Southern Germany, Freiburg included, has been a stronghold of German Catholic Christianity for over 1,700 years, and especially after Charlemagne (742-814 AD) united Germany and France into the Holy Roman Empire under the auspices of the Pope. Even after the Reformation, the south stayed true to the Roman pontiff. In Freiburg, this history has a physical presence: construction of the Freiburg Cathedral of Our Lady (known colloquially as the “Münster”) began as early as 1120 AD, though the original building was much smaller than today’s impressive red, Gothic masterpiece. Even after bombings during both World Wars, the Münster is 90% original- even the stained glass windows date back to the 1400s, when local trade guilds funded their construction.

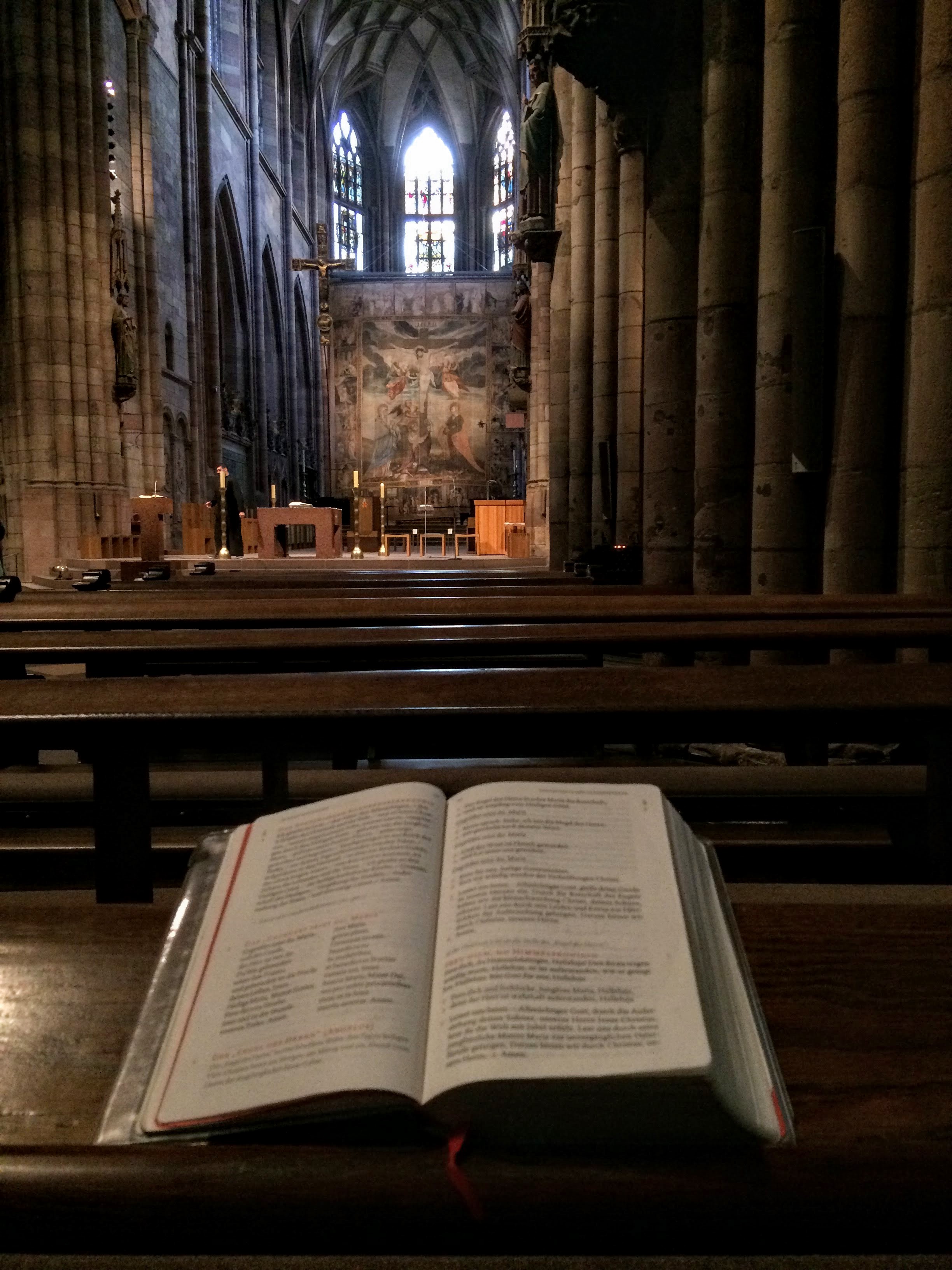

When you walk into the dim, cool interior of the Münster, it’s like you’ve been transported back in time. People light votive candles, pray in pews, and worship in much the same way that they have been for a thousand years. The continuity is striking. Compared to America, where everything is mostly 300 years old or younger, the Christian in Germany has a more tangible sense of timelessness.

Germany has nowhere near the religious diversity that the U.S. has. About 55% of the German population identifies as Christian, and that number is pretty evenly split between Catholics and Lutherans: to an extent, it seems that groups besides these two main ones aren’t noticed by the public at large.

It can be difficult for me to try to explain to Germans what it’s like in America or at Hope with so many different denominations, because the language doesn’t avail itself to subtleties. I believe the large absence of other denominations is because of Europe’s tradition of national churches- after the Reformation got the ball rolling, kingdoms in Northern Europe created national churches under the authority of the monarchy. Examples of this would be the Church of England, the Church of Sweden, the Church of Scotland, the Dutch Reformed Church, and the Lutheran Church in Germany. Because these were associated with a specific European nation, they didn’t spread into other European nations, whereas colonies on other continents were “fair game” for missionary work and pilgrims.

