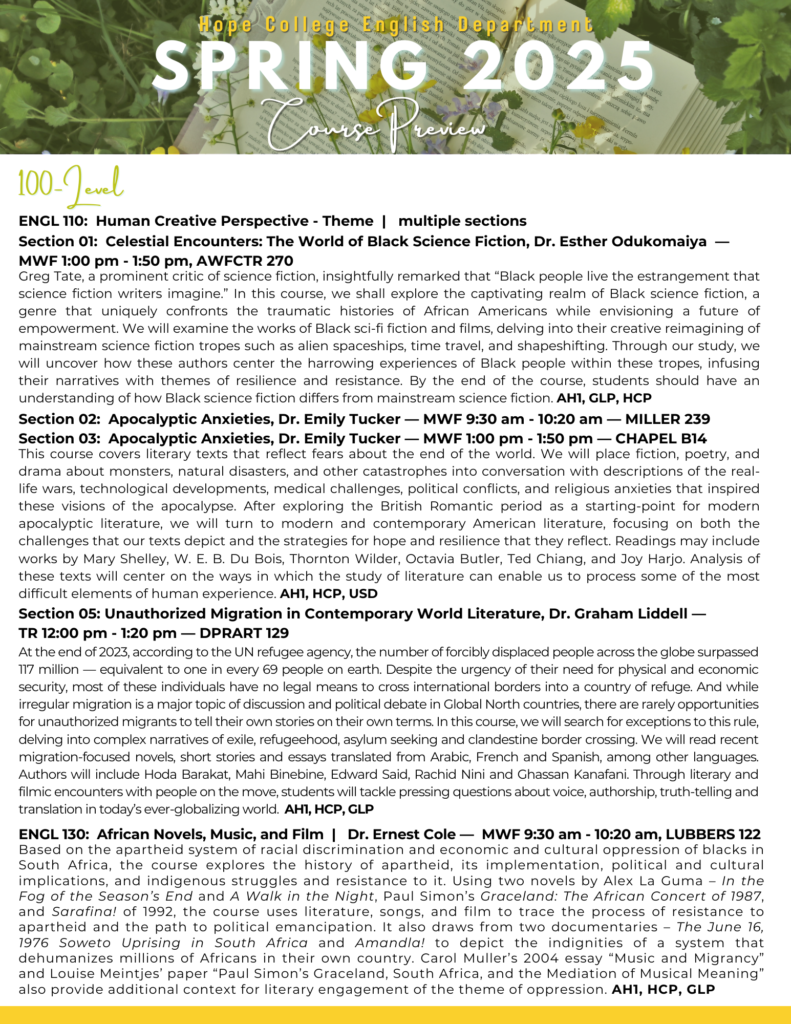

Written by Elsa Kim, Creative Writing and Psychology major at Hope College

The warmly-lit seats of Winants Auditorium steadily fill with students, staff, and faculty. Golden light illuminates the stained glass windows, accentuating the wood paneling of the auditorium. It’s 7 pm on a Monday and everyone here is gathered to hear about the delights and crimes of English grammar. The crowd nestles deeper into their seats, anticipating the start of the lecture, just as Dr. VanEyk walks on stage to introduce our speaker for the evening.

Anne Curzan has worked as a professor of English at the University of Michigan since 2012. Her long string of awards includes the Henry Russel Award for outstanding research and teaching in 2007, the Faculty Recognition Award in 2009, and the John Dewey Award for undergraduate teaching in 2012. Curzan also co-runs a Sunday morning segment on Michigan Public called “That’s What They Say” and has written many books and articles on the English language. She’s even given a TedTalk titled “What makes a word real?”

After welcoming applause from the audience, Anne Curzan walks to the front of the auditorium and introduces her lecture for the night, based on her new book: Says Who? A Kinder, Funner Usage Guide for Everyone Who Cares About Words. Curzan, wearing a beige plaid dress, glances up at the title. “And yes,” she says, turning to challenge us with her stare; “I did use the word ‘Funner.’” The crowd laughs.

Curzan then explains what a historical linguist actually does. She sums it up as “analyzing how we get from Beowulf’s ‘Hwaet! We Gar-Dena in gear-dagum…’ to modern-day texting and the word rizz.” The job of a teacher and linguist, she tells us, is not actually to make sure that students learn correct grammar. Instead, it’s to ensure they have “the largest possible toolbox” to utilize language.

Next, Curzan leads the crowd through an exercise. She reads the sentence “At midnight I ____ into the kitchen” out loud, then challenges us to insert either sneaked or snuck into the blank. When asked for a vote, over half the audience members raise their hands for snuck. The room hums quietly as people discuss in whispers: Which of these words is right? And does that mean the other one is made up? Curzan gives us her own answer. “A word is real if we all know it and understand it.” And although there isn’t a technically correct version, Curzan tells us that snuck—a new and irregular iteration of the original sneaked—has recently become the most well-accepted usage.

After this exercise, Curzan addresses what she calls “our inner grammandos and inner wordies.” A grammando, she explains, is “one who constantly corrects others’ linguistic mistakes.” In contrast, a wordie is defined by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary as “a lover of words.” Curzan tells us that “everyone has an inner grammando and an inner wordie.” In fact, we need the two to help balance each other out. And while some of the prescriptive, grammando rules may be helpful to follow, others were never actually true in the first place. For example, the rule “don’t use the passive voice” can be helpful or not depending on the context. Meanwhile: “Don’t start a sentence with and or but? Completely unhelpful—a pernicious myth.” Unfortunately, because of the complex and often misunderstood rules of English, many students feel stupid for not understanding language rather than curating an interest in its changes. “A lot of our education drills the fun out of language,” Curzan tells us sadly.

Curzan then addresses the natural change of language over time—beginning with the slow death of whom. “Whom,” Curzan sighs, “has been trying to die for at least three hundred years… so it will die.” She then lists other recent language changes, such as the singular use of they, the increase of auxiliary-like verbs (hafta, wanna, gonna), and new punctuation conventions for texting. “Tell me if I have this right,” Curzan says, gathering her memory. She then proceeds to (correctly) define the different meanings of the word okay over text. Plain old okay is neutral, it means exactly what it says. In contrast, okay with a period takes on a more serious or angry tone, while ellipses make it skeptical or hesitant.

Finally, Curzan ends by saying that she hopes we can “adapt the mentality of a birder” when approaching language. “Birders,” she notes, “are curious when they see a new bird—they wonder where it came from and how it adapted—they don’t instantly want to kill it.”

As the evening draws to a close, Curzan takes the time to answer a couple of audience questions. Her thoughtful responses highlight the kind approach she takes toward both language and people. She emphasizes the fact that “while intention matters, reception also matters.” Curzan herself has changed a lot of her own language to be more inclusive for everyone—despite not having any personal problems with controversial phrases such as “you guys.” Even in a field with so much room to become cold and binary, Curzan manages to find warmth for others. Her approach to language can be summed up in her final takeaway: “We can care deeply about language and still be kind to each other.”