Online Registration for next semester starts the week of October 26, and we’ve rounded up the upper-level English course offerings that we think you’ll love!

General Education Courses

ENGL 155: Intro to Creative Writing: Poems – Susanne Davis (FA2)

Course Objective: To practice writing poems and have fun doing it! We will read poems, learn poetic techniques and put together the practice of craft with our unique expression and vision. To master one’s art requires practicing craft and analyzing how master writers practice their craft. A range of poems both classic and contemporary will help us write poems of our own. We will examine the power of image, line, speaker, diction and rhythm. Powerful art also depends, in part, on the felt experience of our humanity captured through the written word. As we develop aesthetic taste, our heart guides our responses to art. In this course we will begin to develop and hone our aesthetic taste (some of this a mysterious process at best), all toward the purpose of strengthening our own poetry. In order to succeed, this class needs for every student to possess a sincere desire to write and read, evaluate the work of others in the class and receive criticism of your own work.

ENGL 231: Literature of the Western World 1 – Stephen Hemenway (CH1, also counts for the English major)

Aesop’s fables and Homer’s tales of war and adventure start you on an odyssey of ancient literature. Frowns and smiles accompany your dramatic responses to Greek tragedies and comedies. Ancient Roman and medieval Italian epics send you on a spiritual journey that also embraces excerpts from the Hindu Bhagavad Gita and the Chinese Tao Te Ching. Chaucer takes you on a pilgrimage with the Pardoner and the Wife of Bath, and Cervantes inaugurates a quest for an impossible dream with Don Quixote. Sappho, Lady Murasaki, Margery Kempe, Marguerite de Navarre, and Sor Juana de la Cruz go places where few females dare to tread. Michelangelo, Columbus, and Shakespeare lead you through the Renaissance and Reformation and prepare you for the modern world. As you investigate and explore these authors and works, you read and take tests or written test alternatives, write journals and short papers (or a longer research project), and engage in lively discussions about these masterpieces of Western literature in a global context.

IDS 171: From Virgil to Dante – Curtis Gruenler (CH1, also counts for the English major)

During the 1500 years between the birth of Christ and the Renaissance, the world as we know it today took shape through changes such as the rise of Christianity and Islam, the invention of romantic love, the formation of modern nations, and the interaction of Christian and classical thought. Yet even though this is such a formative time for our own culture, people saw the world much differently that we do. We will try to imagine medieval life and understand medieval thought through the lenses of history, literature, philosophy, and to a lesser extent theology, music, and art. Transporting ourselves to the past can give us a new perspective on the present and on big questions like what makes a good life, what it is to love, and how people can live together well in communities and nations. This will happen most powerfully through our encounter with great texts from this time such as Virgil’s Aeneid, Augustine’s Confessions, Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, philosophical works by Plato, Aristotle, and Aquinas, the Lays of Marie de France, and above all Dante’s Divine Comedy, which we will read almost in its entirety. Students will write several short papers, one longer essay, and midterm and final exams.

IDS 172: Banned Books: From the Printing Press to the Internet – William Pannapacker (CH2)

What makes some writers so dangerous? Why would the Zeeland Public Schools get so upset about Harry Potter? Why did some readers think that The Catcher in the Ryewas a threat to American national security? Why would the Catholic Church maintain an Index of Forbidden Books for more than 400 years? Are some scientific discoveries too dangerous for the public? Why was freedom of the press a crucial part of the revolutions in England, France, and the United States? Should some books, such as Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, be banned from schools because they are too offensive? Why have banned books, such as Voltaire’s Candide and Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, become bestsellers and literary classics? Why do some people still discuss Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud in hushed tones? Why is the struggle between freedom and censorship a challenge that every generation must face? Those are some of the questions “Banned Books” will attempt to answer.

Designed for future teachers, scientists, librarians, activists, and journalists—as well as anyone who cares about the complex interplay of history, philosophy, and literature—”Banned Books” provides an overview of major events in Western Civilization during the last 500 years, from the Reformation to Globalization—while encountering a selection of banned books as a basis for more in-depth understanding of cultures to which they responded. Materials are not included in this course gratuitously; participants must risk being shocked and offended by some of the texts and images. While this course will not take place in a moral vacuum, “Banned Books” endorses no specific agenda other than the need, as mature thinkers, to balance freedom with responsibility.