Another unique feature of the religious landscape in Germany is their separation of Church and State- or lack thereof. The strongest political party (both historically since the founding of the Bundesrepublik after WWII and currently, though they’ve weakened significantly in the past couple decades) is the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), of which Chancellor Angela Merkel is the chairwoman. While today the CDU has backed away from being overtly Christian in favor of plurality, its foundations and worldview are still Christian. Interestingly, the CDU (and economists from Freiburg University) are responsible for the current prevailing economic theory and the modern economics system: the “social market economy,” which they like to call “caring capitalism”. A great effort is made to insist that this system isn’t socialist or communist, because the government does not control the economy, but rather regulates the private sector to ensure that people are treated fairly. “Treating people fairly,” however, may often look somewhat socialist to Americans, but Germans are quick to correct you that these policies of wealth-redistribution, mandatory state-run health insurance, and regulations regarding the dismissal of employees are social, not socialist. This leads to further linguistic confusion: when Americans talk about “social issues,” we mean things like LGBT+ issues, race relations, religious liberty controversies, etc., whereas Germans consider “social issues” to mean unemployment assistance, welfare programs, Social Security pension programs, etc. The Christian element in German politics has translated into a government that concerns itself that the “downs” in life don’t destroy people, that no one has to live in inhumane conditions, and that creation is protected.

The Christian heritage of Freiburg is also obvious in day-to-day life. The Munster has been the center of the city for centuries, and it’s Gothic spire is considered the symbol of Freiburg. The skyline would be incomplete without it!

Many doors in Germany have the same little chalk inscriptions on them. There’s a German tradition where every year on the Feast of the Epiphany on January 6th (also called the Twelfth Day of Christmas or Three Kings Day), priests go around blessing homes for the New Year. The letters written have two meanings: one is the initials of the three kings who came to honor the Baby Jesus (Caspar, Melchior, and Balthazar), and the second is the Latin phrase “Christus mansionem benedicat”, which means “Christ bless this house.” The numbers are the years since the birth of Jesus (aka the current year), and the crosses are a symbol of Christ.

