Across the desk my adviser told me, “You will never get a history job if you don’t pursue the social studies composite major. You won’t be marketable.” I distinctly remember this conversation from my sophomore year and the frustration I felt trying to explain to the adviser that my passion is history. I saw the social studies major as a mile wide and an inch deep. If there was one thing I had learned already in my history classes at Hope College, it was that history is about depth. So instead of listening to this advice, I decided to pursue a Secondary Teaching Degree with a history major and English minor. After seven years of teaching history, I am glad I went with my instincts and pursued the history major. The skills I developed obtaining that degree have made me the teacher I am today.

Across the desk my adviser told me, “You will never get a history job if you don’t pursue the social studies composite major. You won’t be marketable.” I distinctly remember this conversation from my sophomore year and the frustration I felt trying to explain to the adviser that my passion is history. I saw the social studies major as a mile wide and an inch deep. If there was one thing I had learned already in my history classes at Hope College, it was that history is about depth. So instead of listening to this advice, I decided to pursue a Secondary Teaching Degree with a history major and English minor. After seven years of teaching history, I am glad I went with my instincts and pursued the history major. The skills I developed obtaining that degree have made me the teacher I am today.

These days, history is treated as an expendable subject in many schools. Lots of elementary schools are cutting out history lessons entirely while secondary history education classes focus on preparing students for state tests, simply filling them with facts drawn primarily from textbooks. When teachers rely on the state standards and focus on test scores, the importance of historical skills and critical thinking is lost. Studying history naturally leads students to explore different perspectives, converse with people who hold different opinions, and express their own arguments backed with relevant evidence. These were the skills I learned as a history major at Hope College, and these are the skills I try to emphasize every day as an eighth-grade history teacher.