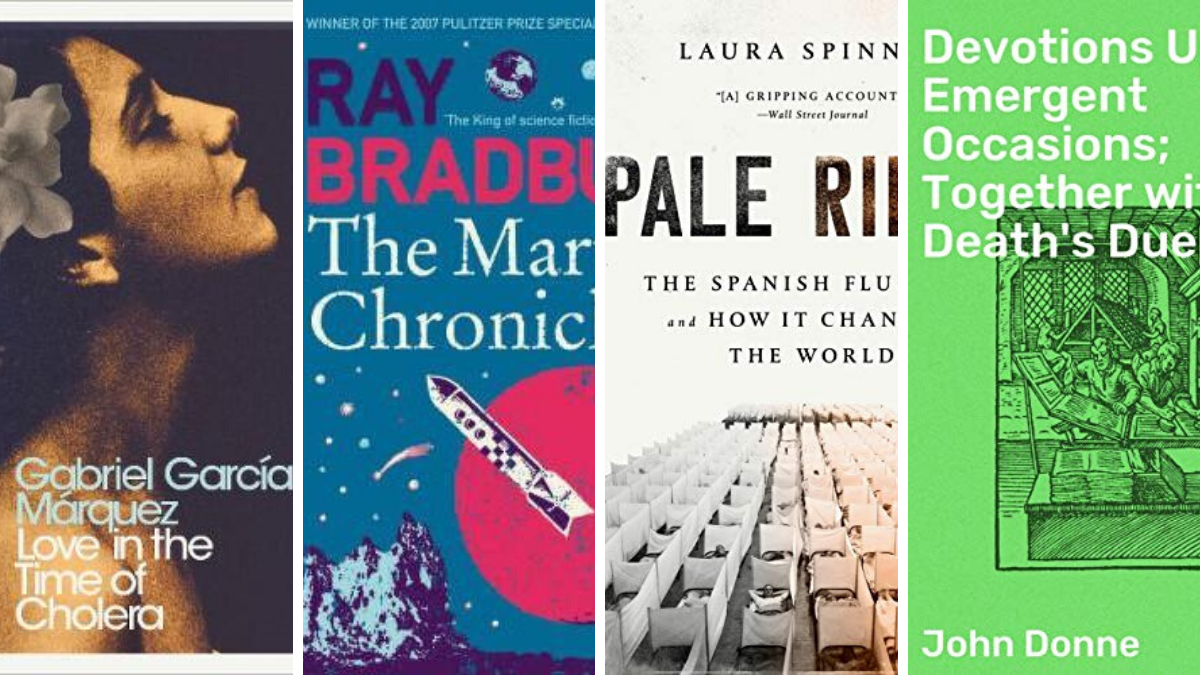

ENGL 232: Literature of the Western World II – Emily Tucker (CH2)

This course will cover Western literature from the late seventeenth century through the twenty-first century. We will read drama, novels, poetry, and short fiction in order to explore how literary works have shaped the modern’s world’s approaches to concepts like love, time, religion, science, and the pursuit of justice. We will also examine the values that have influenced the development of a canon of Western literature, as well as the efforts that have been made to challenge, critique, and expand this canon. This endeavor will take us through a number of brilliant representations of moments in Western culture: snarky cynicism among the seventeenth-century French aristocracy, clashes of sentiment and reason in early-nineteenth-century Britain, challenges to sexism and racism in twentieth-century Hollywood, and many more. Authors are likely to include Molière, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Jonathan Swift, Phyllis Wheatley, Jane Austen, Gustave Flaubert, Virginia Woolf, Gabriel García Márquez, and Lynn Nottage.

Upper-level English Courses

ENGL 248: Monsters, From Beowulf to Beloved – Jesus Montaño

What if we read Beowulf, an early medieval text written in Old English, through the lens of Toni Morrison’s Beloved, a novel about a ghost and about slavery? What would we learn about ourselves? About others?

