Do you like dogs? Do you like this dog, named Bo? What if you knew it belonged, at one time, to Barack Obama and his family? Would that matter?

Turns out that the late Sen. Ted Kennedy also had a Portuguese Water Dog, named Splash, that looked very much like Bo.

Back when Obama was still president, Political Science Professor Michael Tesler asked White Americans what they thought of the picture of Bo, telling some that he belonged to the Obama family, and telling others that he belonged to Kennedy.

Turns out that what people think about race predicts pretty well what they think about Bo. Attitudes toward Black people affected White views about Bo quite a bit. When people knew the dog belonged to the Obamas, those with positive attitudes toward Black people liked Bo a lot; those with negative attitudes toward Black people didn’t like Bo much at all. When people thought he belonged to the Kennedys, everybody thought he was all-around adorable. The effect here, quite clearly, is race, not politics. By any measure, Sen. Kennedy was more liberal (generally left-left, by U.S. standards) than Pres. Obama (center-left, by most accounts). Turns out you can like Kennedy’s dog even if you don’t like Kennedy’s politics. But if you don’t like Obama’s race? You aren’t going to his dog, either.

Pres. Obama’s race is a significant predictor of other things connected to him, too. If you want to know who opposes the idea of a national mandate to have health insurance for yourself and your family—one of the most important aspects of “Obamacare”—don’t ask people (White people, at least) their philosophy about the proper role of government in American life. That’s just a so-so predictor. Ask them what they think of Black people. That’s an excellent predictor (Tesler and Sears, 2010; Franz, Milner, and Brown, 2021).

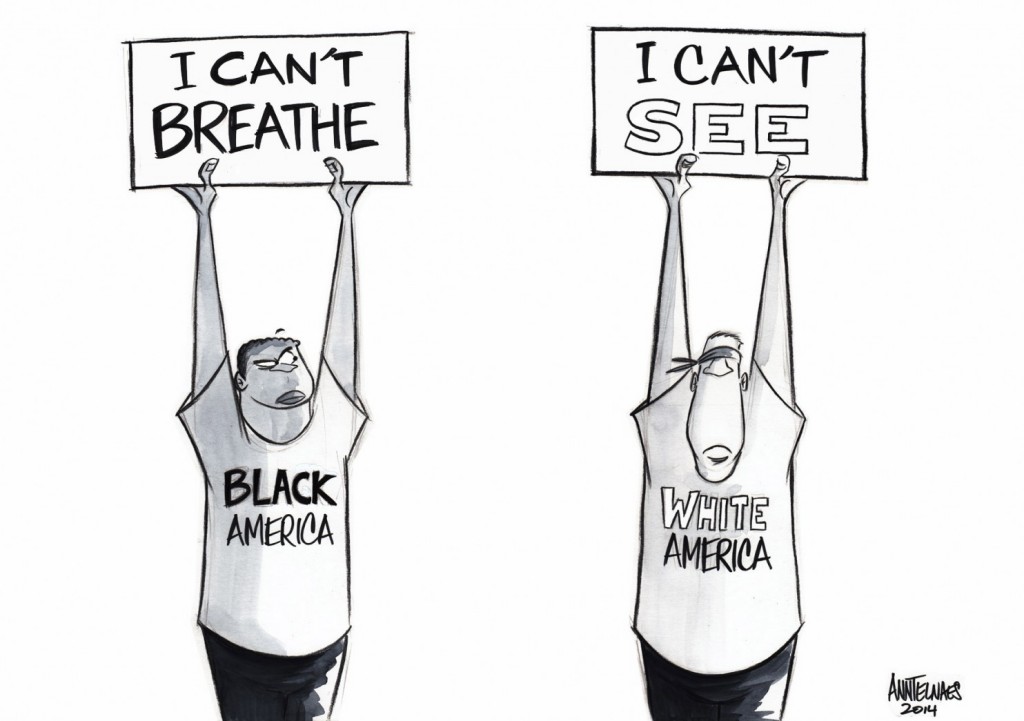

The effects of race on our attitudes are complex and, often, difficult to discern. It helps to know that there are two strong, contradictory themes in many White Americans’ statements about how race affects their lives—that race is invisible, and difficult, all at the same time.