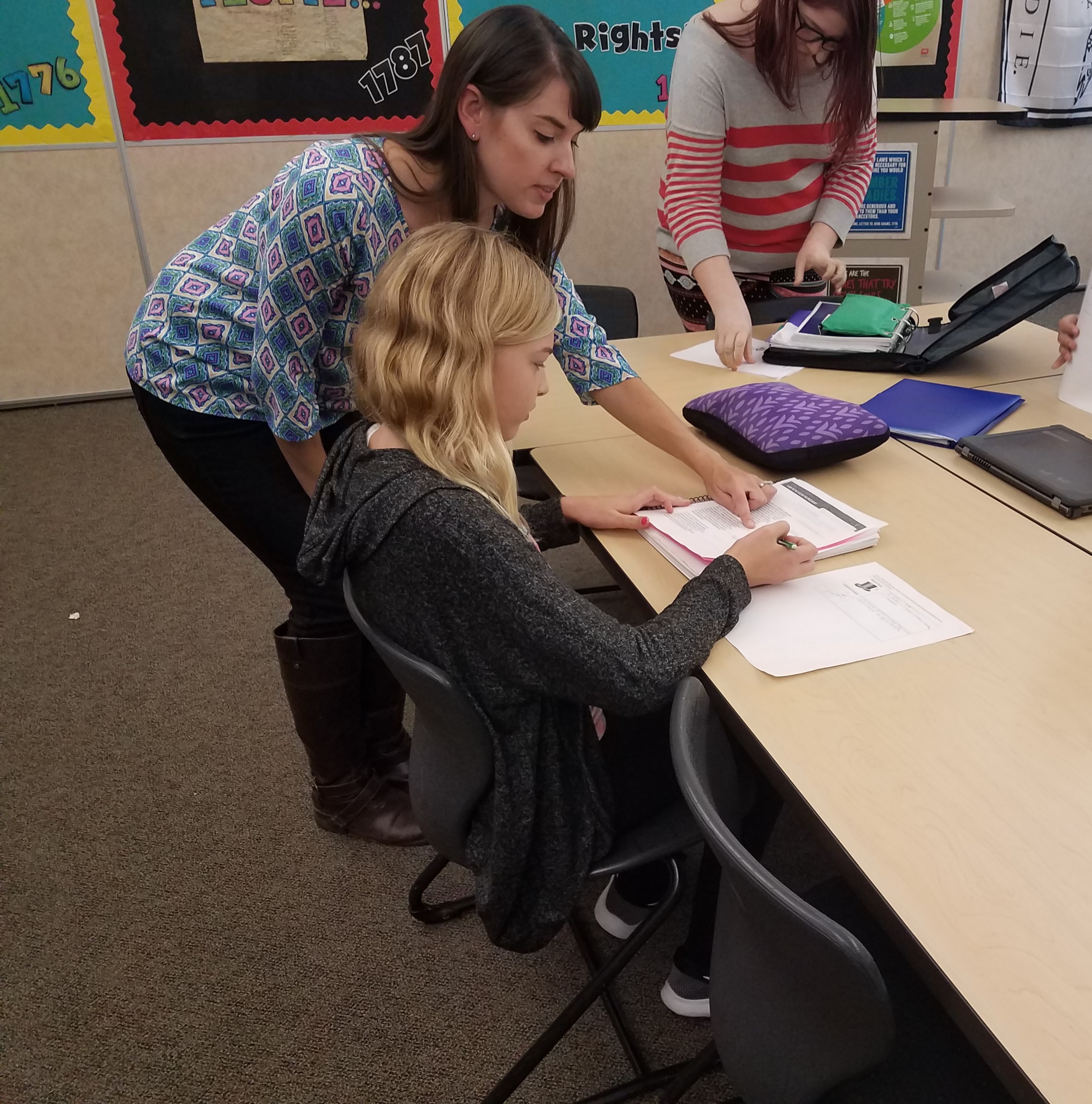

The history department at Hope was never afraid of difficult topics, but rather they embraced them, teaching us how to carefully peel back the layers and perspectives of a given event. In his British imperialism class, for example, Professor Baer would lecture about one imperialist event from multiple perspectives. This approach encouraged me to think critically about how I was previously taught about historical fact. It made me think about my own life and how I perceived events versus how others in my life may have interpreted those same events. This has carried into my classroom where I continually challenge the notion of single narratives. History is often taught in schools from one textbook—too often leaving out necessary voices to understand the complexities of events. To avoid this, I give my students contradictory primary sources on an event and ask them to determine what happened. When studying the Constitutional Convention, I have students roleplay different groups of people in America at that time. Instead of just sending upper-class men to the convention, we include African Americans, Native Americans, working-class people, and women. When we include more people from that time era, the students’ Constitution looks vastly different than the one created in 1787. This leads to great conversations about what it means when we say “we the people” or “all men are created equal.” Hope’s history department pushed me to explore what these statements meant within the context of the past, but also what they mean in the world right now. These are the same conversations I encourage with my students.

Of course, when exploring tough topics, debates often turn contentious. At Hope, my professors would encourage discussion and debate. I remember Professor Fred Johnson encouraging me to challenge his ideas and engage with him in dialogue. In our current political climate, this kind of civilized discourse is increasingly rare. Our world feels polarized and discussions often feel contentious. However, my time in the history department taught me when conflict happens, respectful conversations are important. Just as my professors taught me to present my own views, even when I didn’t agree with theirs, I encourage my students to do the same. By practicing respectful discourse and listening skills, students become capable of amazing things. I have found that through role-play discussions and debates, students are challenged to think from another’s view point—building historical empathy as well as empathy towards their peers.

My history major has pushed me to teach by emphasizing depth of learning. Instead of teaching random facts to students in the hopes that they pass a state test, I see the value in teaching historical skills and critical thinking. By treating the subject of history as an avenue to critical thinking, not only are students engaged on a personal level, but they are better prepared to participate in our world today. As citizens, we can choose to be poor historians, choosing to only listen to one side of the story and ignoring context, or we can be conscientious historians. I hope that my students chose to intentionally seek out additional points of view and engage people in difficult conversations. My students have the power to shape our country and change the world—I cannot wait to see their impact.