This course is about monsters. It is a course on literature, because tales and stories are where monsters find form, where they find life. In this, monsters are bound up in our imagination, in what we find abhorrent, frightening, horrifying. And. To a large extent, what we most fear is the Other. This, then, is our task: to look at monsters through “dark” lenses that allow us see the devaluation of humanity in the making of monsters: in other words, the making of Others.

Along with Beowulf and Beloved, we will read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Octavia Butler’s Fledgling, William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and Jorge Luis Borges’s “The House of Asterion,” a short story told from the perspective of the Minotaur.

ENGL 253-02: Intro To Creative Writing – Susanne Davis

“To master one’s art requires both the practice of craft and analyzing how master writers practice their craft. In this creative writing class we will read good contemporary fiction, poetry and essays and learn to read the way writers read: to discover how the author achieves the singular effect through elements of craft. We will also learn the writing craft through images, energy, tension, pattern, insight and revision in order to write stories, poems and essays of our own. The mentioned elements are basic building blocks for the techniques in each genre. In prose, those techniques are character, plot, setting, dialogue, and point of view. In poetry we will examine the power of image, line, speaker, diction and rhythm.

My promise to you this semester: As you build your artistic expression you will capture the felt experience of humanity through your written word. As you develop aesthetic taste, your heart will guide your responses to art. In this course we will begin to develop and hone your aesthetic taste (some of this a mysterious process at best), all toward the purpose of strengthening your own writing. In order to succeed, this class needs for every student to possess a sincere desire to write and read, evaluate the work of others in the class and receive criticism of your own work.

ENGL 271 – British Literature II – Emily Tucker

This course covers British literature from the 1790s until the present, and proceeds from the understanding that Britain’s empire-building during this time produced an increasingly complex British identity. Literary works played many roles in the formation of this identity. Imperial powers used the written word to preserve traditional British culture and to promote or dispel various anxieties about Britain’s global presence. Colonial subjects fought to tell their own stories. Sometimes, readers and writers from around the world found ways to listen to each other. As the empire took shape across six continents and grew to cover a quarter of the Earth’s land surface, words built worlds, and the literatures of the British Empire developed around an increasingly diverse national identity.

The course will begin with the Romantics, whose revolutions in literary form coincided with new understandings of humanity’s relationship to nature, the divine, the past, and the international sphere. As the nineteenth century continues, we’ll trace the growth of literary realism and explore the ways in which technological developments in travel and communication generated new fascinations and fears about Britain’s role in the world. We’ll then turn to literary modernism, which developed increasing stylistic complexities as writers wrestled with the tumultuous world of the early 20th century. We’ll conclude by examining postcolonial and postmodern efforts to transform the political and artistic conventions of British literature