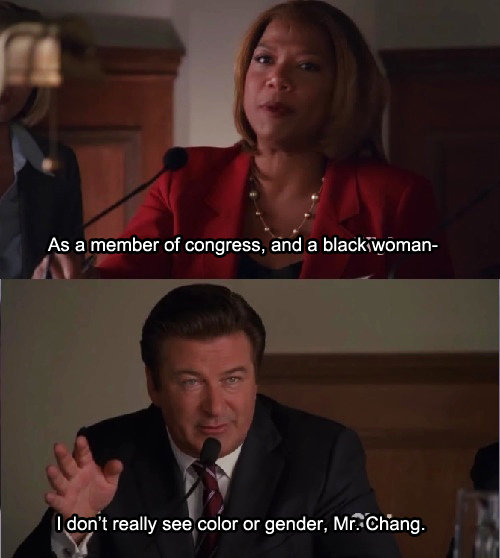

Race is invisible to me (i.e., I’m “colorblind”)

Perhaps one of the most common things you hear White Americans say about race is that they just don’t see it. It’s a simple assertion with a complicated meaning.

In part, it is a statement that many people believe signals good intentions and good will. Throughout much of our history, seeing race meant being racist, so not seeing race is intended to be a message that one is not racist. It’s a way of saying, “I know that some White people are bigots, and you may be wondering about me, too, but I’d like to assure you that I’m not.”

Asserting that one doesn’t see race makes a lot of sense, too, if you believe The Black History Month Story. Things used to be bad, but now they’re much better, and it’s such a relief that we can put all that race stuff behind us. For some, the intended function of saying we don’t see race is to declare that we are on the right side of history. It makes even more sense if one is, or would like to be, in the minimization stage of intercultural development.

But it gets complicated.

One problem with a colorblind stance is that it often co-opts the language of civil rights in order to oppose civil rights. For example, when White people quote Dr. King about judging people by the content of their character rather than the color of their skin, watch out. They often do so in order to block efforts to measure or alleviate racism. Eric Knowles and his colleagues (2009) talk about “motivated construals” of colorblindness, meaning that people use colorblind language in order to sound egalitarian when they aren’t. They found that White people who believe that it’s OK for some groups of people to have higher social standing than others (i.e., a high Social Dominance Orientation) were just as likely as egalitarian Whites to use civil-rights-type language to explain their positions. However, rather than focusing on social equality (distributive justice), they focused on making sure that individual people were treated the same way in specific instances (which is one type of procedural justice). Are people of color more likely to live in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty? Not an issue, from a Social Dominance perspective, because we shouldn’t concern ourselves with distributive justice. Equal opportunity is not the goal, and we shouldn’t attend to the race of people in different neighborhoods anyway. But are there college scholarships available only for Latinos or women or first-generation students? Now that’s a problem, because it violates a belief that race be excluded from consideration in spite of the broader social inequality that is being addressed. In the Knowles et al. study, this was especially true for those who reported feeling threatened by gains made by people of color, believing that progress made by other groups would come at the expense of White people. Very motivated construals.

Not only can a colorblind stance mask one’s prejudice, it can actually make one more prejudiced. Psychologists Jennifer Richeson and Richard Nussbaum (2004) found that White college students who read an essay espousing colorblind strategies for dealing with race (“don’t focus on race, just treat everyone as an individual”) later scored higher in implicit anti-Black prejudice than did students who read an essay espousing value-diversity strategies (“race and culture are important, and should be acknowledged along with individual characteristics”).

Holoien and Shelton (2011) asked some White university students to read an essay endorsing colorblindness; others read an essay endorsing a multicultural perspective. All students then interacted with another research participant, a person of color. Those who had just read about colorblindness were rated by independent judges as being more stand-offish and dismissive of the person of color as they spoke. Their interaction partners noticed, and were upset enough by the way they were treated to score lower on a test of cognitive depletion, the Stroop test.

“In a series of experiments, we found that when people avoided referring to race in situations that cried out for a mention of it, other people perceived them as more racially biased than if they’d brought the subject up.”

Michael Norton and Evan Apfelbaum, The Costs of Racial “Color Blindness”

Apfelbaum et al. (2010) found that upper-elementary school White students who were taught that it’s best not to notice race were less likely than students taught about valuing diversity to recognize blatant racial bigotry on the playground. They didn’t see it, or didn’t want to, and therefore were less likely to let a teacher know it was taking place.