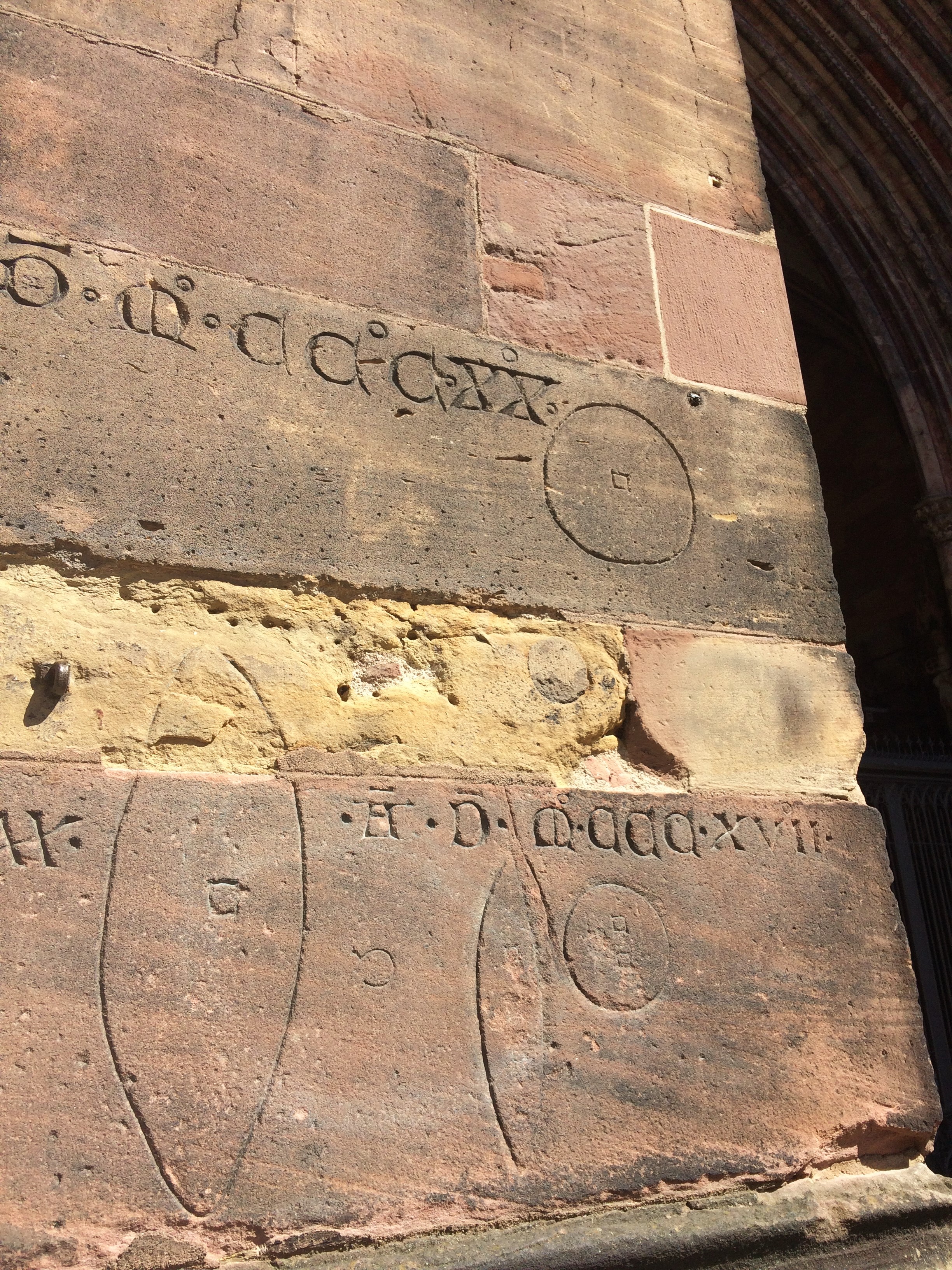

Every day of the week except Sunday, an outdoor market sets up around the Munster selling all kinds of things- flowers, produce, candles, bread, sausage, and toys are just some of what you can find. This market has been going on since 1120, and there’s still carvings in the doorway of the Munster that show the standard measurements used by the medievals. Having this market was a big deal for Freiburg in the early days and helped to develop the city as a center for trade- and all of it is centered around the Munster.

