This past Monday night in Maas Auditorium, 13 bottles of water sat on a long table, each provided for one of the 13 people preparing to speak on an interdisciplinary panel about the Flint water crisis. One container of water, though, was not being consumed, nor would it be. Displayed at the center of the dais, a mason jar filled with water from Flint, Michigan, looking as benign and similar as the water in the other 13 bottles, was about to be examined from political, sociological, psychological, historical, scientific, artistic, ethical, and personal perspectives. Though the water in the jar appeared clear, the water crisis and its fallout and solution can seem anything but that.

Though the water in the jar appeared clear, the water crisis and its fallout and solution can seem anything but that.

Organized and implemented by Dr. Julie Kipp’s women’s and gender studies keystone class, the event gave an opportunity for a large audience to consider what has happened in Flint as well as providing a challenge for all to get involved and do something appropriate within their discipline or interest. The panel, made up of one student, 11 professors, and one president, discussed the very tragic, sometimes complex, and always upsetting issues revolving around the high levels of lead in Flint water and those who drank that water for over a year. Delivering their expertise from their various points of view within a five-minute time limit each, the panel continued to cast light upon light upon light onto a problem that has fallen out of the nation’s glare… for the time being anyway. This communal time of reflection also gave hope for understanding next steps in Flint.

Organized and implemented by Dr. Julie Kipp’s women’s and gender studies keystone class, the event gave an opportunity for a large audience to consider what has happened in Flint as well as providing a challenge for all to get involved and do something appropriate within their discipline or interest. The panel, made up of one student, 11 professors, and one president, discussed the very tragic, sometimes complex, and always upsetting issues revolving around the high levels of lead in Flint water and those who drank that water for over a year. Delivering their expertise from their various points of view within a five-minute time limit each, the panel continued to cast light upon light upon light onto a problem that has fallen out of the nation’s glare… for the time being anyway. This communal time of reflection also gave hope for understanding next steps in Flint.

“When you think about what a liberal arts college does best, it is learning how to think systemically and critically about complex things where the problems simply can’t be understood through a single lens. It requires us to think in the round.”

Speaking from personal experience, sophomore Katlyn Koegel, a Flint native, shared several stories about people she knows from home who are struggling and afraid—a small, thirsty boy who asked for bottled water from her last summer, a woman who may lose her business due negative media attention that has driven customers away, and a pastor who paid a $900 bill for water he was not even using. “What has been most heartbreaking for me is this dichotomy between breaking news and broken structures,” said Koegel. “A lot of facts and individual stories have gone down a chasm between the two.”

Historically speaking, Dr. Fred Johnson, declared that Flint has its proud roots in Native American origins and the founding of a General Motors plant there in 1908. “And many of you may know, it was the site of the 1936-37 GM sit-down strike which basically brought the UAW (United Auto Workers) to prominence, making it a major instrument in the labor movement.” Now, the city’s heritage is being viewed only through a microscope created by this recent history.

“All politics are local.”

Politically speaking, Dr. Annie Dandavati, reminded the audience that “it’s important for all of us to be educated voters. Even though we sometimes feel that our voices are falling on deaf ears, it’s important to know about issues no matter where they originate—in the state capitol, nationally or globally. All politics are local.”

Sociologically speaking, Dr. Aaron Franken and Dr. Debra Swanson showed that race and socio-economic status are key to making sense of what is happening in Flint. “When looking at kids in Flint, here’s some points that are important and highlight social processes for health: One, if socio-economic status is linked to health, and two, decreased educational attainment is a key link to lower socio-economic status, and three, lead poisoning manifests itself in behavioral changes and in cognitive ability changes and thus a link to decreased educational attainment, and, four, sizable portions of residents (in Flint) don’t leave the area – so residential non-migration – then we’re going to have a potential geographic health issue with a very long memory in Flint,” said Franzen.

“This is a demographic of poor, black moms with kids who get no political attention.”