Similarly, White adults who endorse a colorblind strategy are less likely to notice racial discrimination at work (Offermann et al., 2014), and are more likely to have negative views of a person of color who speaks up when discrimination occurs (Zou and Dickter, 2013). Tynes and Markoe (2010) found that colorblind White college students also were more accepting of race-themed parties (e.g., “gangsta” parties with White students in blackface, or “Mexican” parties with White students wearing sombreros, etc.). They often found such parties funny, in fact, laughing at the pictures and encouraging the partygoers. White students who did not endorse a colorblind view, however, strongly disapproved of race-themed parties. According to Apfelbaum, Norton, and Sommers (2012), “colorblind ideology . . . can also facilitate—and be used to justify—racial resentment.” Not noticing race = not noticing racism = disapproval of antiracism.

Perhaps that’s why White college students who have had a number of diversity experiences in college (courses, clubs, events, etc.) score lower in a measure of colorblind thinking than do students who didn’t have those experiences. The same is true for White students who report a larger number of close friendships with Black students on their campus (Neville et al., 2014). It’s not being White that’s the problem–it’s having your views about race and racism shaped by segregated White settings and perspectives. Denial doesn’t put us above racist thinking; denial puts us at the mercy of racist thinking.

Intentionally or not, a colorblind approach says, in effect, “Let’s freeze everything just as it is, with the lion’s share of resources controlled by White people. But let’s also pretend not to notice, and claim that we’re doing this in order to be non-racist.”

In their classic study of the racial attitudes of White Evangelicals (whose views are not that different from many other White people, as it turns out), Emerson and Smith (2000) have this to say about the pervasive colorblindness of their research participants:

“This is much like evangelicals of the past who, even in the face of Jim Crow segregation, did not see such segregation as the key problem. Recall that during the Jim Crow era, “Most evangelicals, even in the North, did not think it their duty to oppose segregation; it was enough to treat blacks they knew personally with courtesy and fairness.” (Martin, 1991, page 168). The racialized system itself is not directly challenged. What is challenged is the treatment of individuals within the system.”

Three real-world examples

Number One: Many people claim they cannot see the racism in such obviously racist symbols as the Confederate flag and the former mascot for the Washington, D.C. football team. “Heritage, not hate” is a false choice, obviously–given our history, the clear answer, often, is “both.” That’s why it’s so difficult to tell the difference between arguments for the Confederate flag and arguments for the Washington mascot. They are the same arguments, drawing from the same well of ideas. Click on the mascot/flag icon above to see if you can tell which arguments have been offered for the flag, and which for the mascot. See if you can do better than I did (only 5 of 16).

Number Two: In 2007, John Roberts, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, voted with the 5-4 majority to prohibit Seattle Public Schools from promoting racial integration, famously stating, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race” (Parents v. Seattle School District, 2007). Notice, however, the two different definitions of discrimination in this sentence. The first time it is used, discrimination refers to unfair actions against someone because of their race. The second time, it refers to discriminating in the sense of noticing difference, as, for example, when someone has a discriminating palate. Not noticing—or, more likely, pretending not to notice—simply hasn’t been proven an effective strategy in promoting acceptance or equality.

Seven years after the Seattle case, the Supreme Court ruled 6 – 2 that the citizens of Michigan had the right to outlaw affirmative action in a ballot initiative. The thinking again was based on the idea that a race-neutral policy is best. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, however, issued an unusually strong 58-page dissent.

Here is an edited excerpt, without her citations or parenthetical remarks:

“Race matters. Race matters in part because of the long history of racial minorities’ being denied access to the political process. Race also matters because of persistent racial inequality in society—inequality that cannot be ignored and that has produced stark socioeconomic disparities. And race matters for reasons that . . . cannot be wished away. Race matters to a young man’s view of society when he spends his teenage years watching others tense up as he passes, no matter the neighborhood where he grew up. Race matters to a young woman’s sense of self when she states her hometown, and then is pressed, “No, where are you really from?”, regardless of how many generations her family has been in the country. . . . Race matters because of the slights, the snickers, the silent judgments that reinforce that most crippling of thoughts: “I do not belong here.”

