By Cullen Smith, ’17

I believe that looking into the past gives the observer a chance to understand what was then little understood.

I believe that looking into the past gives the observer a chance to understand what was then little understood.

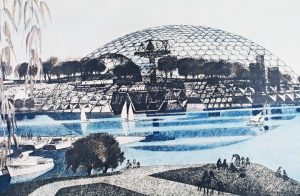

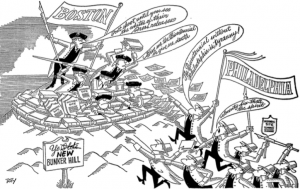

This summer, with the help of the Mellon Scholars and the History Department (and with my advisor Dr. Natalie Dykstra from the English Department), I had the opportunity to look at Expo 76, a proposal by Boston’s city planners in 1976 to create a massive “urban experiment” along the banks of Columbia Point, to celebrate the nation’s 200th birthday and the beginning of the American Revolutionary War. It would involve filling in over 400 acres of the Boston Harbor for thousands of new housing units, building a 1400-foot-long by 60-foot-high bridge across the harbor. The revenue from the Bicentennial celebration could have run past a billion dollars.

What led me to this project was an initial interest to look at Vietnam Era society on a grander scale than I had done in Holland the summer prior. By comparative means, I thought my research last summer had prepared me for looking at Vietnam Era America on a grander scale.

Because when I was knocking on the door of a Special Forces veteran in the summer of 2014 for my first Mellon Summer research project, I had little knowledge of what a veteran community looked like, and in a reciprocal sense, what that community meant to a veteran. This was especially noted when a very large German Shepard who answered only to “Fang” came to the door to greet me.

As a whole, my summer research from last year resulted in a four-part YouTube series on Dave Fetters, the Special Forces veteran I interviewed, who had served in the Vietnam War near the Cambodian border. I had utilized several software applications, mot notably iMovie and Audacity, to produce the video series. It took hours going through 6 hours of interviews, and hundreds of pictures that Dave had given me permission to use for the series.

Video production and interviewing, as it turns out, are completely separate from hardcore archival research.

Video production and interviewing, as it turns out, are completely separate from hardcore archival research.

My time in Boston, spread out from June 10th to June 24th, was an absolute whirlwind of a process, none of which involved any form of iMovie or Audacity. The best thing about Boston was that I worked in a different library every day, often doing something completely different that day than I was the last. I hopped from the Boston Public Library to Harvard’s Houghton Library to the Schlesinger Library to Northeastern Library, all within the same week. I would dig through mounds of papers related to the Boston Redevelopment Authority (Boston’s city planners), Mayor Kevin White and his personal papers, and issues of the Bicentennial Times from 9am to 5am, come home, analyze it, and then wash, rinse, and repeat.

At the same time, I was also working as a webmaster for Professor Dykstra’s Boston Summer Seminar, where teams of researchers from the intercollegiate Great Lakes College Association travel to work in various Boston archives. We would often be discussing what needed to be done with the seminar’s website, and then “switch hats” to talk about the what story I was developing with the archival materials I had found.

During my time in Boston, I was often confused as to the story I was writing. I think I found my best piece of solace when I found a 1969 letter from a middle schooler from Delaware asking about why the Bicentennial Expo was not to be held in Boston. For his conclusion: “Boston is where the fighting took place (during the Revolutionary War), so why not?”

It was from letters like this, expressing the confusion of the times and seeking simple answers, that I found my own story.

The story I wrote was partially about failure. Boston’s city planners proposed the megastructure thinking it would solve the social ills of their day, and instead received the disapproval of the entire city, especially South Boston, on the grounds that it would negatively impact the status quo.

The story I wrote was partially about failure. Boston’s city planners proposed the megastructure thinking it would solve the social ills of their day, and instead received the disapproval of the entire city, especially South Boston, on the grounds that it would negatively impact the status quo.

In another sense, however, the story that I found was about redemption. In the midst of race riots and a recession marred with massive inflation, Boston’s leadership turned the entire city into an exhibit called Boston 200. Independence Day in 1976 would see over a quarter million Bostonians flood the Charles River Esplanade to watch fireworks and activities on a perfect summer day.

With my paper and accompanying website in the final stages, there is still much of the story about Boston’s bicentennial that I have yet to fill.

What I can say thus far is that Boston has given me the chance to work with exceptional staff, live and laugh with an exceptional host family, and study in some of the nation’s top archives, all the while completing work that I (literally) spent hours dreaming about.

What I can say thus far is that Boston has given me the chance to work with exceptional staff, live and laugh with an exceptional host family, and study in some of the nation’s top archives, all the while completing work that I (literally) spent hours dreaming about.

I understood little when I came to Boston, and still recognize that my job as a historian is not done. There are always stories to tell, and the bicentennial has many more. What I can say is that as a historian, it is both a pleasure and a privilege that I am able to step outside my own existence and into someone else’s. It is only then when you can begin to understand.

Nicely done, Cullen.