In 2013, the median household income in Flint was about half of that than in the rest of the state. The state median income is $43,000; in Flint it is about $23,000. Approximately 22% have a household income of less than $10,000 a year. Forty-one percent of those living in Flint are below the poverty line, 56% of the population is black, and 75% of the households are single-parent homes. “This is a demographic of poor, black moms with kids who get no political attention,” says Swanson. And yet those women have organized protests at the state capitol in Lansing as well as a movement with Lead Safe America Foundation, bringing attention to the crisis on Twitter with over three million tweets in two hours on February 4, using the hashtag, #StandWithFlint.

Psychologically speaking, Dr. Carrie Bredow offered one good news/bad news scenario: “We know that certain things can ameliorate some of the effects of lead poisoning (such as behavioral and cognitive disorders) though it’s not reversible. But based on the research, through things like good nutrition, having high-quality early childhood education and intervention, and consistent medical care, the level of its effects can be influenced. But these are the same things that children in Flint don’t have access to. So this is something that needs to be poured into in terms of how we stop this from affecting people in Flint inter-generationally.”

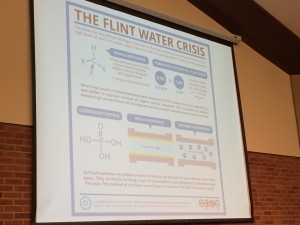

Scientifically speaking, Dr. Joanne Stewart and Dr. Graham Peaslee explained how lead got into the Flint water supply in the first place. “When they switched from (using) Lake Huron water to Flint River water (to save the city money), they had no corrosion plan in place (to keep the pipes from leeching lead into the water). That was one of the real shocking things that happened,” said Stewart. “It depends on which house you’re in (when looking at lead levels),” added Peaslee. “Some people have PVC pipes and no lead, others have lead and more lead in their pipes. It depends house to house what the effect was.”

“It’s comforting to suppose only terrifically terrible or malicious people can be responsible for these things but often it is only ordinary, everyday vice that leads to great evil.”

Morally speaking, Dr. Heidi Giannini enlightened with this: “One thing I think the Flint water crisis illustrates and what our response to it should bear in mind is that it is very hard to be good. However, that is no excuse for failing. The crisis in Flint illustrates at least one way it is hard to be good: we form bad habits (like laziness or self-interest) because most of the time they seem like they are not that big of a deal. When we foster these ordinary, run-of-the-mill bad habits, we foster the opportunity for great evil. We like to think that there is extraordinary vice underlying the horrible moral wrongs of what happened in Flint. It’s comforting to suppose only terrifically terrible or malicious people can be responsible for these things but often it is only ordinary, everyday vice that leads to great evil.”

Dr. Charles Green addressed environmental racism, citing evidence that shows more middle-class black families live in polluted areas than poor white families do. “Let me be clear: race is a real factor here… Black kids are three times more likely than white kids to have asthma (due to living in areas with poor air quality) and four times more likely to die from it. The environmental problems that we have addressed in this country over the last 30-40 years have largely benefitting the white population, and the environmental problems we have not addressed have largely impacted people of color.”

“We have to listen. We have to let our neighbors (in Flint) know that we’re here, not to own or claim the crisis as our own but rather to try to understand it.”

From an artistic standpoint, Rob Kenagy and Dr. Katherine Sullivan revealed how art and activism is giving people a news lens through which to view Flint. “The slam poetry coming out of Flint is hot…It’s important to remember that that art is made by real people,” said Kenagy, “and it’s just not something you can click past. There is a real voice behind it. We as readers have a responsibility (to hear it and see it), especially those of us from privileged spaces. We have to actually accept the trauma and invite it into our lives. We have to listen. We have to let our neighbors (in Flint) know that we’re here, not to own or claim the crisis as our own but rather to try to understand it.” Poetry and art is yet another way to do just that.

Finally, President John Knapp summed up the event this way: “Big problems don’t lend themselves to simple, small solutions. What I’ve really appreciated about this evening as I’ve listened to my colleagues here is that we’ve not only examined this problem from the perspective of art, philosophy, poetry, but also sociology, history, and political science. We’ve talked about biological and medical concerns; we’ve talked about psychological matters and even got into chemistry. Every one of those is important, and more, to really understand the nature of the problem. And what I’ve described is what we are about in the liberal arts at Hope. When you think about what a liberal arts college does best, it is learning how to think systemically and critically about complex things where the problems simply can’t be understood through a single lens. It requires us to think in the round.”