In my colleagues’ view, examining the racial impact of legislation only perpetuates racial discrimination. This refusal to accept the stark reality that race matters is regrettable. The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race, and to apply the Constitution with eyes open to the unfortunate effects of centuries of racial discrimination. As members of the judiciary tasked with intervening to carry out the guarantee of equal protection, we ought not sit back and wish away, rather than confront, the racial inequality that exists in our society. It is this view that works harm, by perpetuating the facile notion that what makes race matter is acknowledging the simple truth that race does matter.”

I wouldn’t pretend to speak to the legal issues in this or any other case. But in terms of the social science question about the merits of a color-blind vs. value-diversity approach, the evidence is clear, and it supports Justice Sotomayor.

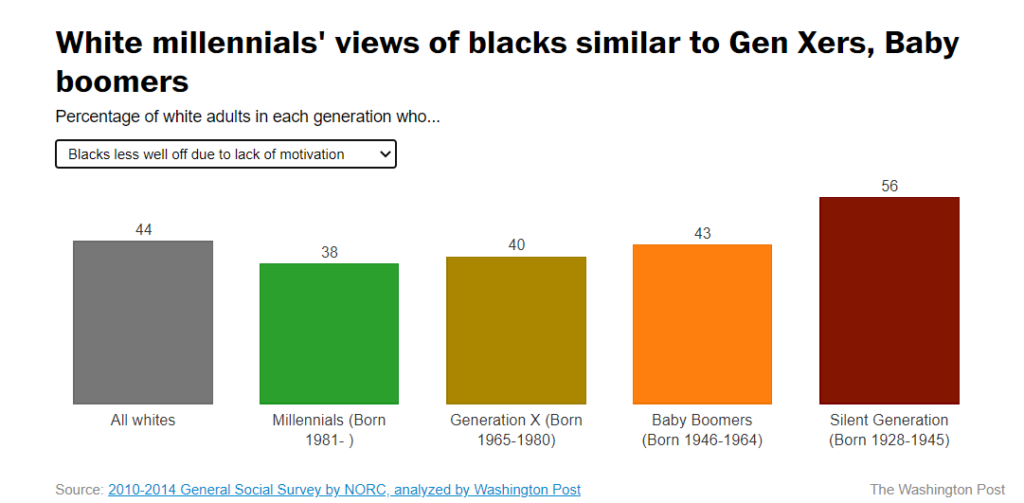

Number Three: Striving to be colorblind is a strategy for many young people, as well as older adults, as Victor Luckerson explains in this essay. Many research studies are carried out on college students, after all, who are a convenient, captive, population for researchers who work at universities, and it’s common for those studies to find a fairly large percentage of racist attitudes. You can see an example of that in this chart (click on it for the full story):

Regardless of our age, if we try to get beyond race by pretending that it has no effect, we are going to continue to be stuck where we are right now. In fact, those who say that the younger generation has moved beyond race are contributing to the colorblind fallacy, declaring victory in order to call off the effort.

