The Historian’s Craft

The Historian’s Craft

Renowned French historian Marc Bloch (1886-1944) is one of the great heroes of our discipline. He revolutionized the field of history as one of the chief proponents of the Annales movement, which championed innovations in the study of history—incorporating economics, geography, and sociology; elevating ordinary lives and the mentalities and beliefs of rural society as worthy subjects of scholarship; and working from the vantage point of the long term, that is, across the centuries. More importantly for me on a personal level, he embodied the best ideals of the French republic, patriotism held in balance with universal humanistic ideals, and not a strident nationalism or narrowly exclusive nativism. A French Jew who fought valiantly in the First World War, he volunteered to fight in the Second World War at age 53. He wrote a soul-searching account of the French defeat, Strange Defeat, as the French army was retreating pell-mell in 1940. Due to his service during the First World War, the Vichy government allowed him to continue teaching despite its racial laws. When Germany moved to occupy all of France after the 1943 Allied landing in North Africa, Bloch joined the French resistance network in Lyons, was captured and tortured after about a year, and was executed along with some twenty other resistance fighters shortly after the Allied landing in Normandy and before the liberation of Paris. It was during the two years of teaching in Vichy France that he drafted The Historian’s Craft, a guide to historical methodology and a personal reflection on the value of history as an intellectual endeavor, which would remain unfinished. Both Strange Defeat and The Historian’s Craft were published posthumously. It is evident that history was integral to Bloch, to the entire person. I find it deeply moving that during the darkest hour of his country, active engagement in the exigencies of the moment did not preclude scholarship, and vice versa. If integrity means the whole person without contradictions, then Bloch is an exemplar.

