Why are some parts of our identity more important to us than others?

All of us have complex and multifaceted identities. Some of our identities are personal—things we like, things we’re good at (or not), distinguishing personality characteristics, etc. Some identities are social—groups that are important to us, and help us understand ourselves. Such groups can be as small as a church softball team or as large as an entire religion.

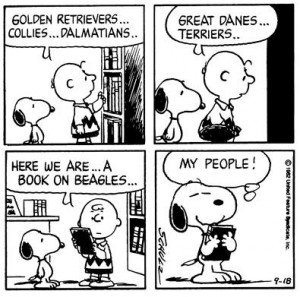

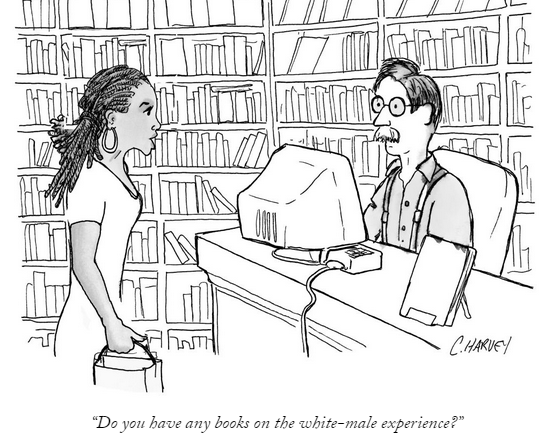

You might think we would focus on those social identities in which our group is dominant in some way. That would be more satisfying, right? As a rule, however, the opposite is true: subordinate-group identities are usually more important to us. When we’re part of a dominant group, we’re the norm. Situations, organizations, and others’ expectations have been designed to fit who we are, and we don’t have to think much about that part of ourselves.

When we’re in a subordinate group, however, things often don’t fit us so well. We are reminded regularly of how we differ from the norm. People from the dominant group generally make the decisions, often without our input. As a result, we are more aware of the ways in which our subordinate identities affect our everyday lives. That’s why—on average—LGBTQ+ people think more about their sexual orientation than straight people do, women are more likely than men think about gender, and people of color are more likely than white people to think about race.

Author and speaker Tim Wise sometimes begins a lecture by asking people how they entered the auditorium. Most folks are a little fuzzy on that—they walked in while talking with other people or thinking about other things, and they didn’t pay much attention to the route. Those who use a wheelchair, however, know exactly how they got in. Perhaps they had to enter the building at a particular door. Perhaps they had to find an out-of-the-way elevator. In many cases, they had to attend to the whole trip right up to the time they found a spot in the lecture hall. The analogy is clear: when things are designed for people like us, we don’t really notice. When we encounter barriers, however, or have to search for an alternate path, we have to pay attention. It’s much more memorable, and over time, becomes a more important part of who we are.

Author Adrian Pei (2018), an Asian American, puts all this into a very helpful context. He describes his experiences with alienation and marginalization in White contexts like this:

“It wasn’t primarily about ethnicity. It was about the realities and dynamics of what it means to be a minority amidst the majority culture. . .

It was a difference in the pain that surfaced from the unique doubts, challenges, and struggles I faced as a minority.

It was a difference in our place in this country, as majority and minorities. It was a difference in power.

It was a difference in our past. It tapped into something deep that was inside me, but was also far deeper and beyond me. My history wasn’t just about me, but about my family and the previous generations of my ethnic heritage.” (Emphases in the original.)

This is a much broader context than most majority group members usually consider. It goes beyond the one-on-one interactions that White people see. Differences in pain, in power, and in our past shape us in profound ways; when you’re in the minority, you’re much more likely to understand that than when you’re in the majority.

“[M]y body has a history that began long before me.”

—Joseph M. Pierce, In Search of an Authentic Indian: Notes on the Self

Stages of identity development

Back in the late 1960s, in the midst of a huge cultural shift in how African Americans viewed themselves and their place in U.S. society, William Cross (1971) began to study how Black Americans thought about their racial identities. (See also Vandiver et al., 2002.) His theory has been researched and modified over the years, but the gist of it is this: in a society in which you face prejudice and discrimination, it isn’t easy to develop a positive racial identity. Many people go through various stages before they have both a positive sense of themselves and a capacity for dealing productively with people from other backgrounds. Janet Helms (1995)—who directs the Institute for the Study and Promotion of Race and Culture at Boston College—has another theory of racial identity that is similar in important ways to Cross’s model, and addresses people of color generally, not just Black people.

“ERI [Ethnic-Racial Identity] is a multidimensional construct that includes several processes, including (1) efforts to understand the meaning of one’s ethnicity and race (i.e., search or exploration), (2) a strong sense of understanding and belonging to one’s ethnic–racial group or groups (i.e., commitment or resolution), and (3) positive feelings toward one’s ethnic–racial group or groups (i.e., affirmation).

Having a strong racial identity is psychologically healthy. In adults, it is modestly positively correlated with self-esteem, optimism, and ability to cope (Smith and Silva, 2011). It is similarly adaptive for adolescents (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014), and even children. Marcelo and Yates (2019) found that seven-year-old children of color with a strong sense of commitment to their racial-ethnic group were better equipped to respond to acts of dscrimination and less likely to exhibit behavior problems afterward.

I need to pause for a minute after writing that last sentence. The fact that seven-year-old children experience discrimination in this country, and have to work through the pain and the trauma that follow, makes me deeply, deeply sad. Seven. Years. Old. So many of us who are White talk about race and racism in an emotionally disconnected fashion. It’s easy for us to be patient with the lack of progress, easy to be content with our lives, easy to minimize the reality of racialization and racism. But there are seven-year-old children working through the question of what they did to deserve being mistreated. If you glided right over the last sentence of the previous paragraph, if it didn’t make you sad—and angry!—then you need to do a serious re-evaluation of the principles by which you live your life.

