Our second generation in Homegoing begins splitting these stories between North America and Africa. In this section, we meet Quey, the son of Effia and James Collins, and we meet Ness, the daughter of Esi and an unknown father. The split in these stories also means the background to these stories requires a bit of knowledge of both West African and American history and traditions.

Here are some things I had questions about that might help you gain insight into these two stories (but no spoilers)!

Fufu

Homegoing mentions fufu in this section, and it sounded familiar to me, but I wasn’t sure what it was. Fufu, also spelled foofoo, foufou, or ‘fufuo, comes from a Twi word that means “to mash or mix,” which is pretty accurate to how people make it!

The Akan people traditionally made it with cassava root, yams, or other various starchy ingredients, depending on what was available when and where people made it. The starch is heated with a bit of water and then pounded with a pestle and mortar until it reaches a doughy consistency. While I haven’t had the opportunity to try it, it is said to taste somewhat like a mix between regular mashed potatoes and sweet potatoes. Because of its mild taste, it is often paired with a stew or soup. To eat fufu, you scoop up a bit and roll it into a small ball. Then after you make a slight indentation with your thumb, you use that ball to scoop up whatever soup or stew you have chosen to eat with it. Instead of chewing on fufu, you just swallow it!

There are several variations of fufu today, partially because it traveled with slavery to places like the Caribbean, where the recipe changed based on what was available to the people there. While the nutritional value changed with what ingredients were used, it was usually a food high in calories and carbs, providing lots of energy and nutrition in smaller portions.

If you are interested in making fufu yourself, here is a recipe for yam fufu to try!

Matrilineal Society

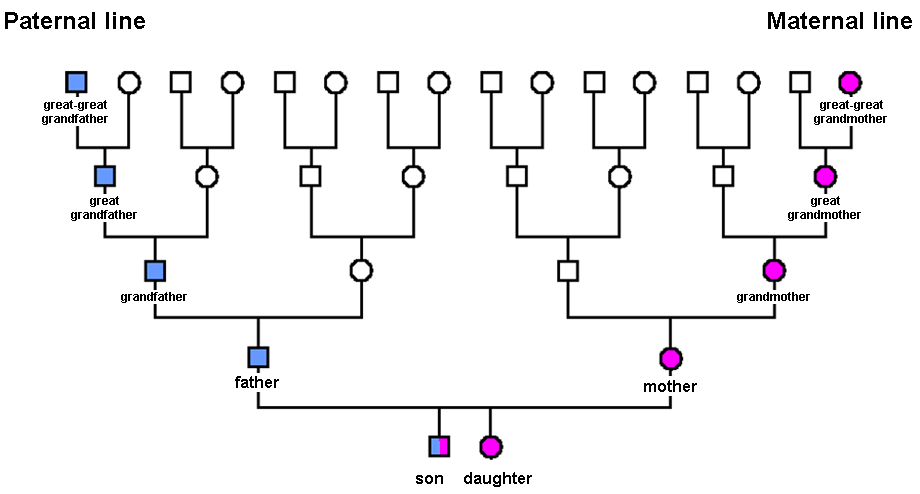

In Western culture, we might be more familiar with a patrilineal view of our families. Patrilineal descent means property, titles, and last names transfer from the father to the children. Throughout history, we see examples ranging from personal items to finances to whole companies or kingdoms handed down from the father to the (usually) oldest son. While we might still get things like our last name from our fathers, we are more used to a bilateral society where both sides of your family are important to you.

In Akan tradition, however, this is not the case. The Akan people live in an area south of the equator in Africa, also sometimes known as the matrilineal belt. Their beliefs and traditions follow a matrilineal system where inheritance and family follow the women more than the men. If you want more examples of these differences, check out this article, “Patrilineal vs. Matrilineal Succession.“

Because it was a polygamous society, it was customary for each man to have several wives. As the children grew up, they were associated with their mothers instead of their fathers because it helped narrow down what section of the family they were really from. Matrilineal succession doesn’t mean that they had a matriarchy where the women ruled over men, but that in family matters, your mother and her family are more important than your father and his family.

There is also a belief that you come from your mother’s flesh but only your father’s spirit. While fathers were still an essential part of your life, they believed that your mother’s family was closer to you than your father’s. Because of this, uncles and nephews were seen as a closer male bond than fathers and sons. According to tradition, if you were an Akan man, your priority would be for your nephew, who is your flesh, rather than your son, who is only related to you by spirit.

If you are still a bit confused or want a deeper look into how matrilineal society works, check out this video, Introduction to Matrilineal Descent, that goes more in depth into how this system works.

Ways of Control

When you think of slave owners keeping power over their slaves, you might think of things like whippings, overseers, or other violent, physical ways to keep their spirits down. However, many slave owners also figured out that there were many different ways to keep slaves under control, like controlling food or water portions, religious ceremonies, creating or encouraging divides through class systems among the enslaved people, and creating a reward system where the more quiet, hard-working slaves got better living conditions and some slight freedoms.

Two other methods plantation owners used to try to keep power over their slaves were marriages among their slaves and taking away their culture. They believed that if they married off their men, they would be less likely to rebel or run away because of their families. Marriages among the slaves were also convenient, not just for control but for saving them money. Buying new slaves was expensive, but if they had more being born on their plantations, it was more free labor coming up. Because of this, some plantation owners even offered freedom to enslaved women who could produce 15 children for them. In some places, female slaves were married off and expected to have children around the age of 13. If, for some reason, they didn’t, they were often punished or sold. Once slaves had a spouse or children, the plantation owners could use them as leverage against them, and it was much harder for them to attempt to escape to the North.

Restricting culture, and especially language, was also a common practice. Some places were allowed to keep aspects of their culture, but it would change vastly due to American influences or be used as a fear tactic to keep the slaves in line. Language was one of the first things slave owners tried to get rid of because they didn’t want their slaves to be able to communicate without knowing what they were saying in case of talks of rebellion. This turned out to be a bit difficult on big plantations due to the fact that there were constantly new slaves brought in who then helped keep language and cultural practices alive.

Hopefully, you learned something new or found a resource that was interesting to you! If you have any thoughts or questions on the third generation in Homegoing, James and Kojo, leave a comment, and I will try to bring it up in the next discussion!