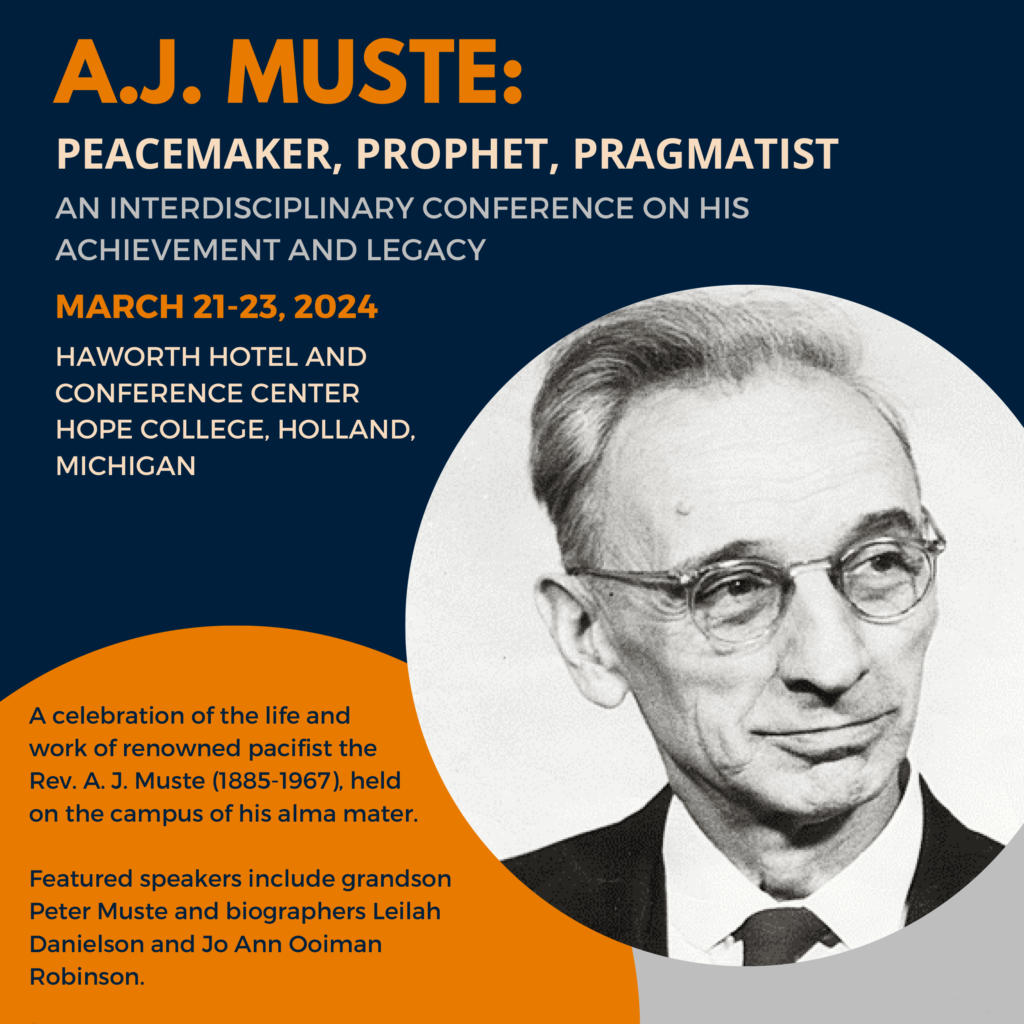

In March 2023, Hope College hosted an interdisciplinary conference on the life, work, and legacy of Hope graduate A.J. Muste (1905). One of the speakers was Peter Muste, A.J. Muste’s grandson, who gave a talk titled, “A.J. Muste and ‘Gandhian’ Nonviolence in a Modern Context.” It was an insightful lecture on how A.J. Muste would approach injustice in the world today, as well as what individuals can do today to bring about peace through positive change.

In approaching this topic, Peter Muste also noted his unique perspective on A.J. Muste, explaining that he, compared to most of the audience composed of Muste scholars and students of Muste’s work, perhaps knew less about A.J.’s role as a public figure and activist, having understood him more as a grandfather and mentor. So, he encouraged the audience to view his reflections through the lens of that role and as a personal reflection or meditation. But, as a former board chair for the A.J. Muste Foundation for Peace and Justice, he provided sage insights into A.J. Muste’s legacy and how it speaks to current nonviolent paths to justice, truth, and freedom.

As students, we sometimes struggle with knowing how to enter into complex conversations related to peace and justice issues. Peter Muste helpfully offered four clear recommendations on where to begin: 1) understand the economic components of injustice and conflict within our world, 2) do not underestimate the power of coalitions and grassroots movements within nonviolent spheres of protest, 3) reconnect with the working class, as they are the key to major changes within the political and social arenas, and 4) always try to maintain collaborative dialogue with those who oppose you in order to ensure human dignity and respect.

Building on this framework, Peter Muste set the tone for the rest of his talk by quoting his late grandfather, who once said: “If I can’t love Hitler, I cannot love at all.” This controversial phrase encapsulated the radical path of nonviolence and pacifism that A.J. Muste followed. In the current political climate, Peter Muste offered this statement and its significance as something activists who are trying to change in the world today need to consider in their work, especially in terms of how it can shape our understanding of and position towards those we might consider “others.” In the era of polarization and partisanship that the United States continues to sink deeper into, he suggested that there are critical issues that can unite pacifists and nonviolent activists and help them learn to communicate effectively and empathize with those on the right. The modern world faces challenges with peaceful activism, he said, because we often lose sight of creating democratic spaces where all can speak their mind. Peter Muste stressed that in order to honor A.J. Muste’s efforts we must remember to respect intricacies and interconnectedness of different issues in order to promote justice for all.

He specifically discussed how this pertains to the labor movement. He pointed out that politicians on the right often use fear and distraction as tactics to keep working class people from realizing that their institutions are not properly serving them. He also noted that pacifists and those on the left frequently undermine their arguments and potential for garnering wider support by failing to empathize with the fear that drives much of the larger resistance to change. In light of this, he focused his on a call to unity across partisan divides, reminiscent of his grandfather’s attempts to unite the left and synthesize efforts between communists and democratic socialists. He asserted, following his grandfather, that affirming the inherent dignity and humanity of all people requires recognition — even of those who perpetuate injustice. Furthermore, Peter Muste affirmed that the only path forward is one in which pacifists engage those whom we have deemed the “other.”

One thing that we have learned about A.J. Muste was how he valued collaboration.

After the event, we asked Peter Muste and his brother, who was also in attendance: How are young adults in this world supposed to use nonviolence to fight the many social, political, and economic challenges when there is no true “Gandhian” leader to show us the way? And how are we supposed to create meaningful connections and dialogue with those who think and believe differently than us when we have grown up in a deeply polarized society?

Their response was simple and had two major components. The first was that we have to understand the difference between leaders and leadership, realizing that we must be able to create our own groups and solutions when there is a leadership void. The second was that we must value creativity in our solutions, flexibility in our opinions and actions, and stay committed to the practice of nonviolence and peace.

One thing that we have learned about A.J. Muste was how he valued collaboration. In fact, he would often intentionally choose to work with those with differing opinions or objectives. By listening to and learning from others, groups and movements that seem fundamentally opposed at first glance could find common ground and work together. When we asked Peter Muste about the potential for having conversations with those who view their differences as issues of fundamental morality rather than opposing perspectives, he explained that it starts with building common ground — a foundation of shared interests that humanize each other. He added that it is from these relationships that productive conversation can begin to have a real impact.

So, we see Peter Muste’s interpretation of his grandfather’s legacy as critical. Public conversations on divisive topics often happen within frameworks that convince people on various sides that the other side is evil and immoral and thus not able to be understood, reckoned with, convinced of another perspective, or even acknowledged. But the pursuit of justice requires those from the opposing sides of many issues to engage not as enemies but following A.J. Muste’s example of interacting with one another as whole people with complex perspectives. For Muste, the activist’s role in this is to actively participate in nonviolence and to strategize and organize accordingly.

—

Avery Rant is a sophomore at Hope College and is a Sociology and Social Work major with a Peace and Justice minor.

Cassie Morse is a junior at Hope College studying Psychology and minoring in Peace and Justice. She is passionate about the intersection of personal growth and the societal/systemic issues that can both complicate and aid in this quest.

—

Read Peter Muste’s talk, “Applying A.J. Muste’s Ideas on Social Change in a Modern Context,” as published by the A.J. Muste Foundation for Peace + Justice.

Very profound and well written. As we near a presidential election, candidates

should read and follow the advice of Muste.

Barbara Timby