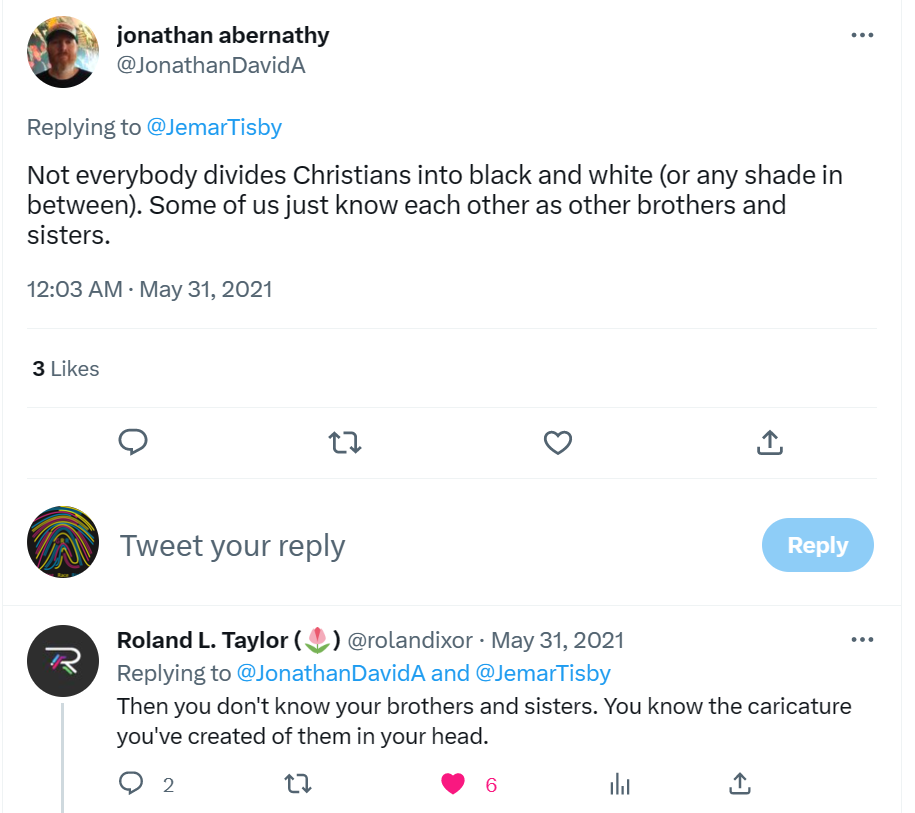

Race is difficult for me

In addition to saying they don’t see race, many White people also say that race is difficult for them, in the sense that thinking about it and talking about it with others makes them uneasy.

In my Race in America class, I ask students to write a short paper at the very beginning of the semester outlining what they know, and what they believe, about several racial issues. Most of my students of color write papers that say, in effect, “I am proud of my people, but these are the ways that race has affected me, shaped who I am, and, often, been a hardship.” Many of my White students write papers that begin with an introductory sentence very much like this: “Race is an awkward subject, one that is difficult to talk about with others.” The difference is striking: race as a life-shaping force vs. race as an occasional topic of conversation that can leave me feeling a bit anxious.

Why might White people find race a difficult topic?

For one thing, many White people don’t have much experience talking about race. People aren’t very good at most things unless they have a chance to practice.

In addition, we often have a sense that there is a lot at stake when we talk about race. The news media are full of reports of White people who said the wrong thing about race and suddenly found themselves in a heap of trouble. Or, at least, it seems sudden when we read such accounts in the news. Sometimes we worry about using the right words: I’ve been asked many times whether we are “supposed” to say Hispanic vs. Latino or Black vs. African American. Even people who haven’t thought a lot about race are aware that some words will signal that you aren’t very up on the topic. And if you aren’t very up on the topic, you might not know what words those are.

This is related to the fact that, like any other social group, White people are aware of others’ stereotypes of them. We know, or we think we know, that some people of color expect White people to be closet bigots, and we worry about accidentally fulfilling those stereotypes by doing or saying the wrong thing. The anxiety from that stereotype threat, ironically, only makes it more likely that we will fulfill the stereotype.

Samuel Gaertner and John Dovidio have done excellent, enlightening work on White anxieties about race for over forty years. They identified “aversive racism” as a common set of sometimes-conflicting attitudes and values held by many White Americans in this era of backlash to Civil Rights. Most White people want to be—and, in fact, see themselves as—racial egalitarians, open-minded people who do not have stereotypical beliefs or prejudiced attitudes, and do not engage in discriminatory behaviors.

Beneath the surface, however, many White people are aware of ways in which they fail to meet their ideals. Often they think being non-racist means they shouldn’t notice race, and they’re almost certainly failing at that. Plus, they do sometimes find themselves feeling anxious when interacting with people of color. Rather than acknowledge such difficulties, which can seem like failures, they often try to pretend those tensions don’t exist. This is aversive—that is, uncomfortable. Gaertner and Dovidio chose this term to describe their theory because of their belief that while many White people no longer feel hatred or disgust toward people of color, they do feel anxiety or discomfort toward people of different racial backgrounds. It’s different from old-fashioned racism, but it results nonetheless in some of the same outcomes.

Aversive racism is similar to the distinction between our explicit and implicit attitudes toward people of other races. Many White Americans have explicit attitudes toward people of color that are quite benign, but implicit attitudes (as measured by the speed at which they connect photos of people of different races with either positive or negative words) that are much more negative. Those implicit attitudes leak out, however, whether we want them to or not.