“Indifference to evil is more insidious that evil itself; it is more universal, more contagious, more dangerous.”

The summary that follows highlights the key points from the theories of both Helm and Cross, although as with any stage theory, this is a very broad brush. Lots of different variables come into play, and not everyone follows the same path. In addition, families, schools, churches, and other groups often guide children and adolescents through their identity development, and that support can make a big difference.

Stage One: Pre-Encounter Most children accept the world as it is, assuming that life is pretty much as it should be (excepting for things that affect them quite directly, like bedtime and broccoli). Similarly, many children of color adapt to the racism of their world; either they learn not to see it, or they justify it as reflective of their group’s inferiority. Cross calls this the pre-encounter stage because they have not yet had the kind of experience that requires them to think about what it means to be part of a subordinate group. They play down the effects of racism on themselves and others, perhaps sensing some tension, but maintaining their overall view of the world as just. Until . . .

Stage Two: Encounter . . . something happens they simply can’t deny. This could be a gradual process, or a quick reaction to a stark experience with discrimination. I had a multi-racial student a number of years ago who was raised by well-to-do White parents. She was light-skinned and smart and attractive, and didn’t think of herself as someone affected by racism. Then her White boyfriend broke up with her, out of the blue, explaining that they couldn’t get serious because he couldn’t imagine taking a Black woman home to meet his family. She was stunned, angry, and bewildered, and began thinking of herself in a whole new way, as someone who had experienced some pretty harsh racial discrimination. Like others in the encounter stage, she began asking some very important questions about what it means to be a person of color in a White-dominant society. As a result . . .

Stage Three: Immersion . . . many people who have had an encounter with racism spend a great deal of time actively exploring their racial/ethnic identity. They immerse themselves in situations that reflect their heritage. They focus on friends who share their background, swapping stories and deriving shared meaning from their experiences. They study the history and literature of their people. Explicitly and implicitly, they seek to understand what it means to be part of their social group in the context of the broader society. This is a deeply personal, often quite powerful, undertaking. Psychologist Beverly Daniel Tatum (1997) says that she attended a predominantly white university, but she spent most of her years there in the immersion stage. As a result, she barely remembers the White students she knew. It’s not that she was antagonistic toward them. It’s just that they weren’t relevant to her deep desires to figure out what it meant to her, personally and professionally, to be Black in a White society. It may take a while, but working through this Immersion stage also lays a foundation for . . .

Stage Four: Internalization . . . interacting with dominant group members in a positive, healthy manner based on mutual respect. Being more secure in one’s identity makes it easier to deal productively with people from other backgrounds, even people from the dominant group. People in this stage move pretty easily in and out of in-group and out-group settings. They know how to give—and expect—respect. They often advocate for the interests of their cultural group, and mentor younger group members who are working through questions of their own identity. It’s impressive, I think, how so many people turn experiences with racism into psychologically healthy ways of understanding themselves and working to reduce the impact of racism on others.

There are myriad variations on this theme, of course, but many people with subordinate identities follow a path similar to this. Multiracial Americans have a somewhat different set of identity questions, naturally, and you can learn a bit about that here.

I’ve written about identity development as if it happens in isolation, all by oneself. That’s not true, of course. All kinds of people are an important part of any identity development–peers, teachers, mentors, parents, family. Most parents of color do many things to help their children deal effectively with racism while maintaining a positive view of themselves and their race/ethnicity. “The talk” has become well-known in recent years, but it takes way more than one talk to raise a safe, healthy, confident child.

Clinical Psychologist Howard C. Stevenson gave a Ted Talk in which he described a talk he had with a son when he was twelve. The whole video is excellent; the part on the talk runs from 10:02 – 15:29. It’s heartbreaking, but Dr. Stevenson’s love and wisdom are, quite simply, beautiful.

Allyson Hobbs, a Stanford history professor and author of A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life (2014), summarizes the work of racial identity–of race as a verb, if you will–like this:

[Race] must be “made” from what people believe and do. Race is performative. It is the memories that bind us, the stories passed down to us, the experiences that we share, the social forces that surround us.

I can’t go without emphasize a very important point. Part of someone’s subordinate identity is fashioned in response to discrimination and contempt. But not all of it by any means. Black joy. LGBTQ+ pride. Girl power. It is especially important for those of us who are White (or straight, or male) not to fall into the trap of seeing other people only through our lens and then believing that’s how they see themselves, too. Christian Ethicist Reggie Williams (2018) says:

“To know black life, one must not only understand the struggle, one must look beyond the struggle. . . [W]e, too, are people who are made in love, and share the image of God, not only the scars of the struggle.”

Why should dominant group members know about the identity development of those in the subordinate group? Empathy. Understanding. Insight. But also because we can use that knowledge to make a positive difference. Recall Adrian Pei’s triad, above: pain, power, and the past. He says that everyone can apply this information to become more effective leaders in multiracial organizations and in the community:

Leaders who are in touch with pain . . . can see and serve people with compassion.

Leaders who are in touch with power . . . can become incredible advocates for the most vulnerable in society.

Leaders who are in touch with the past . . . can teach and guide others with great humility and wisdom. (Emphases and ellipses in the original.)

I’d like to be that kind of leader. I trust you do, too.

The Bottom Line: The development of positive subordinate identities occurs in the context of subordination. In this society, many marginalized people have to learn to reject dominant-group stereotypes and learn to appreciate the beauty in their culture and the resilience of their people. It is a powerful process that shapes how we view ourselves and others.