Inside a box waiting for her on a front porch, senior Autumn Balamucki was about to pick up history.

She would eventually receive a newfound skill and appreciation, too.

In the summer of 2020, unexpectedly back early from an off-campus study semester in Peru due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Balamucki signed on as an intern with the Joint Archives of Holland to conduct research on the Holland-area veterans of the Spanish-American War.

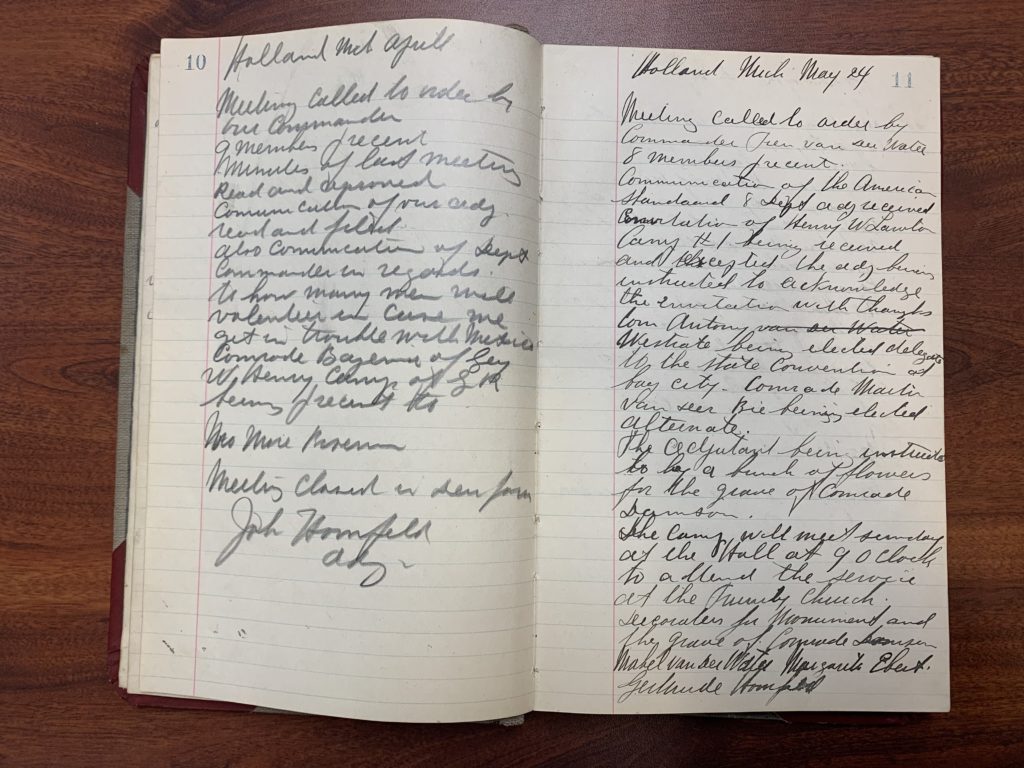

The box she retrieved outside of Hope archivist Geoffrey Reynolds’ home last spring contained copies of 28 years’ worth of the monthly minutes from the veterans’ two-hour-ish-long meetings.

“When I arrived, I had no idea what I was getting myself into,” Balamucki remembers. “Geoff just said, ‘I’ll leave photocopies of all of the original documents at my front door.’ This was in May, and we had to make a contactless transfer because of the pandemic. So, I go to pick them up, and I find a box filled to the brim with papers.”

Each one laden with handwriting. In inky cursive.

Most 21st century college students avoid longhand, and the reading of it, with an intense aversion. In fact, they tend to evade it like looking away from the sun.

Nevertheless, Balamucki was determined to read and transcribed massive amounts of early 20th century handwriting for weeks on end from scribes of the United Spanish War Veterans Camp #38.

Twenty-eight years times 12 monthly meetings per year times 2.5 average pages per meeting. Do the math, and you get the magnitude of penmanship she pored over.

Trying to Read What was Written

Actually, it turned out that Balamucki liked it. It became an exercise not only in distinguishing Fs from Ps, but in discerning and admiring the service and struggle of men and their families from a lesser-known war. (The Spanish American War lasted 114 days, from April 21 to August 13, 1898; though it is mostly remembered for Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders.)

That the Holland veterans formed a camp, or club, and left behind decades of notes marking their determination to acquire pensions and parades and acceptance, showed a commitment to not be forgotten.

“It took me a little while to see the very subtle differences from one person’s handwriting to another (over the length of the project),” said Balamucki who has double majors in global studies and history and a minor in Spanish. “But, figuring out that puzzle was really fun for me. That’s why I majored in history. I love putting pieces together and figuring out how they connect.”

The connections that Balamucki uncovered dealt with that 1915 to 1943 time period, for sure, but there was more than that. She found that the century-old experiences of those veterans had an effect on her empathy for them and her understanding of her present as well.

“It so happened that my struggle to adapt with this unique period in our history (in a global pandemic) ended up bringing me closer to a group of people, in another time in history, whose experiences with global change and the necessity to adapt far surpassed mine,” Balamucki wrote in the Joint Archives Quarterly Newsletter last fall.

“Their story begins 122 years ago, in 1898, on the verge of the Spanish-American War, as a group of soldiers whose lives would see a great amount of change and adaptability in the coming years,” she continued in her article. “These soldiers followed the veterans of the Civil War, and preceded the well-known soldiers of World War I. They saw times of war, times of peace, of economic depression and prosperity, of political unity and dissension, and throughout it all they adapted to the changing world around them that the first half of the 20th century brought.”

The Bigger Picture

Reynolds says Balamucki’s ability to see beyond a single snapshot in time to the bigger picture is a credit to her intellect and Hope education. Though the two could not work together in person last summer, Zoom meetings enabled “in-person” interactions when necessary and their separation did not hinder their work. In fact, Balamucki’s ability to dive into the documents, uninterrupted and without distraction, may have been a bonus from her kitchen table at her home in Traverse City, Michigan. It allowed her to not just read history but to feel it, too.

“Autumn recognized the many struggles of those men – financial struggles, sometimes lack of respect, the changing times — and connected it to the struggles she’s endured and the country has endured in the last year,” says Reynolds, the Mary Riepma Ross Director of the Joint Archives of Holland.

“She was able to identify with them. Fred Johnson (associate professor of history at Hope) hopes his students do that all the time. But that’s a tough thing to do, especially for young people to jump back 100 years and identify with what people were going through. Yet I found that Autumn empathized with the people she was reading about and also questioned, ‘What does that mean to me today, why is this important to now?’”

When Balamucki finished her project three months later, her transcription resulted in 169 typewritten pages in single-spaced, 11-point New Times Roman font. While the tangible results of her work now show up on clean, easy-to-read sheets of paper, the intangible aftermath is the ability to recognize that history is always about people.

This time that lesson was imparted thanks to the (perceived) dreaded yet beautiful reading of handwriting.

“I’m not gonna lie, I was so excited when I finished, but I was torn, too,” she says. “I was shocked at how close I felt to these people. . . I think the fact that what I was reading was personally handwritten hit me differently. I do think that I had a little bit more of a connection than if it had been typed out or explained to me. ”

—

Read more about all of Autumn Balamucki’s research in the Joint Archives Quarterly Fall Newsletter: The Trials of Transcriptions: A Look Into the United Spanish War Veterans of Holland, Michigan