One of the early studies is still a classic. Back in 1977, Gaertner and Dovidio tested how often White people would come to the aid of Black people in need of help. White college students participating in an experiment “accidentally” overheard someone having an apparently-serious health problem. Would they walk down the hallway to offer assistance?

As it turned out, whether White participants were helpful depended on the race of the person in need and how many other people were present. When the research participant was the only person around who could help, s/he offered assistance to a White “victim” 81% of the time and to a Black “victim” 94% of the time. When there were two other people around, people who presumably also could help, White participants helped White “victims” 75% of the time, almost as often as when no one else was around. But when the “victim” was Black, White participants helped only 38% of the time.

When there was no one else around, White participants did the right thing regardless of the victim’s race. When they could push the responsibility onto someone else, however, they still helped White victims, but were less than half as likely to help Black victims. In other words, no racism when it might look like racism, but lots of racism when it could be explained away as something else.

Several years later, Dovidio and Gaertner (1991) asked White people to rate, on a seven-point scale, the extent to which they believed White and Black people, on average, are good and bad. (They didn’t use one scale, with good at one end and bad at the other. They used two different scales, from high to low on good and from high to low on bad.) When they asked the same people to rate both Blacks and Whites, the ratings were nearly identical. To do otherwise could have looked racist. But when people rated just one group or another, only Whites or only Blacks, there was an important difference. White people in the group rating White people and White people in the group rating Black people gave the same average rating for how bad White and Black people are. But White people in the group rating White people gave higher scores, on average, on the good scale than did White people in the group rating Black people. The White raters didn’t think that Black people are worse than Whites (measured by the ratings on the bad scale), but they did think that White people are better (measured by the ratings on the good scale).

Does this matter? Dovidio, Kawakami, and Gaertner (2002) found that when White research participants were low in explicit prejudice, and high in implicit prejudice, they said positive, friendly things to Black people in conversation (as measured by neutral observers). But their non-verbal behavior (again, measured by neutral observers) was negative, distant, even hostile. Their verbal behavior followed the explicit attitudes, but their non-verbal behavior followed their implicit attitudes. It’s easier to control what we say than it is to control how we say it.

Building on that, Richeson and Shelton (2005) filmed White people who were interacting with another White person or with a Black person. They showed clips of those films—muted, and with the other person off-screen—to both White and Black people and asked them to rate the White person in terms of words like likable, friendly, tense, and standoffish. Black raters’ judgments were significantly lower when the person in the film was interacting with a Black person, rather than a White person and the person in the film scored high in implicit prejudice. Implicit bias was clearly visible in the non-verbal behavior, and Black judges were especially adept at spotting it.

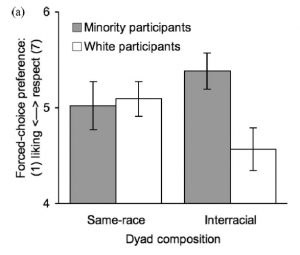

Bean et al. (2012) found that White people who are especially anxious about being perceived as prejudiced exhibited eye movements characteristic of people experiencing social threat, undermining their goal of appearing non-racist. Bergsieker, Shelton, Richeson, and Simpson (2010) studied the goals that White and Black people have in interracial interactions. They learned that White people are more eager to be liked, and Latino and Black people are more eager to be respected. My guess is that there are two reasons for this. First, White people can usually take respect for granted, while Latino and Black people cannot. Second, the stereotypes about White people have more to do with being untrustworthy and the stereotypes about Blacks and Latinos have more to do with being incompetent. Each group is hoping to overcome the stereotypes they know others have of them.

In short, race can seem difficult to grasp and to discuss because it is difficult. But many White also make it more difficult than it has to be, especially when they want to uphold White supremacy without having to accept any responsibility for doing so.

This 2015 MTV documentary on young White Americans’ views about race explores these issues further. Reality TV is not my style, but it’s worth watching.

The Bottom Line: We live in a society in which race is everywhere, but we are encouraged not to notice, and not to talk about it. White people have internalized these mixed, confusing messages—designed to preserve the racial status quo—and as a result their attitudes and feelings often are as mixed, confused, and self-serving as the society as a whole.