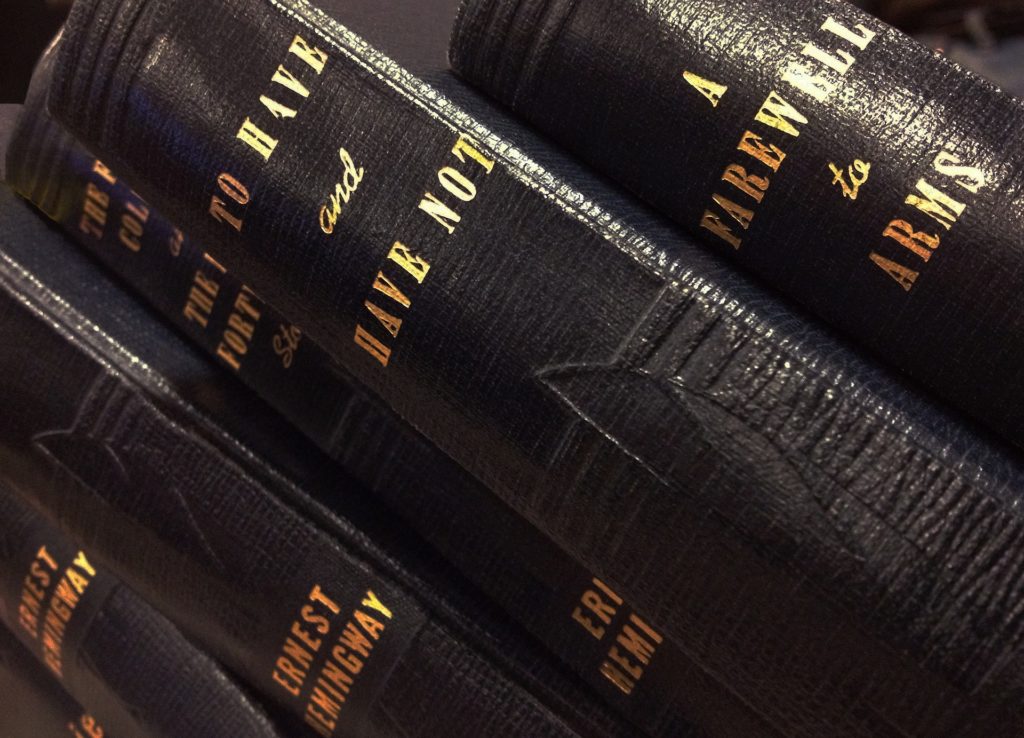

ENGL 371: Ernest Hemingway – Stephen Hemenway

For more than seven decades, people have asked me if I am the illegitimate son of Ernest Hemingway. No, I am not; we spell our names differently. However, I have come to terms with this mysterious and macho man whose complicated reputation has made his name a household word globally. Since preparing for this course four years ago, I have visited Hemingway haunts in Paris, Petoskey, Pamplona, Key West, Cuba, and Walloon Lake.

In “Ernest Hemingway: Fiction and Film,” I will present several of his short stories and novels and Hollywood versions of them to help you grapple with his “lean, hard, athletic narrative prose that puts more literary English to shame” (New York Times, 1926) and the “technicolor adaptations featuring foreign settings and doomed love, and always at least half an hour too long” (Slate, 2007).

To whom should this course appeal? All English majors will get substantive views of “Lost Generation” themes and techniques that propelled Hemingway to fame and to influencing subsequent authors. Creative Writing students will have chances to study and imitate his hard-boiled and economical realism. Secondary Education students will emerge with lesson plans for teaching such classic high-school texts as A Farewell to Arms and The Old Man and the Sea. Scientists will cherish his celebration of nature.

Women’s Studies and Psychology majors will meet “the enemy” often depicted as a multi-married misogynist. Midwesterners will love the northern Michigan settings of his Nick Adams stories. Film buffs will crave cinematic interpretations that often transformed Hemingway heroes into Hemingway clones. Travelers and adventure-seekers will want to do spring breaks in Oak Park or Mt. Kilimanjaro. I sincerely hope that Doc Hemenway on Papa Hemingway will appeal to your literary palate.

ENGL 375: Global Shakespeares – Jesus Montaño

This course is about Black Shakespeare, Latinx Shakespeare, Chilean Shakespeare, South African Shakespeare, Bollywood Shakespeare, all the Other Shakespeares. It also is about William Shakespeare. This course asks students to consider why, how, and in what ways we read Shakespeare, we perform Shakespeare, and we teach Shakespeare. This course, in this way, is about the Bard and his times, in as much as the “afterlife” of Shakespeare, that is, Shakespeare in our current moment of racial and decolonial reckoning. Therefore, alongside three Shakespeare plays, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, and Julius Caesar, the most widely taught plays in high school curricula, we will read several “companion” texts that will direct our attentions to race, ethnicity, gender, ableism, and belonging, texts such as If You Come Softly by Jacqueline Woodson, Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds, Before We Were Free by Julia Alvarez, and The Fault in Our Stars by John Green. In this course, students will be invited to engage in Global Shakespeares Studies by exploring the Shakespeare of their interest(s) in films, novels, history, and/or performances.

Students in Education, Theatre, and Communication are encouraged to join Literature and Creative Writing students in this important and dynamic class.