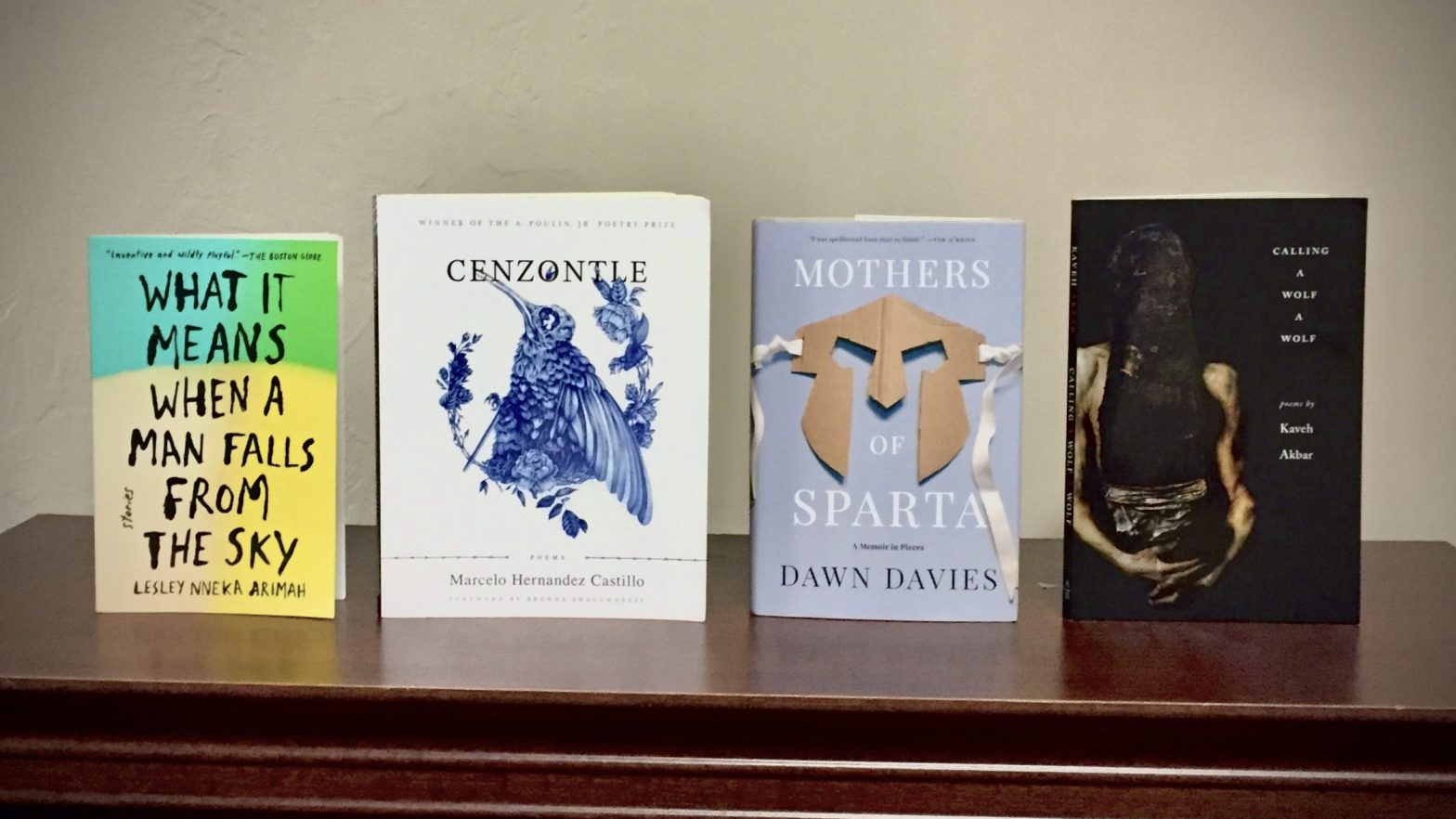

As Marcelo Hernandez Castillo dug through the photo gallery on his phone, searching for a picture of his son, I realized that the thin man who sat before me didn’t quite match my idea of the poet I had envisioned behind Cenzontle. The beautiful and surreal lyrics Castillo weaved through his 2018 book had prepared me for a somber and stoic man, with a gravity that matched the incredible weight of his poetry. I certainly hadn’t expected a man who would stop in the middle of a conversation to point out a cute baby in a stroller outside the restaurant where we shared lunch.

However, as I had more chances to speak with Castillo, I began to see where Cenzontle came from. His thoughtful nature, his appreciation of beauty: these were the traits of an author who, as Brenda Shaughnessy puts it in her foreword to Cenzontle, “knows that blood is a lyric never to be forgotten.” As Castillo spoke with our Advanced Poetry class, I saw hints of the emotional burden that drove him to produce such a powerful book of poetry; as he said, “I had to write Cenzontle so I wasn’t the sole observer—it wasn’t just mine anymore.”

Despite this, in our short time together, I couldn’t get over just how normal Castillo was. He could have been any college student, he conversed so well with my peers in class. He even shared a story of an interaction he had with another author, where they went swimming together and Castillo realized “he was just a normal guy in swim trunks.” I certainly shared this sentiment, and I wasn’t surprised to hear other students did as well; Thomas Stukey (’21) remarked: “We ask these authors what the secret is, but they’re just average people—they’re like us.”

This paradoxical image of Castillo continued throughout lunch and the Q&A session in the afternoon, where he and Lesley Nneka Arimah both displayed the warmth and humor one might expect from an old friend. Whether it was Castillo joking about how challenging he found writing, or Arimah making a witty observation about the magical realism inherent in her Evangelical upbringing, both authors handled themselves with a charming ease that felt distant from their own intense work. They even made conversations about the weather engaging, demonstrating the particular creativity that has made them such wonderful writers.

The highlight of the day, however, was the evening reading. Though I had already devoured Cenzontle, hearing Castillo read his work gave each poem a new burst of energy. Beyond that, it gave Castillo himself new life. As he read his first selection, I saw him grow into the preconceived image I had held, his stature broader, his voice larger. This was the poet I had expected: tender and powerful at once, just as his own poetry was. He also took some time to read from his recent memoir, Children of the Land, and I was struck by the equal power of his prose. Despite the different format, the energy and emotion behind the words was the same.

Arimah, too, gripped the audience as she shared two of her own short stories. Though I wasn’t familiar with her work, it didn’t take long to decide I wanted to change that. The settings and characters she laid out practically demanded that I get to know them better. Even as she immersed the audience in the dark worlds she created, though, she made sure to pull us back out in equally short order. After she finished her first story, a quick joke was all it took to break the tension in the room.

These visiting authors impact Hope College and its students in a significant way. Castillo not only offered to meet with a few students to discuss their poetry over coffee—he actively went out of his way to squeeze in meetings with as many students as he could. Even students from outside the English Department left the reading with fuller hearts; Marcus Brinks (’20), a chemical engineering major who anticipated feeling lost during the event, said afterward: “Seeing the authors read their own work was cooler than I could have ever imagined… It really enhanced the meaning for me.”

I can personally echo his thoughts: it was a delightful day with incredible authors, and I cannot wait to read the work Arimah and Castillo surely have planned for the coming years.