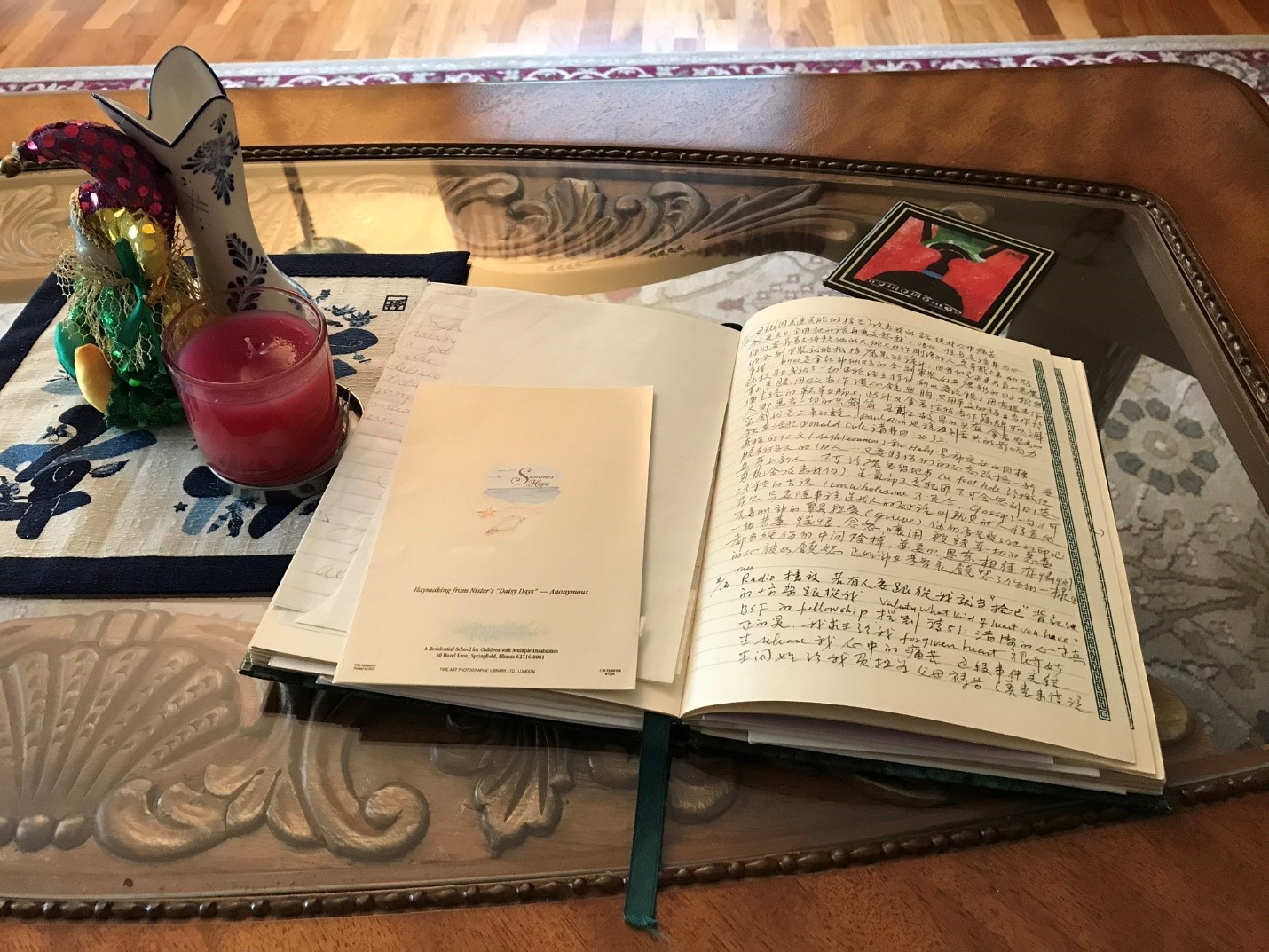

This spring a personal experience, on a much smaller scale than the world-shaking events that dictated the last five years of Bloch’s life, got me thinking about history and its place in the life of a person or family. It started with a phone call from my youngest cousin. “Hey, I’ll trade you the grading of papers for the translation of my mom’s journals,” the voice coming from the phone said. “You don’t know what you’re offering, but sure, I’d be happy to do it,” I retorted bemusedly. This cousin’s mother had passed away a few years ago, and he discovered her journals as the family was going through her affairs. “My dad said that I could keep them if I wanted; otherwise, he’s going to throw them away,” my cousin continued. “Do keep them! They’re precious!” my historian’s instinct prompted me to reply. Three months passed, and I went to Colorado Springs during spring break to keep my promise. I had a plan. We would make a catalog of the journals, twenty-four notebooks in all, during the week I was there. Afterwards, he would scan the entries that interest him most and send them to me for translation. I’d dictate; he’d type. Fancying myself in Geoffrey Reynolds’s place, I had in mind something along the lines of our Joint Archives.

As students of history invariably find out by experience, research proposals often need to be modified in the course of a project. I had several surprises once we started going through the first notebook. First, I had envisioned neat, print-like handwriting that I could skim quickly to get the gist of each journal entry. The reality was far different, and especially challenging for a non-alphabetical language such as Chinese. Second, I had approached it as a project, but it was much more personal for my cousin. I wanted to be systematic; my cousin wanted to have an entire entry translated when we came upon an entry that mentioned him or his two sisters. My “research proposal” had to be modified: we made bullet points of most entries and translated the entries for which my cousin wanted translations. In the end, we got through only one notebook. Third, I had to give up my perfectionism; finding the best expression in English for a certain Chinese term really didn’t matter as long as I got the meaning across. Fourth, and the greatest surprise, was the various effects the translation of the first notebook had on the family. A flurry of emails ensued after my cousin sent off the translation to his sisters and father. My uncle, who had wanted to throw away the journals, thanked me for my labors. Each person in the family remembered different details in the journal entries, and the same material evoked varied reactions. Should I have been surprised? Haven’t I always known that history is about people, who always have different perspectives, emotions, and responses to circumstances and events? I was humbled by the reminder that when we write history, we’re dealing with people and telling their stories. We owe it to our subjects to be truthful, not only to events and sources, but also to their perspectives. It was an “Annales” moment for me.

As students of history invariably find out by experience, research proposals often need to be modified in the course of a project. I had several surprises once we started going through the first notebook. First, I had envisioned neat, print-like handwriting that I could skim quickly to get the gist of each journal entry. The reality was far different, and especially challenging for a non-alphabetical language such as Chinese. Second, I had approached it as a project, but it was much more personal for my cousin. I wanted to be systematic; my cousin wanted to have an entire entry translated when we came upon an entry that mentioned him or his two sisters. My “research proposal” had to be modified: we made bullet points of most entries and translated the entries for which my cousin wanted translations. In the end, we got through only one notebook. Third, I had to give up my perfectionism; finding the best expression in English for a certain Chinese term really didn’t matter as long as I got the meaning across. Fourth, and the greatest surprise, was the various effects the translation of the first notebook had on the family. A flurry of emails ensued after my cousin sent off the translation to his sisters and father. My uncle, who had wanted to throw away the journals, thanked me for my labors. Each person in the family remembered different details in the journal entries, and the same material evoked varied reactions. Should I have been surprised? Haven’t I always known that history is about people, who always have different perspectives, emotions, and responses to circumstances and events? I was humbled by the reminder that when we write history, we’re dealing with people and telling their stories. We owe it to our subjects to be truthful, not only to events and sources, but also to their perspectives. It was an “Annales” moment for me.