Public holidays in Germany are more frequently also Christian holidays. Christmas Eve, Christmas, Good Friday, Easter Monday, the Ascension of Christ, Pentacost, Corpus Christi, and All Saint’s Day are all public holidays. On these holidays and on every Sunday, most businesses close and public transportation runs on reduced schedules. If you need to go grocery shopping on a Sunday, you’re basically out of luck, even in the city!

A further entanglement between Church and State is the “Church Tax”. Every month, Christian citizens have a tithe automatically deducted by the government from their paycheck to go to a federally recognized religious congregation. In Germany, the Church and the government have historically had a fairly close relationship, in which both mutually relied upon and benefited from each other’s administrative structures- the Church Tax is simply a continuation of this symbiosis.

Because of the Church Tax, churches in Germany are relatively well funded and rich compared to America. However, secularism is on the rise in Germany, especially in the former socialist German Democratic Republic (East Germany), where Christianity was discouraged by the government. Slightly over 50% of German youths aren’t religious, and it shows when I go to church here- most people are rather elderly, the pews aren’t full, and there’s not as many families with children as I see in America.

Nevertheless, I have been able to find ways to get involved with the local faith community here in Freiburg. I joined one of the 5 choirs at the Munster, which has helped me meet a lot of people. The age range is really broad (about 20 to 65), but everyone is very friendly and nice, so I don’t feel out of place. (I’m planning a post specifically about my involvement in the choir later.)

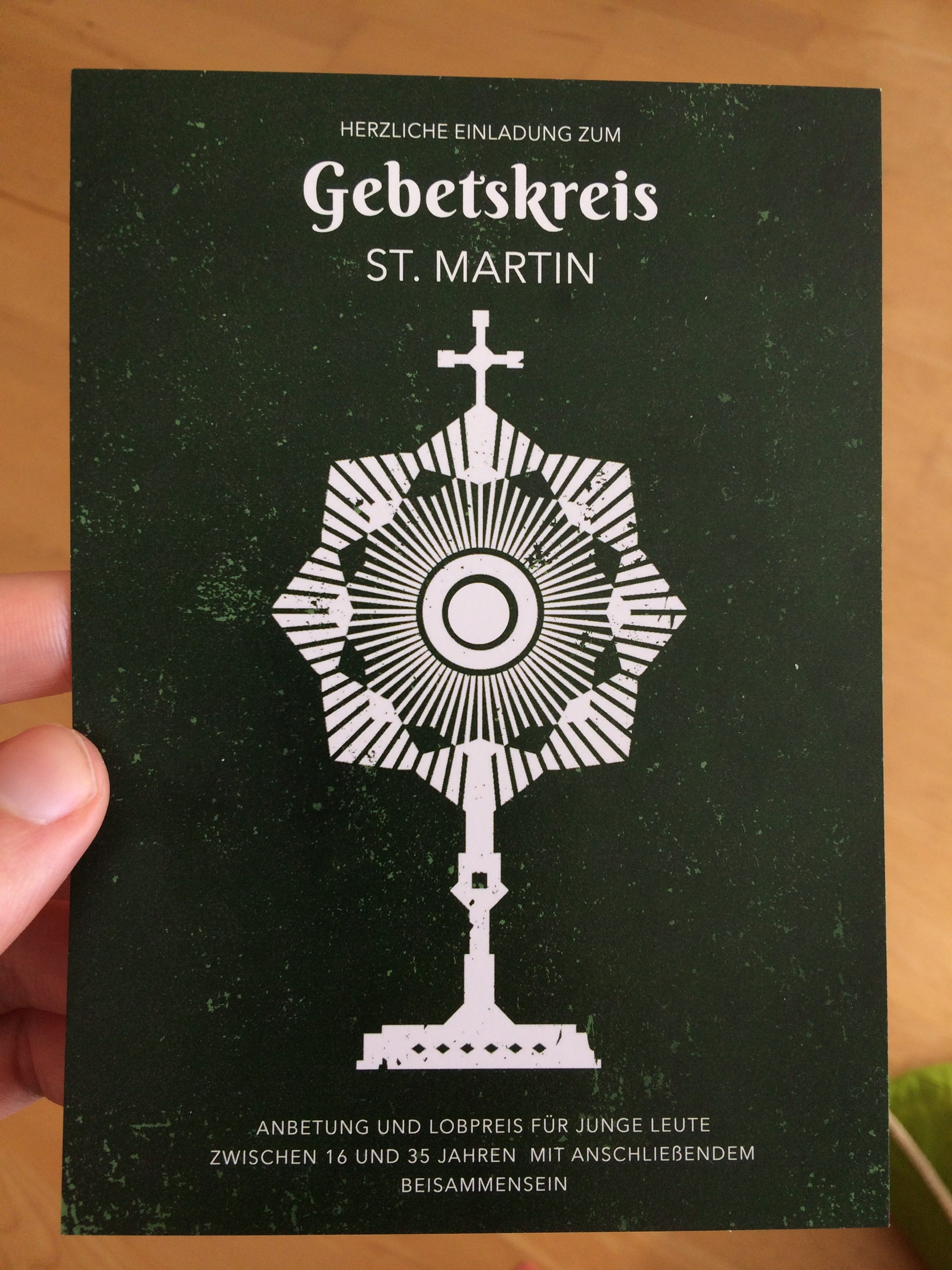

I also found a young adults prayer group that meets every other week at a church in the city center. Everyone has been really welcoming, even inviting me to other events to hang out with them. After an hour of praise & worship, we hang out with cookies and tea. It’s been a great opportunity to meet faithful young adults and practice my German, since all of them are native Germans! (And a few are now reading my blog, so shout-out to them!)

I’ve found that Germans in general tend to not approach strangers, but are really quite friendly once you approach them. For my first few weeks in Freiburg, no one talked to me after church at all (except for one fellow, who vanished quite fast once I told him I had a boyfriend). Even the clergy don’t tend to shake hands or chat after the service, and I’ve never seen an offer of donuts and coffee. I had to put in very intentional effort to involve myself, but once I did, the Germans are just as chatty, curious, and kind as Americans.

The University Church also offers a service in English once per month, but so far I’ve happened to miss it every time. Luckily, I do alright with the German services. I can understand most of what’s said now, especially since I’m already familiar with the Bible readings. Oftentimes the sermons escape me, though, because of the echo. One German tradition that I think is an interesting and nice touch is ending sermons with “Amen,” as if the sermon was one long prayer.

German ecclesial language is a little bit different and more formal than the kind of “everyday” German we learn in school, so sometimes I don’t know specific biblical or theological terms. I always find it amusing when someone refers to “Jesus and His disciples,” because in German it’s “Jesus und seine Jüngern” which sounds an awful lot like “Jesus und seine Jungen,” which means “boys”. Every time I hear a German say that, I hear it as a story about”Jesus and his ‘boyz'” getting up to some new adventure in ancient Israel. As Church history teaches us, one letter makes a world of difference.

I’m also not entirely convinced that Germans haven’t tried to make one big pun out of communion- the priest says to each person “Der Leib Christi” (the Body of Christ) before giving them the sacramental bread. However, the German word for a loaf of bread is “Laib“, which is pronounced exactly the same as “Leib” (body), and they could have very easily stuck with the word from Latin, “Körper” (like “corpus“). This coupled with the Germans’ love for puns makes me mighty suspicious.

Click on the circles below to see photo collages of some of the churches around Freiburg!

For various German Christian art, click on the circular thumbnails below: